A young boy places a stone on the grave of his father as friends and family gather to commemorate the first anniversary of his death from heroin overdose. Between 2011 and 2021, more than 321,000 children across the U.S. lost a parent to a drug overdose, according to a recent federal study. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)

Every day, 8-year-old Emma sits in a small garden outside her grandmother’s home in Salem, Ohio, writing letters to her mom and sometimes singing songs her mother used to sing to her.

Emma’s mom, Danielle Stanley, died of an overdose last year. She was 34, and had struggled with addiction since she was a teenager, said Brenda “Nina” Hamilton, Danielle’s mother and Emma’s grandmother.

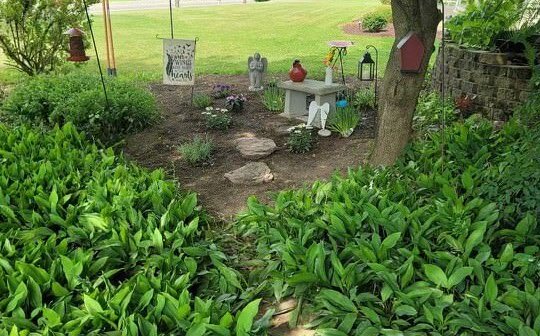

“We built a memorial for Emma so that she could visit her mom, and she’ll go out and talk to her, tell her about her day,” Hamilton said.

Lush with hibiscus and sunflowers, lavender and a plum tree, the space is a small oasis where she also can “cry and be angry,” Emma told Stateline.

Hundreds of thousands of other kids are in a similar situation: More than 321,000 children in the U.S. lost a parent to a drug overdose in the decade between 2011 and 2021, according to a study by federal health researchers that was published in JAMA Psychiatry in May.

In recent years, opioid manufacturers, distributors and retailers have paid states billions of dollars to settle lawsuits accusing them of contributing to the overdose epidemic. Some experts and advocates want states to use some of that money to help these children cope with the loss of their parents. Others want more support for caregivers, and special mental health programs to help the kids work through their long-term trauma — and to break a pattern of addiction that often cycles through generations.

The rate of children who lost parents to drug overdoses more than doubled during the decade included in the study, surging from 27 kids per 100,000 in 2011 to 63 per 100,000 in 2021.

Nearly three-quarters of the 649,599 adults between ages 18 and 64 who died during that period were white.

The children of American Indians and Alaska Natives lost a parent at a rate of 187 per 100,000, more than double the rate among the children of non-Hispanic white parents and Black parents (76.5 and 73.2 per 100,000, respectively). Children of young Black parents between ages 18 and 25 saw the greatest loss increase per year, according to the researchers, at a rate of almost 24%. The study did not include overdose victims who were homeless, incarcerated or living in institutions.

The data included deaths from illicit drugs, such as cocaine, heroin or hallucinogens; prescription opioids, including pain relievers; and stimulants, sedatives and tranquilizers. Danielle Stanley, Emma’s mother, had a combination of drugs in her system when she died.

At-risk children

Children need help to get through their immediate grief, but they also need longer-term support, said Chad Shearer, senior vice president for policy at the United Hospital Fund of New York and former deputy director at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s State Health Reform Assistance Network.

An estimated 2.2 million U.S. children were affected by the opioid epidemic in 2017, according to the hospital fund, meaning they were living with a parent with opioid use disorder, were in foster care because of a parent’s opioid use, or had a parent incarcerated due to opioids.

“This is a uniquely at-risk subpopulation of children, and they need kind of coordinated and ongoing services and support that takes into account: What does the remaining family actually look like, and what are the supports that those kids do or don’t have access to?” Shearer said.

Ron Browder, president of the Ohio Federation for Health Equity and Social Justice, an advocacy group, said “respecting the cultural traditions of families” is essential to supporting them effectively. The state has one of the 10 highest overdose death rates in the nation and the fifth-highest number of deaths, according to 2022 data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For second year in a row, Kentucky overdose deaths decrease?

The goal, Browder said, should be to keep kids in the care of a family member whenever possible.

“We just want to make sure children are not sitting somewhere in a strange room,” said Browder, the former chief for child and adult protection, adoption and kinship at the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services and executive director of the Children’s Defense Fund of Ohio.

“The child has gone through trauma from losing their parent to the overdose, and now you put them in a stranger’s home, and then you retraumatize them.”

This is a particular concern for Indigenous children, who have suffered disproportionate removal from their families and forced cultural assimilation over generations.

“What hits me and hurts my heart the most is that we have another generation of children that potentially are not going to be connected to their culture,” said Danica Love Brown, a behavioral health specialist and member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Brown is vice president of behavioral health transformation at Kauffman and Associates, a national tribal health consulting firm.

“We do know that culture is healing, and when people are connected to their culture … when they’re connected to their land and their community, they’re connected to their cultural activities, the healthier they are,” she said.

Ana Beltran, an attorney at Generations United, which supports kin caregivers and grandfamilies, said large families still often need money and counseling to take care of orphaned children. (UNICEF defines an orphan as a child who has lost at least one parent.) She noted that multigenerational households are common in Black, Latino and Indigenous families.

“It can look like they have a lot of support because they have these huge networks, and that’s such a powerful component of their culture and such a cultural strength. But on the other hand, service providers shouldn’t just walk away because, ‘Oh, they’re good,’” she said.

Counties with higher overdose death rates were more likely to have children with grandparents as the primary caregiver, according to a 2023 study from East Tennessee State University. This was particularly true for counties across states in the Appalachian region. Tennessee has the third-highest drug overdose death rate in the nation, following the District of Columbia and West Virginia.

‘Get well’

AmandaLynn Reese, chief program officer at Harm Reduction Ohio, a nonprofit that distributes kits of the opioid-overdose antidote naloxone, lost her parents to the drug epidemic and struggled with addiction herself.

Her mother died from an overdose 10 years ago, when Reese was in her mid-20s, and she lost her dad when she was 8. Her mom was a waitress and cleaned houses, and her dad was an autoworker. Both struggled with prescription opioids, specifically painkillers, as well as illicit drugs.

“Maybe we couldn’t save our mama, but, you know, somebody else’s mama is out there,” Reese said. “Children of loss are left out of the conversation. … This is bigger than the way we were seeing it, and it has long-lasting effects.”

In Ohio, Emma’s grandmother started a small shop called Nina’s Closet, where caregivers or those battling addiction can come by and collect clothing donations and naloxone.

Emma, who helps fill donation boxes, tells her grandmother she misses the scent of her mom’s hair. She couldn’t describe it, Hamilton said — just that “it had a special smell.”

And in an interview with Stateline, Emma said she wants kids like her to have hobbies — “something they really, really like to do” — to distract them from the sadness.

She likes to think of her mom as smiling, remembering how fun she was and how she liked to play pranks on Emma’s grandfather.

“This is what I would say to the users: ‘Get treatment, get well,’” Emma said.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: [email protected]. Follow Stateline on Facebook and X.

]]>Franklin County Court House (Kentucky Lantern photo by Sarah Ladd)

Franklin Circuit Court Judge Thomas Wingate has dismissed a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of a 2024 law banning the sale of some vaping products.?

In doing so, Wingate sided with the lawsuit’s defendants — Allyson Taylor, commissioner of the Kentucky Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control, and Secretary of State Michael Adams — who filed a motion to dismiss.?

Greg Troutman, a lawyer for the Kentucky Smoke Free Association, which represents vape retailers, had argued that the law was too broad and arbitrary to pass constitutional muster because it is titled “AN ACT relating to nicotine products” but also discusses “other substances.” The state constitution says a law cannot relate to more than one subject.?

In his opinion, Wingate said the law doesn’t violate the state constitution.?

The law’s title “more than furnishes a clue to its contents and provides a general idea of the bill’s contents,” he wrote.?

The law’s “reference to ‘other substances’ is not used in a manner outside of the context of the bill, but rather to logically indicate what is unauthorized,” Wingate wrote.?

The lawsuit centers around House Bill 11, which passed during the 2024 legislative session and goes into effect Jan. 1. Backers of the legislation said it’s a way to curb underage vaping by limiting sales to “authorized products” or those that have “a safe harbor certification” based on their status with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).?

Opponents have said it will hurt small businesses, lead to a monopoly for big retailers and could drive youth to traditional cigarettes.?

Altria, the parent company of tobacco giant Phillip Morris, lobbied for the Kentucky bill, according to Legislative Ethics Commission records. Based in Richmond, Virginia, the company is pushing similar bills in other states. Altria, which has moved aggressively into e-cigarette sales, markets multiple vaping products that have FDA approval.

“The sale of nicotine and vapor products are highly regulated in every state, and the court will not question the specific reasons for the General Assembly’s decision to regulate and limit the sale of? nicotine and vapor products to only products approved by the FDA or granted a safe-harbor certification by the FDA,” Wingate wrote in a Monday opinion. “The regulation of these products directly relates to the health and safety of the Commonwealth’s citizens, the power of which is vested by the Kentucky? Constitution in the General Assembly.”??

Kentucky Attorney General Russell Coleman, as well as Taylor and Adams, praised the ruling in their favor.

Coleman said the ruling “underscores” that the “General Assembly is empowered to make laws protecting Kentuckians’ health and charting our course for a bright future.”

“The Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control appreciated the clarity gained from the Courts that this law is constitutional,” Taylor, the commissioner, said in a statement. “ABC will continue with its implementation efforts and will be prepared to enforce the law when it takes effect in January.”

Rep. Rebecca Raymer, R-Morgantown, who sponsored the bill, said she’s “pleased to see the Court rule in favor of our efforts to ensure the health and safety of Kentuckians. As a lawmaker, mother and health care provider, I believe we owe it to the people of this state, particularly our children, to ensure that the products they are using are safe.”

“If a product can’t get authorized or doesn’t fall under the FDA’s safe harbor rules, we don’t know if the ingredients are safe, where they’re from, or what impact they will have on a user’s health,” Raymer said in a statement.

Sen. Brandon Storm, R-London, who carried the bill in the Senate, echoed Raymer.

“Judge Wingate made the correct ruling and did well in articulating that HB 11 and other bills focused on oversight of products to safeguard the health and safety of Kentucky residents is a constitutional responsibility entrusted to the Kentucky General Assembly,” he said. “As lawmakers, we have a great responsibility to steer public policy in a direction that better protects the public, especially when it involves negative health consequences for Kentucky children. I’m pleased HB 11 will stand and look forward to working with my colleagues further to protect the health and well-being of our constituents.”

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Kentucky has the nation's highest rate of lung cancer incidence and death. Nearly 9 out of 10 lung cancer deaths are caused by smoking cigarettes or secondhand smoke exposure, says the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (Getty Images)

Increasing state cigarette taxes has proven to be an effective policy to decrease smoking rates, and it appears that is also true in Kentucky.

Nearly 30 percent of Kentucky adults smoked in 2011, two years after the legislature had doubled the cigarette tax to 60 cents a pack. Following a 50-cent increase to $1.10 in 2018, the state’s adult smoking rate fell to 17.4% in 2022, the last year for which a rate is available.

Shannon Baker, the American Lung Association’s advocacy director for Kentucky and Tennessee, said that while she could not point to something definitive to explain why Kentucky’s smoking rate has been decreasing, as has also been the case in the nation, she could speak to the impact of raising cigarette taxes:

“When taxes increase, smoking rates decline. We should take advantage of that, for goodness sake, and increase the cigarette tax in Kentucky by at least $1 and then tax all other nicotine products at parity with the cigarette tax.”

After the initial boost in cigarette-tax revenue from the rate hikes in 2011 and 2018, revenue from the tax declined 24% from 2019 to 2024.

The legislature increased the tax to 30 cents from 3 cents in 2005, but smoking rates before 2011 should not be compared with those after that because of a change in survey methodology, says the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a continuing federal-state poll of Americans’ habits.

Baker stressed that its important to take advantage of all policies that are known to decrease smoking. Beyond raising taxes, she said it’s important to fund the state tobacco-control program and enforce the law against underage sales, which she said would result in fewer youth becoming addicted to nicotine and growing up to be lifelong smokers, and all the health issues that come with that.

The new report on state General Fund receipts for the fiscal year that ended June 30 showed a 1.5% increase in receipts from other tobacco products, such as electronic cigarettes or vapes.

Asked about the impact of vaping on decreasing smoking rates, Baker focused her comments on young people, who are more likely to vape than smoke.

“We really have to get a handle on this youth vaping problem,” she said, noting that Kentucky is one of about 10 states that doesn’t require tobacco retailers to be licensed. “We don’t even know where all of these shops are in order to enforce the law against underage sales.”

Baker added, “We really need a better method of enforcing the law against underage sales. And what that looks like is licensure and routine regular enforcement opportunities that result in significant penalties all the way up to license suspension and revocation, for scofflaws that routinely violate the law. We’re not talking about any onerous policy on those who are compliant with the law. We’re simply talking about those who violate the law and violate it routinely.”

The 2023 Youth Risk Behavior Survey found that 5.3% of Kentucky high school students said they currently smoked cigarettes and 19.7% said they used electronic vapor products. Among middle schoolers, 2.2% said they smoked cigarettes and 12.8% used a vapor product. “Current use” is considered having used a product on at least one day during the 30 days prior to the survey.

Asked if she thought the new law that bans retailers from selling unauthorized vapor products would be effective in decreasing youth vaping, as it has been touted to do, Baker said, “House Bill 11 turned into . . . an industry market-share grab and nothing more; it is not a protection for kids. What we saw was a bill passing that, in effect would, if it’s upheld in court, remove certain products, primarily imported products, from the market shelves, which in and of itself is not a bad thing. But, it certainly doesn’t protect kids who will just switch to the other products that remain on the shelves.”

The law has been challenged in court. If it holds up, it will go into effect in January 2025.

Baker also wanted to make sure people know that the funds for the state’s tobacco control program come from the Master Settlement Agreement with cigarette manufacturers, not from the cigarette tax.

“We need to increase funding for tobacco control because … Kentucky has the highest lung-cancer incidence and mortality rates in the entire nation and most of that is due to our high smoking rate,” Baler said. “So even though the smoking rate may be declining, it isn’t gone. It isn’t good, even.”

This story is republished by Kentucky Health News

]]>Sen. Danny Carroll's bill seeks to address problems in Kentucky's juvenile detention system. (Photo by Getty Images)

FRANKFORT — A review of Kentucky’s Department of Juvenile Justice found “??disorganization across facilities” and a “lack of leadership from the Beshear Administration,” Republican Auditor Allison Ball said Wednesday.

However, an administration spokesperson said neither the Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) nor the Justice and Public Safety Cabinet was given the opportunity to review the audit findings or respond before it was published.

The audit, released Wednesday, began under the previous auditor, Republican Mike Harmon. Concerns in the department have been raised by Republicans in Frankfort after reports of violence and understaffing in the juvenile justice system have made headlines.?

CGL Management Group was contracted by the auditor’s office to review the department. The report’s executive summary highlighted juvenile detention facilities are “significantly understaffed,” leading to “high levels of overtime” that “negatively impact recruitment and retention.” It also found the Detention Division of DJJ “lacks a unified strategic direction,” as facilities and major departments are operating in “silos” and “conflicting communication” led to confusion “regarding its detention mission.”?

Ball said in a statement that she was “alarmed” by the report’s findings, but remained “hopeful this will provide clear direction for the numerous improvements needed within our juvenile justice system and open the door for accountability and action within DJJ.”

“The state of the Department of Juvenile Justice has been a concern across the Commonwealth and a legislative priority over the past several years,” Ball said. “The findings from this review demonstrate a lack of leadership from the Beshear Administration which has led to disorganization across facilities, and as a result, the unacceptably poor treatment of Kentucky youth.”

Justice and Public Safety Cabinet Communications Director Morgan Hall said in a statement that the auditor’s office did not provide DJJ or the cabinet with a copy of the audit until late Wednesday morning.

“Unlike the previous administration, we’ve started making sweeping improvements to the juvenile justice system, including making it a priority to protect staff and juveniles and create secure facilities by increasing staffing levels,” Hall said.

She referred to steps the Beshear administration has taken to reclassify youth workers as correctional officers and raising the starting salary of youth workers in detention centers to $50,000 annually. Hall said “great strides” had been made in hiring at facilities in Fayette, Boyd and Breathitt counties, making those facilities almost fully staffed.

“In the past year, as a result of the administration’s efforts, we have increased frontline correctional officers by 63%,” Hall said. She said that’s the “highest number DJJ has employed in recent history, and we are continuing to recruit and retain to further secure our facilities.”

Joy Markland, communications director for the auditor’s office, said in response that the office sent the report to the cabinet secretary and DJJ commissioner “as a courtesy” because it was not required by law. Legislation passed last session, which was signed by Beshear required the report be provided to the Legislative Research Commission once completed.

“It is disingenuous for the Beshear administration to complain about not being given advance notice of these findings when many of the issues are essentially the same as those from a previously conducted audit performed by the Center for Children’s Law and Policy in 2017,” Markland added.

The report’s executive summary also found:?

- Department isolation policies and practices “are inconsistently defined, applied, and in conflict with nationally recognized best practices.”?

- The department’s use of force practices do not align with common juvenile detention practices and “are poorly deployed and defined.” Chemical agents, tasers and other security control devices were introduced “without a policy in place.”?

- The department does not have a “clear, evidence-based behavior management model” to manage youth in detention.?

- The review firm found medical and mental records showed direct services provided to youth patients met expected standards, but “there was a lack of appropriate documentation in many of the files.” Additionally, on-site reviews of mental and physical health services showed “chronic staffing challenges, poor workload balancing, lack of consistent operational practices, and inefficiencies associated with the use of a problematic medical record system” created an environment that could not accommodate challenges in delivering health care.?

- Moving from a regional detention model created “continuity of care issues” for the population in DJJ.?

- Staff training mirrors national standards, but the implementation is “ineffective.”?

- The department policy manual does not have “clarity and consistency,” which can lead to “misunderstanding and may negatively impact agency performance and operations.”?

- The department does not have an “effective quality assurance program” to support its mission and meet expectations.?

- The department’s youth information management systems had “limited functionality and inadequate reporting capabilities.” This affected DJJ’s access to performance metrics and understanding of operations.?

- The department has not operationalized findings from a 2017 report from the Center for Children’s Law and Poverty.?

Calls for change

Last year, Republican lawmakers called on the auditor’s office to lead a full performance audit. Beshear welcomed the audit if it was conducted in a non-political way.?

GOP legislators have been critical of Secretary of the Justice and Public Safety Cabinet Kerry Harvey and former Department of Juvenile Justice Commissioner Vicki Reed. Harvey is set to retire Thursday and Reed left the department earlier this month. Both were appointed by Beshear in August 2021.??

Ahead of the 2023 legislative session, reports of violence in Kentucky’s juvenile justice system regularly made headlines, including a riot in Adair County during which a girl in state custody was allegedly sexually assaulted and employees were attacked at a youth detention center in Warren County. DJJ has also faced persistent staffing issues.?

Senate President Pro Tem David Givens, R-??Greensburg, said in a Wednesday statement lawmakers have read previous reports that “uncovered tragic situations surrounding Kentucky youth and staff in state facilities” and have heard directly from whistleblowers who have “long known there has been an absence of leadership in the executive branch in this arena. ” Givens sponsored legislation last session calling for an independent audit of DJJ.

“We remain resolved to help fill that void because, in the absence of leadership, a problem sadly became a crisis,” Givens said. “I look forward to analyzing the auditor’s report for a better understanding of the depth of the crisis.”

Senate Majority Caucus Chair Julie Raque Adams, of Louisville, also criticized the Beshear administration, saying “Kentucky’s most vulnerable children deserve better” and added the system does not have “any real leadership strategic direction to finding a solution.”

Sen. Danny Carroll, R-Benton, who co-chaired a workgroup that focused on juvenile justice last year, said information in Wednesday’s report will be helpful as lawmakers continue to focus on juvenile justice challenges. He remiained “optimistic about the conversations and collaborative efforts I am having with those within DJJ, the Kentucky Justice Cabinet and the Cabinet for Health and Family Services.”

Beshear signed two bipartisan bills into law aimed at improving the juvenile justice system. One allocated $20 million to renovate and operate a youth detention center in Jefferson County and the other provided more than $50 million for salaries, retention, new workers and security upgrades, including $30 million for workers in the adult corrections system.?

The governor previously announced several changes to the department, including establishing a female-only juvenile facility in Campbell County, separating male juveniles by level of offense, expanding the department’s transportation branch, raising salaries and more.?

Hall provided a copy of a seven-page policy to allow defensive equipment, including pepper spray and tasers, in the department that went into effect earlier this month. Reed had given approval.

“Prior to deployment of the equipment, standard operating procedures had been implemented and all staff had been trained,” Hall added.

Editor’s note: This story was updated with additional comments.?

]]>Sen. Stephen Meredith, R-Leitchfield, pictured at the Legislature on Jan. 10. Meredith is sponsoring Senate Bill 93 which aims to prevent education funding from going to diversity, equity and inclusion in K-12 schools. (LRC Public Information)

FRANKFORT — A bill aimed at preventing education funding to go to diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging frameworks in K-12 schools would also remove language protecting “trauma-informed” methods in Kentucky schools if the bill remains unchanged as it makes its way through the General Assembly.?

Part of recently-filed Senate Bill 93 from Sen. Stephen Meredith, R-Leitchfield, would remove language around the approach that places an emphasis on supporting all students, regardless of their experiences, if enacted. However, some advocates say such language added to state law with bipartisan support in 2019 fosters a welcoming and supportive environment for Kentucky students.?

A guide from the Kentucky Department of Education defines a trauma-informed school as “one in which all students feel safe, welcomed and supported, and where addressing trauma’s impact on learning on a schoolwide basis is at the center of its educational mission.”?

Meredith told reporters on Wednesday that trauma-informed approaches in state law could give a backdoor way to support a “DEI agenda,” and he feels the original language could be enhanced for more parental involvement. The bill was assigned to the Senate Education Committee on Thursday.?

“If you look at the original legislation where you’re building these groups to take care of kids in trauma, what’s conspicuously missing from that? Parents,” the senator said. “There’s no parental involvement at all. That should be a key part of this entire process.”?

But the Kentucky Student Voice Team, a policy advocate organization, voiced opposition to SB 93 for “a multitude of reasons,” including the elimination of trauma-informed care in schools. In a statement to the Kentucky Lantern, KSVT said trauma-informed care helps people navigate the impacts of dangerous experiences and such approaches are “recommended in schools by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration ‘to foster a safe, stable, and understanding learning environment for all students and staff.’?

“Couldn’t it be said with the utmost certainty that all parents and students want a safe, stable, learning environment?” KSVT said. “As an organization that values research and advocates for high quality education for all, we find the legislative attempt to strike an evidence-based approach to supporting the mental health of young people problematic.”

Brent McKim, the president of the Jefferson County Teachers Association, said in an email that education research has made “it very clear that legislation like SB 93 would absolutely prevent schools from creating the sort of safe and welcoming learning conditions necessary for students to succeed.”?

“As teachers, we have chosen education as a career because we want to help every student achieve their dreams, and this is not possible if the state makes it against the law to have welcoming classrooms where they feel safe and have a sense of belonging,” McKim said.?

How ‘trauma-informed approaches’ made it into state law

Trauma-informed approaches were a key part of the School Safety and Resiliency Act, which the General Assembly passed in 2019. The law was in response to a school shooting at Marshall County High School, in which two students were killed and more than a dozen injured. The Republican-backed measure received bipartisan support — including a signature from Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear.?

The primary sponsor of the school safety act, Sen. Max Wise, R-Campbellsville, said on Thursday that he had not read the entirety of Meredith’s bill, but was aware of the provision that would remove trauma-informed language from statute. He added that he hoped Meredith would get feedback from school superintendents and mental health professionals about his legislation.?

Wise said the original school safety bill combined a “softening approach,” which strengthened support for mental health in schools, with a “hardening approach” that expanded resources to have School Resource Officers, or law enforcement officers, on school grounds. Wise, who was the chair of the Senate Education Committee at the time, called the school safety bill “very effective” since its passage.?

“What I’m hoping for this legislative session is funding,” Wise said. “We’ve got to make sure in the budget that we put money towards our mental health service providers, as well as our SROs, and I think this is the perfect time for us to be able to do it with a budget — hopefully the House presents to us — that has all of that in there.”?

In Kentucky, budget legislation originates from the House. Republican lawmakers have not filed their proposal so far.?

Additionally, KSVT praised the inclusion of trauma-informed language in 2019, calling it “a huge step in making schools safer and more supportive for students.” The team noted Meredith’s bill would eliminate wording that says “schools must provide a place for students to feel safe and supported to learn throughout the school day.”?

“If schools aren’t doing that, then how do we expect to raise test scores and achieve the academic and other educational goals we all want?” KSVT asked.?

Kentucky Youth Advocates Executive Director Terry Brooks said in a Friday statement that he is “optimistic that leadership in both chambers will, at the end of the day, actually reinforce and increase supports for building resiliency among young people.” As a former Kentucky educator, Brooks added that “addressing trauma is the first step in addressing reading and math proficiency.” When efforts that support resilience for Kentucky students are backed with budget funding and policy enhancements, “then this issue will become a core achievement of the 2024 session,” Brooks said.?

“Mental health challenges are at an unprecedented level for our kids,” he added. “Practices, policies and commitments which strengthen resilience and mitigate adversity are not icing on the cake — they are the cake. Along with the direct and positive impact that resilience supports yield, they are also indispensable as boosts for academic achievement.”

Bills aimed at DEI in General Assembly

Meredith’s bill is the second in the Kentucky Senate to be filed this session regarding DEI standards. Senate Majority Whip Mike Wilson filed Senate Bill 6, which would allow students and employees to sue public universities and colleges in Kentucky on grounds they were discriminated against for rejecting “divisive concepts.”?

Nationwide, DEI initiatives have become a target of conservative politicians who argue such frameworks favor some demographic groups, usually minority groups, over others. DEI concepts have been hotly debated in other states, such as Florida, where Republican presidential candidate and Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a law last year that prevents public universities and colleges from spending money on DEI programs.?

In addition to scrubbing trauma-informed language from state law, Meredith’s bill would also prevent school districts and charter schools from requiring “any statement, pledge, or oath, other than to uphold general and federal law, the United States Constitution, and the Constitution of Kentucky” as part of their employment, including any recruitment, hiring, promotion or disciplinary processes and divert education funding from DEI programs.?

Senate Democratic Floor Leader Gerald Neal, of Louisville, said Thursday afternoon that Senate Democrats were reviewing both anti-DEI bills. He said the ideas were part of a broad “national strategy” and Democrats are looking to have further discussions with Republicans about the intention behind the bills throughout the session.

Neal said Democrats had not sat down with Meredith to have an in-depth conversation about his bill. The minority floor leader also referred to comments both he and Republican Senate President Robert Stivers recently made on the Senate floor about working together on legislation that supports Kentuckians.?

“One of the things that we want to do is not get ahead of ourselves,” Neal said. “One of the things that we do is we talk to the sponsors of these things … because we want to really understand the intentionality of the sponsor of the legislation and give the opportunity to hear and respond.”

]]>Xian Brooks, left, their foster daughter, Brydie Harris, and son DJ on the day of DJ's adoption. (Photo by Once Upon a Flash, provided).

In Spring 2022, Brydie Harris and husband Xian Brooks got an email that would change their lives.?

A newborn Kentucky girl, flown to Tennessee for medical care, needed a foster family soon.?

“Xian started to read the email to me and was like, ‘would you want this newborn–’? and I was like ‘yes,’” Harris recalled. “He was like, ‘Do you want me to finish reading the email?’ and I was like, ‘No. Say yes.’”?

The rest of the email Brooks and Harris received would reveal that the baby had 15 centimeters of small intestine as part of a condition called short bowel syndrome. This is much shorter than the healthy length of 10-20 feet. That means the little girl, who shall remain anonymous since her adoption is pending, must use a central catheter line to get most of her nutrition.?

This line is both a “blessing and a curse” because it’s her main source of nutrition, Harris said. But it also means any sneeze, bacteria and the smallest of fevers can send the child, now 2, into the hospital for weeks.

While waiting to see if their family was a match for the little girl, the Louisville couple went to meet another child at St. Joseph Children’s Home.?

As they pulled into the parking lot to meet the boy, DJ, who would soon become their son, they got the call: their family was chosen to care for the baby girl, who they are now in the process of adopting.?

“Essentially, both of our kids came into our lives at the exact same moment, which is really wild,” Harris said.??

This holiday season, the Kentucky Lantern spoke to parents who have fostered, adopted and loved children with challenges, including age and medical complications, that often make finding a family for them difficult. Despite the challenges, they said, the relationships are worth it.?

Both of Harris’ and Brooks’ children were in a demographic that would be considered hard to place, they said. DJ, now 15, was 13 when he joined the family. Their foster daughter’s medical challenges made her potentially harder to place as well.?

This couldn’t stop Harris and Brooks from falling for their children. Both grew up with parents who opened their hearts and homes to children in need. Harris’ parents fostered youth, including teenagers who “kind of felt like nobody wanted them.”?

“We both kind of just grew up with that mentality that you help kids and teens in need and not because they’re in need but just because that’s what you should do is have an open family and an open heart to people who need that,” Harris said.?

There were more than 8,000 Kentucky children in Out Of Home Care (OOHC) with active placements in November, according to state data.?

The largest share of those children were placed in foster care homes. Half of children entering the public foster care system are between the ages of 6 and 18.?

More children were in Kentucky foster care from 2020-2022 than 2015-2017, the Lantern previously reported. And, fewer children left foster care and were reunited with biological families.?

‘We would do anything.’?

Harris and Brooks started fostering, first through the state and then privately, in 2019 and have fostered a total of five children. They “always knew we would do anything,” said Harris, including caring for babies who were exposed to substances in the womb.?

They know fostering or adopting teenagers or sick children frightens some people, they said. But, they want people to realize teenagers are children who need love, just like any other child.?

“For either of us, when you meet kids who are older or in sibling groups or are medically fragile, or all of these things that usually kind of scare people away, once you actually meet them, it’s just like, these are just children, you know?” Harris said.?

“Emotionally, I feel like my children are my biological children,” Harris said. “I feel like I give spiritual birth to them. I prayed for their existence for a long time. The way they came into our family was really kind of magical.”?

Harris added: “It’s very hard with (their toddler) being sick, but it’s not hard because she’s a foster child. It’s hard because she’s our daughter and we love her and it’s difficult to see her unhappy.”??

‘They gave us so much.’?

In Northern Kentucky, Christina and husband Justin Kleem stopped taking on new fosters this summer after fostering eight kids over the past six years, since 2017.

The two felt motivated to start fostering by their Christian faith, Christina said.?

“It wasn’t like, ‘oh, we think that we’re gonna save a kid’ type of thing,” she said. “We knew pretty early on that we wanted to work with children that didn’t have another party to stand for them and also to try to join with birth parents to kind of be their support.”?

Justin adopted her two children and they had three biological children together. Eventually, they would adopt two girls out of foster care.?

“Our family just grew” through the whole process, Christina said.?

“I can’t imagine our life without what our teens gave us,” she said. “It’s very easy to just live your life day to day and not realize what people around you are going through. I can see that every one of my other kids that are still living in our home – they live differently because of us fostering.”?

Originally, the couple worked with young children, then started taking teenagers in.?

Christina understands why some people shy away from fostering and adopting teenagers, she said. Many of them may have spent a significant amount of their formative years in the system, missing key development. Learning to adjust is a learning curve, she said, but worth it.?

“It’s kind of like the person that goes to prison and they don’t know what to do outside of it,” she explained.?

There are challenges — the older a child is, the more likely they are to bring with them trauma, baggage and, in some cases, behavioral issues, Christina admitted.?

But still: “I would do it 100 times again,” she said. And: “I would not do it differently.”?

Home for Christmas?

Christina and Justin’s family is much bigger than the seven children they have, she said. Even their fosters who moved on to other situations — back to their biological parents, residential care or aged out of the system — remain part of their family.?

She feels like all her kids – the ones she and Justin adopted and the ones they fostered — “gave us so much more” than they provided. In addition to getting their kids, they also gained branches of biological families as well. One child’s biological mother calls Christina a sister.?

Both Harris and Brooks and the Kleems said their families are now complete, though Harris said they’ll “never say never” to that changing.?

Their daughter is wrapping up her most recent hospital stay after getting a fever and needing to receive antibiotics via an IV. While there, the family kicked off Christmas celebrations, complete with a tree, lights and the toddler learning to say “Ho Ho Ho!”

The family will head home just in time for the holiday.?

And one of Kleem’s former foster daughters, Angie, is coming home for Christmas.?

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

A Ketron-Newell family portrait from 2019. Pictured, left to right, Elizabeth Newell, Gwenn Ketron, Natalie Newell, Raelinn Ketron, Rachelle Ketron, Marsha Newell, Patrick Newell, Meryl Ketron, Joseph Newell and Finley Ketron.

OWENTON — During a school-wide club fair in this northern Kentucky town, a school administrator stood watch as students signed up for a group for LGBTQ+ students and their allies.

After the club sign-up sheet had been posted, students wrote derogatory terms and mockingly signed up classmates, according to one of the club’s founders. The group eventually went to the administrator, who agreed to help.

Simply being able to post the sign-up sheet in school was a victory of sorts. For two years, the club, known as PRISM (People Respecting Individuality and Sexuality Meeting), gathered in the town’s public library, because its dozen members couldn’t find a faculty adviser to sponsor it. In fall 2022, after two teachers finally signed on, the group received permission to start the club on campus.

Much of that happened because of one parent, Rachelle Ketron. Ketron’s daughter Meryl Ketron, who was trans and an outspoken member of the LGBTQ+ community in her small town, had talked about wanting to start a Gay-Straight Alliance when she got to high school. But in April 2020, during her freshman year, Meryl died by suicide after facing years of harassment over her identity.??

Following Meryl’s death, Ketron decided to continue her daughter’s advocacy. She gathered Meryl’s friends and talked about what it might mean to start a Gay-Straight Alliance, a student-run group that could serve as a safe space for queer youth on campus. After trying, and failing, to get the school to sign off on the idea, the group decided to gather monthly at the public library, where its members discussed mental health, sex education and experiences of being queer in rural areas. Ketron, a coordinator of development at a community mental health center just across the border in Indiana, also founded doit4Meryl, a nonprofit that advocates for mental health education and suicide prevention, specifically for LGBTQ+ youth in rural communities like hers.

Around the country, LGBTQ+ students and the campus groups founded to support them have become a growing target in the culture wars. In 2023 alone, 542 anti-LGBTQ+ bills have been introduced by state legislatures or in Congress, according to an LGBTQ-legislation tracker, with many of them focused on young people. Supporters of the bills say schools inappropriately expose students to discussions about gender identity and sexuality, and parents deserve greater control over what their kids are taught. Critics say the laws are endangering already vulnerable students.?

Kentucky’s law, passed in March, is one of the nation’s most sweeping anti-LGBTQ+ laws, prohibiting school districts from compelling teachers to address trans students by their pronouns and banning transgender students from using school bathrooms or changing rooms that match their gender identity. The law also limits instruction on and discussion of human sexuality and gender identity in schools.?A separate section of the law bans gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth in the state.

“What started out as really a bill focused on pronouns and bathroom use morphed into this very broad anti-LGBTQIA+ piece of legislation that outlawed discussions of gender and sexuality, through all grades, and all subject matters,” said Jason Glass, the former Kentucky commissioner of education.

Glass left Kentucky in September to take a job in higher education in Michigan after his support for LGBTQ+ students drew fire from Republican politicians in Kentucky, including some who called for his ouster.

Because the law’s language is sometimes ambiguous, it’s up to individual districts to interpret it, Glass said. Some have adopted more restrictive policies that advocates say risk forcing GSAs, also known as Gender and Sexuality Alliances or Gay-Straight Alliances, to change their names or shut down, and led to book bans and the cancellation of lessons over concerns that they discuss gender or sexuality. Others have interpreted the law more liberally and continue to offer services and accommodations to transgender or nonbinary students, if parents approve.

Across the country, the number of GS

As is at a 20-year low, according to GLSEN, an LGBTQ+ education advocacy nonprofit. GLSEN researchers say there may be two somewhat contradictory forces at work. Fewer students may feel the need for such clubs, thanks to school curricula and textbooks that have become more inclusive of LGBTQ+ individuals and thanks to an increase in the number of school policies that explicitly prohibit anti-gay bullying. Conversely, the recent surge in anti-LGBTQ+ legislation, as well as the halt to extracurricular activities during the pandemic, may also be fueling the drop, the researchers said.?

Willie Carver, a former high school teacher and Kentucky’s Teacher of the Year in 2022, left teaching this year because of threats he faced as an openly gay man. Laws like the one in Kentucky legitimize and legalize harassment against LGBTQ+ kids, he said, and may even encourage it. “We’ve ripped all of the school support away from the students, so they’re consistently miserable and hopeless,” he said.

Coming out in fifth grade

Owenton is a picturesque farming community with rolling green hills and winding roads located halfway between Cincinnati and Louisville. Its population of about 1,682 is predominantly white and politically conservative: The surrounding county has voted overwhelmingly Republican in every presidential election since 2000.

Ketron moved here from Cincinnati in 2014 with her then-husband, seeking to live on a farm within driving distance of large cities. Shortly after the move, she recalled, a city official visited the property to give Ketron a rundown of expectations in the community — and a warning.?

“It was basically ‘You better watch what you do and don’t get on the bad side of people because one person might be the only person that does that job in this whole county.’ Do you understand what I mean?’ ‘Yup,’” Ketron recalled saying, “‘I understand what you mean.’”

A few years later, she met her now-wife, Marsha Newell, and the two began raising their blended family of eight children on the farm. They also started fostering LGBTQ+ kids. Ketron said her family is one the few in the county to accept queer kids. Their children were often met with hostility, Ketron said; other students made fun of them for having two moms and told them that Ketron and her wife were sinners who were “going to hell.”?

Ketron said the couple thought about moving, but beyond the financial and logistical obstacles, she worried about abandoning LGBTQ+ young people in the town. “Just because I’m uncomfortable or this is a foreign place for a queer kid to be doesn’t mean there aren’t queer kids born here every day,” she said.

After Meryl came out to family and friends in fifth grade, the bullying at school intensified, Ketron and Gwenn, Meryl’s younger sister, recalled. Few adults in Meryl’s schools took action to stop it, they said. When Meryl complained, school staff didn’t take her seriously and told her to “toughen up and move on,” Ketron said. (In an email, the high school’s new principal, Renee Boots, wrote that administrators did not receive reports of bullying from Meryl. Ketron said by the time Meryl reached high school, she’d given up on reporting such incidents.)?

That said, as she got older, Meryl became more outspoken. As a ninth grader, in 2019, she clashed with students who wanted to fly the Confederate flag at school; Meryl and her friends wanted to fly a rainbow flag. The school decided to ban both flags, Ketron said. After that, Meryl brought small rainbow flags and placed them around campus. (According to Boots, students were wearing various flags as “capes” and were advised not to do so as it was against school dress code.)??

Ketron said she generally supported her daughter’s advocacy, but sometimes wished she’d take a less combative approach. “You might need to dial it back a little bit,” Ketron recalled telling Meryl once, when her daughter was in eighth grade.?

Ketron recalled seeing Meryl’s disappointment; she said it was the only time she felt that she let her daughter down.

Clubs provide a sense of belonging

For years, the most effective wedge issue between conservatives and progressives was marriage equality. But when the Supreme Court in 2015 recognized the legal right of same-sex couples to marry, opponents of gay rights pivoted to focus on trans individuals, particularly trans youth. After early success with legislation banning trans kids from playing sports, conservative legislators began to expand their efforts to other school policies pertaining to LGBTQ+ youth.

The ripple effects of these laws on young people are becoming more apparent, said Michael Rady, senior education programs manager for GLSEN. Forty-one percent of LGBTQ youth have seriously considered suicide in the past year, according to a 2023 survey by The Trevor Project, an LGBTQ+ suicide prevention nonprofit. Nearly 2 in 3 LGBTQ+ youth said that learning about potential legislation banning discussions of LGBTQ+ people in schools negatively affected their mental health.

Konrad Bresin, an assistant professor in the department of psychology and brain sciences at the University of Louisville whose research focuses on LGBTQ+ mental health, said that for LGBTQ+ individuals just seeing advertising that promotes legislation against them has negative effects. “Even if something doesn’t pass, but there’s a big public debate about it, that is kind of increasing the day-to-day stress that people are experiencing,” he said.

Bresin said that student participation in GSAs can help blunt the effect of anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment, since the clubs provide students a sense of belonging.?

Supporters of Kentucky’s new law argue that the legislation creates necessary guardrails to protect students. Martin Cothran, spokesperson for The Family Foundation, the Kentucky-based conservative policy organization that advocated for the legislation, said the law is designed to keep students from being exposed to “gender ideology.”

Cothran said that nothing in the law impedes student speech, nor does it entirely prohibit traditional sex education. “It just says that you can’t indoctrinate,” he said. “Schools are for learning, not indoctrination.”

When the law, known as SB 150, went into effect last spring, Glass, the former education commissioner, said school districts were forced to scramble to update their curricula to comply with the bill’s restrictions. In some cases, that meant removing any information on sexuality or sexual maturation from elementary school health curricula, and also revising health, psychology and certain A.P. courses in middle school and high school, he said.?

Some families have sued. In September, four Lexington families with trans or nonbinary kids filed a lawsuit against the Fayette County Board of Education and the state’s Republican attorney general, Daniel Cameron, alleging that SB 150’s education provisions violate students’ educational, privacy and free speech rights under state and federal law. The families say that since the law passed, their kids have been intentionally misgendered or outed, barred access to bathrooms that match their gender identity and had their privacy disregarded when school staff accessed their birth certificates in order to enforce the law’s provisions.?

School districts that don’t comply fully with the law could face discipline from the state’s attorney general, said Chris Hartman, executive director of the Fairness Campaign, a Kentucky-based LGBTQ+ advocacy group.

Teachers from across the state have also shared stories about their schools removing pride flags and safe space stickers, banning educators from using trans students’ pronouns and names, and removing access to bathrooms for trans kids, according to Carver, the former Teacher of the Year, who is collecting that information as part of his work with the nonprofit Campaign for our Shared Future. Boyle County Schools Superintendent Mark Wade cited SB 150 as the reason for removing more than 100 books from the district’s school libraries.

Educators and school staff are fearful, said Carver. “It’s nearly impossible to know what’s happening because the law gets to be interpreted at the local level. So, the district itself gets to decide what the law’s interpretation will look like,” he said. “And teachers who before this were willing to speak out and advocate are, as a general rule, unwilling to speak publicly about what’s happening.”?

For supporters of the law, that may be the point. GLSEN’s Rady said the bills are often written in intentionally vague ways to intimidate educators and school district leaders into removing any content that might land them in trouble. This year, his group is focused on providing educators, students and families information about their rights to free speech and expression in schools, including their right to run GSAs, Rady said.?

‘Suicide is never one thing’

In March 2020, when the pandemic hit and schools went remote, Meryl, then a high school freshman, posted a video diary on social media. In it, she strums her ukulele, and shares a message to her friends. “Some of you guys don’t have social media, some of you guys don’t like being at home,” Meryl said in the video. “I won’t get to see you guys for a whole month which is awful because you guys make me have a 10 times better life, you guys make mountains feel like literally bumps and steep cliffs just feel like a little bit of walking down the stairs.”

The video ends with her saying she’ll see her peers in school on April 30, when schools were scheduled to reopen. On the morning of April 18, Meryl died.

Ketron, Meryl’s mother, had thought remote school would be a relief for her daughter after years of bullying in school buildings. But it was difficult to be separated from her friends, she said, and Meryl also knew some of them were struggling in homes where they did not feel accepted.

“Suicide is never one thing,” Ketron said. “A lot of times people talk about death by a thousand paper cuts. As sad as it sounds, for me to have that come out of my mouth, I feel like that really speaks to Meryl’s life. She had wonderful things, but it was just like thousands of paper cuts.”

For months after Meryl’s death, Ketron would read text messages on Meryl’s phone from her friends sharing stories about how she’d stood up for them in school and in the community. Ketron said she made a promise to herself — and to Meryl — that she was going to be loud like her daughter and “make it better.” In the spring of 2020, she started doit4Meryl.

“I don’t ever want this to happen again, ever, to anyone,” she said. “I never want someone to be in that place and pieces of it that got them there was hate and ignorance from another human being.”

In 2021, the anti-LGBTQ+ and anti-critical race theory book bans movement reached the Owenton community after a teacher in the district taught “The 57 Bus,” a nonfiction book that features a vocabulary guide explaining gender identities and characters who are LGBTQ+.

The book created an uproar in the town, with parents calling for its removal and for the educator to be disciplined. After that, Ketron said the few teachers who had seemed open to sponsoring the GSA no longer felt comfortable.

In mid-2021, Ketron decided to start the club herself, at the public library. Each month, a dozen or so kids gathered in one of the building’s study rooms, talking about what it means to be queer in rural Kentucky, and what they hoped to accomplish through their GSA. Some of them were Meryl’s friends, others were new to Ketron.?

In July 2022, the group held a Color Run, a 5K to bring together various advocacy groups from around the county and state to uplift people after the isolation of Covid. Later that year, they invited Carver to speak about his experiences as an openly gay man growing up in rural Kentucky. The students worked with Ketron and doit4Meryl to create a “Be Kind” campaign: They printed signs with phrases like “You’re never alone” and “Don’t give up,” along with information on mental health resources, and placed them in yards around town.?

In the fall of 2022, after a teacher agreed to serve as an advisor for the GSA, the school principal allowed the club on campus. While Ketron checks in with the students occasionally, the club is now student-led, she said. The past school year would have been Meryl’s senior year, and the club’s students were excited about finally being welcomed onto campus, Ketron said.?

Tragedy strikes again

Then Kentucky’s 2023 legislative session began with an onslaught of legislation targeting LGBTQ+ youth that eventually merged to become SB 150.?

Around the same time, tragedy entered Ketron’s life again: She lost one of her foster children, who was trans, to suicide. The loss of her daughters prompted her to spend countless hours in the state Capitol, attending committee meetings and hearings and signing up to testify against the anti-trans and anti-LGBTQ+ bills on the senate floor. She watched, devastated, as legislators quickly voted on and passed SB 150.?

“All I could think about was Meryl,” she said. “They’re just starting and this world is supposed to love them through this hard part. When you’re shaping yourself and instead we’re going to tell you that we don’t want you to exist.”

In Owenton, the district follows SB 150 as per law, said Reggie Taylor, superintendent of Owen County Schools. Little has changed as a result of the legislation, he said: “It’s been business as usual.” Trans and nonbinary students have long had a separate bathroom they could use and that hasn’t changed, he said, and the district offers a tip line for students to anonymously report bullying, as well as access to school counselors.?

Ketron, though, sees fallout. Fearful of bullying and other harms, she said that she and the other parents with trans kids in the school system are trying to get their children support by applying for help through Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. While 504 plans are typically for students with disabilities, they are sometimes used to help secure LGBTQ+ students services and accommodations, such as protection from bullying, mental health counseling and access to bathrooms that match their gender identity.?

SB 150 has also had a chilling effect on the work of the school’s GSA, according to Ketron. During the summer, after the law went into effect, PRISM members discussed changing the club’s name and direction to focus on mental health.?

Across the state, students and educators are grappling with what their schools will look like as the law takes hold. In March, Anna, a trans nonbinary student from Lexington, launched an Instagram account called TransKY Storytelling Project, anonymously documenting the impact of the new law on young people and teachers.

People shared examples of the ways the legislation affects them, such as making them afraid to go to school, erasing their identities and making the jobs of educators and librarians tougher. A middle school guidance counselor in rural Kentucky wrote that the new law makes it harder to connect with students and support them: “If we are the only ones students have, and we can’t provide them the care they desperately need and deserve, the future looks very bleak.”

Even in the state’s more progressive cities, the law has changed daily life in schools, Anna, the Instagram account’s curator said. The GSA at Anna’s Lexington high school used to announce club meetings and events on the loudspeakers and post flyers in school hallways, Anna said. But the group has since gone underground, to avoid bringing attention to its existence lest administrators force it to stop meeting.?

“The school felt so much safer knowing that [a GSA] existed because there were students like you elsewhere. You could go in and say, ‘Hey, I’m trying out this set of pronouns. I’m trying to learn more about myself. Can you all like call me this for a couple of weeks?’” Anna said. “It just allowed for a place where students like me could go.”

But while the absence of a GSA is concerning, Anna fears most the impact of SB 150 on students in rural parts of Kentucky. GSA members from rural communities have shared that they no longer have supportive school staff to advocate for their clubs because of the climate of fear created by the law, they said.?

That said, November’s election brought some hope for LGBTQ+ advocates: Cameron, the state attorney general who backed SB 150 and campaigned on anti-trans policies, lost his bid for the governorship to incumbent Andy Beshear, and several other candidates for office who advocated anti-trans policies were defeated too.

Back in Owenton, Ketron is working with Carver to plan a summit for Kentucky’s rural, queer youth. Ketron said she hopes the gathering will serve as a reminder for students that even though they may be isolated in their communities, there are people like them across the state.?

But as of this fall, participating in a GSA is no longer an option for students at the Owenton high school. Boots, the school principal, wrote in an email that the club had changed its focus, to one geared toward addressing “social needs across a variety of settings.”?

But according to Ketron, students said they were afraid to continue a club focused on LGBTQ+ issues in part because of SB 150. She offered to help students restart the club in the library, or at her house, she said, but members worried that would be too difficult because many of them have not come out to their families.?

Ketron said she’s not giving up. “At its core,” she said, a GSA is “a protective factor and so very needed, especially in a rural community.”

This story about?LGBTQ+ students in schools?was produced by?The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the?Hechinger newsletter.

Chronic absenteeism has risen among students in Kentucky's public schools. (Getty Images)

Kentucky’s new School Report Card shows the lingering effects of the coronavirus pandemic on student learning.

Interim Education Commissioner Robin Fields Kinney told reporters Tuesday that “a multi-year recovery period” will likely be needed “before school performance really gets back” to pre-pandemic levels.

Kinney and other state education officials briefed reporters on newly released assessment and education data from 2022-23. A wide range of metrics was reported for every public school — from math and reading performance to teacher demographics. The information is publicly available in a color-coded dashboard at Kentucky School Report Card.

Kinney said the data reveals a worrisome increase in student absenteeism.?

The rate of student absences is up by two-thirds from 2018-19, the last academic year before COVID-19 disrupted traditional attendance record keeping.

In the 2018-19 academic year, 119,581 students were considered chronically absent, or 17.8% of Kentucky students.

In the 2022-23 academic year, 198,524 students — or 29.8% — qualified as chronically absent.

Kinney attributed the increased absences not just to pandemic disruptions but also to challenges created when tornadoes hit Western Kentucky in 2021 and floods devastated Eastern Kentucky in 2022, as well as to “emotional trauma and stress” among young people.?

The Kentucky Department of Education defines chronic absenteeism as attending 90% or less of the time a student should spend in class.

“Every child deserves the opportunity for consistent attendance and a chance to thrive in the classroom. It is crucial that we work together and find solutions to combat chronic absenteeism,” Kinney said.

Kinney, who recently began serving as the interim education commissioner, said the state “must not underestimate” the coronavirus’s impact on student learning. When the pandemic reached Kentucky in March 2020, schools closed and switched to remote and virtual learning to prevent spread of the virus.?

“We know that changes in the way instruction was delivered from 2020 to 2022 had an impact on student learning, despite the tremendous efforts of Kentucky educators and parents to remediate those impacts,” Kinney said.?

Learning gaps

The federal Every Student Succeeds Act requires states to identify schools that need extra support and resources based on their significantly underperforming student subgroups. The lowest-performing schools are classified as needing Comprehensive Support and Improvement (CSI); the next lowest-performing are classified as needing Targeted Support and Improvement (TSI.)?

Kentucky has 1,484 schools. According to the data, 28 schools were classified as needing Comprehensive Support and Improvement? and 224 needed Targeted Support and Improvement. None were identified as needing Additional Targeted Support and Improvement (ATSI).?

In 2022, there were 401 TSI schools, but two closed, leaving 399 TSI schools.?. This year, 185 exited TSI status. Ten schools formerly CSI are now TSI schools.

The data show striking academic gaps for economically disadvantaged students, African American students and students who have disabilities and individual education plans.

Among high school students, the overall score for all students was 63.0. For African Americans it was 45.5 and for students with disabilities it was 40.4.

The percentage of students scoring proficient or distinguished in math and reading was double among those who come from homes that are more economically secure compared with their economically disadvantaged peers.

The numbers, which were released less than a week away from voters deciding Kentucky’s next governor and other statewide offices and ahead of the General Assembly’s 2024 legislative session, will be reviewed by lawmakers on the Interim Joint Committee on Education in Frankfort Wednesday morning. The data is typically released annually in the fall, months after students take assessments in the spring.?

Kinney said the Department of Education will continue to assist school districts and will continue work with the General Assembly to improve literacy attainment for the state’s youngest students and early learners.?

Assessment results

While student performance still has not rebounded to pre-pandemic levels, Kentucky elementary and middle schools did increase their reading and math performances in 2022-23.High schools maintained their performances. Elementary, middle and high schools increased their performances in science, social studies and combined writing areas. Students completed assessments in spring 2023.?

The state’s four-year graduation rate in 2022-23 was 91.4%. The five-year graduation rate was 92.5%.?

For Kentucky students who took the ACT during the 2022-23 school year, the average composite score was 18.5, up 0.2 from the previous year.?

Demographics in Kentucky schools

During the 2022-23 school year, a majority of Kentucky students were economically disadvantaged, 60.2%. Identifying such students depends on “being program or income eligible for free or reduced-priced meals.” In the same school year, 39.8% of students were non-economically disadvantaged.?

According to data from the previous school year, 2021-22, 59.9% of students were economically disadvantaged.?

Additionally, Kentucky schools are slightly more diverse when comparing current and last year’s data. During 2022-23, a majority of Kentucky students are white, 72.7%, down 0.8% from the previous year. Also in the same school year, 10.8% of Kentucky students are African American, 8.5% are Hispanic or Latino, and 7.2% identify as another demographic.?

A majority of faculty in Kentucky schools continue to be women, 77.2%, and white, 94.7%.?

Educational opportunities

Fewer students participated in Career and Technical Education programs in the 2022-23 school year than the previous school year. In 2022-23, the participation rate was 18%, down 6.4%.?

About 0.1% more students were identified as Gifted and Talented in the most recent school year for a total of 13.8%. Advanced coursework completion also slightly increased by 0.3%, for a total of 93.9%.?

For the 2022-23 school year, Kentucky’s attendance rate was 91.9%, but about 34% of all Kentucky students were identified as having chronic absenteeism, or being present 90% or less of full-time equivalency.?

School safety

The data released Tuesday showed that 13.5% of students have had behavior events reported to the state. Additionally, the percentage of students who received an out-of-school suspension last year was 5.9% and the percentage of students who had an in-school removal was 7.5%.?

Earlier this year, the Republican-led General Assembly approved legislation to expand student discipline methods in Kentucky classrooms before situations escalate into safety concerns. Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear, who is seeking reelection, signed the bill into law.?

Jamie Lucke contributed to this report.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Students gathered at the Capitol to protest SB 150, which removed access to gender-affirming medical care for trans minors. (Kentucky Lantern photo by McKenna Horsley)

Ysa Leon is questioning their future in the commonwealth. The outcome of Kentucky’s gubernatorial race this November will be a deciding factor.?

“I’ve told my family: Be prepared in November because that might change where I’m staying after I graduate in May,” said Leon, a 20-year-old nonbinary student at Transylvania University, where they are?president of the ?Student Government Association.

Leon and other transgender Kentuckians have been concerned for much of the year as Kentucky politics filled with heated discourse on the rights of trans people, specifically over what gender-affirming medical care for youth should be permitted in the state.?

After the Kentucky General Assembly passed one of the strongest anti-trans bills in the country, Senate Bill 150, Ray Loux, 17, decided to enroll in Fayette County Public Schools’ Middle College program for his senior year. He did not want to worry about which bathroom he should use, what pronouns his teachers will use and “not being able to talk about who I am with my friends in school.”

Ray is considering going to a college out of state.?

“I had a panic attack the other day because I wasn’t sure what my health care situation would look like going forward,” Ray said, as he must taper off his hormones while he is underage.?

Now, the issue of trans rights has reached the governor’s race.?

Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear, who is seeking a second term in office, has released a 15-second ad called ‘Parents.” It focuses on claims made by Republicans, including his opponent Republican Attorney General Daniel Cameron, that the governor supports “sex change surgery and drugs” for kids.

Wearing basic dad attire — a blue button down under a red quarter zip pullover — Beshear stares into the camera and says: “My faith guides me as a governor and as a dad.”?

He then repeats a familiar line — “all children are children of God” — before saying Cameron’s attacks are not true, adding: “I’ve never supported gender reassignment surgery for kids – and those procedures don’t happen here in Kentucky.”?

GOP backlash was swift, and rhetoric uplifting culture wars reached the annual Fancy Farm Picnic in West Kentucky earlier this month. Among his jokes for the day, Cameron riffed that come November Beshear’s pronouns will be “‘has’ and ‘been,’” and criticized the governor for protecting “transgender surgeries for kids.”

In a press conference last week, Cameron highlighted a letter from a University of Kentucky health clinic, stating it has performed “a small number of non-genital gender reassignment surgeries on minors who are almost adult,” but stopped after Kentucky’s ban on gender-affirming medical care for youth went into effect.?

Hours later, Beshear said in his press conference the letter was new to him, and added that had a bill that only banned gender reassignment surgeries for minors made its way to his desk, he would have signed it.?

“At the end of the day, how has this race gone here? Daniel Cameron’s taken this race to the gutter in a way that I’ve never seen,” Beshear said. “I mean, right now, I think if you ask him about climate change, he’ll say it’s caused by children and gender reassignment surgeries.”?

As politicians put a spotlight on gender-affirming medical care, advocates say the lives of trans Kentuckians — especially those of the commonwealth’s trans youth — are on the line.??

‘It’s hard to be a trans child anywhere’

Transgender youth are already vulnerable, and the way that politicians talk about trans people in general is “really dehumanizing,” said Oliver Hall, the director of Trans Health at Kentucky Health Justice Network. They work directly with transgender youth, a demographic that Hall said is being used as a “political football.”?

“It’s hard to be a kid. It’s hard to be a teenager in general,” Hall said. “And then it’s additionally hard to be a trans teenager. It’s hard to be a trans child anywhere.”

Leon, who came out as queer in 2020 and then as trans and nonbinary in 2021, said it took a lot of therapy to find themselves. At first, only their roommates and close friends referred to them with they/them pronouns in private.?

“When I heard it the first time, I felt like I took the biggest breath ever — this exhale that I’d been holding in for so long. All of this pent up anxiety was gone and I felt so good,” Leon said. “And it’s not that that fixed everything for me, but accepting yourself and having other people accept you changed my life. It changes everything for some people.”?

Kentucky’s trans youth no longer have access to gender-affirming medical care because of Senate Bill 150, which went into effect in July.?

The law, which Cameron’s office is defending against a legal challenge brought by the American Civil Liberties Union of Kentucky, bans gender-affirming medical care for anyone under 18, including forcing those already taking puberty blockers to stop. It also allows teachers to misgender trans kids, regulates which school bathrooms kids can use and limits the sex education students can receive.

Beshear vetoed the legislation, but the Republican supermajority in the General Assembly easily overrode it. In his rejection of the bill, Beshear wrote that he was doing so based on the rights of parents to make decisions about how their child is treated and that the law would allow government interference in medical care.?

“Improving access to gender-affirming care is an important means of improving health outcomes for the transgender population,” the governor wrote in his veto message.?

What someone’s gender-affirming care looks like is different for each transgender person, Leon said. They did not use puberty blockers because they came out as an adult, but socially transitioned with support from their friends and family. Gender-affirming medical care is also not always covered by health insurance companies.?

Having such laws on Kentucky’s books mixed with support from politicians running for the highest state office in the Commonwealth has “a detrimental effect on the physical and mental health of trans people,” Hall said.

(Photo provided)

Some in the trans community fear that, eventually, gender-affirming care for adults could be banned as well, said Ray’s mother, Shavahn Loux. While her son is in a “better situation than a lot of kids” because he will be an adult in a few months and could regain access to health care, she said “it’s scary” to think Ray’s access to hormone treatment in general could end completely.?

“I know a number of people who were thinking about coming here and are now no longer considering it because of this,” she said. “That’s true for trans individuals and non-trans individuals.”?