Ben Lovely, assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular genetics, looks through a zebrafish tank. Lovely is working with zebrafish to study fetal alcohol syndrome. (Photo provided)

LOUISVILLE — Over the next five years, University of Louisville researchers plan to expose about 1.5 million fish eggs to alcohol in hopes of better understanding fetal alcohol syndrome in humans.

Using a $2.3 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, researchers will specifically study zebrafish as a model for better understanding human facial defects associated with prenatal exposure to alcohol. They started their work in May and will finish in 2029.?

Ben Lovely, the study’s lead researcher and an assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular genetics at the university, said zebrafish are “a really strong model for humans” because they share more than 80% of the same genes.?

“If you have a gene that’s associated with cancer in humans, you’re probably going to find it in fish, and it can lead to cancer in a fish,” Lovely explained.?

Because of this, he told the Lantern, he can study the effects of alcohol on humans via the fish, learning more than he would be able to in a human study. Fish are well equipped for such a study, he said — he can study developing embryos outside the mother.?

“Part of the issue with looking at placental mammals like humans, like mice, is maternal effects and embryonic effects,” he said. “So you have two different things going on here.”?

With his zebrafish, which are raised in a facility on-site and “get fed and mate” for a living, he can take eggs that adult fish laid and? study them in petri dishes — about 100 at a time to ensure they don’t die from over-density. Zebrafish are a freshwater member of the minnow family.?

During their time in the dish, researchers control how much alcohol is added to the solution in each dish, which also has water and nutrients.?

“The alcohol goes right into the fish, gets right across the eggshell and into the fish itself,” he explained. The alcohol dose isn’t enough to kill the fish, he said.?

These fish are also perfect for monitoring early development.?

“They develop pigments once they reach adult stages, but as embryos, they’re transparent,” Lovely said. “You can see right through them. So we can actually watch the cells live in a developing fish over time. You can’t really do that in a placental mammal, because you’d have to remove the embryo to get that to happen.”?

Decreasing stigma?

Babies who were exposed to alcohol while in utero — especially in the early weeks when a person may not know they are pregnant — can be born with? fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs), which includes the incurable fetal alcohol syndrome.?

People born with this may have “abnormal facial features” like a smooth ridge between the nose and upper lip, a thin upper lip and small eyes, according to the Cleveland Clinic. Other symptoms can include learning problems, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression and more.?

Both the alcohol consumption and the facial features he is specifically studying can lead to stigma, Lovely said.?

“The first thing we see as humans is the face. So facial birth defects are hugely stigmatizing,” he said. “To understand their origins, their prognosis, everything about them is going to be key in really helping identify these issues early, if we can, especially prenatally, that would be more ideal.”?

Alcohol, too, “has its own stigma,” he said.?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in 2019 that about 42% of pregnancies in the United States are unintended. The early weeks and months of pregnancy are a key time for the developments of FASD, according to the Mayo Clinic.

“So you combine those two: there are a lot of individuals who are drinking and do not know they’re pregnant,” Lovely said. “They don’t want to be accused of harming their child because they didn’t know, right? That’s the stigma. So it’s very difficult for him to do human studies. It’s very difficult to find patients — very few mothers want to admit to this.”?

But through his zebrafish study, he said, he hopes to move in the direction of genotyping a person to see their sensitivity to alcohol and look at the issue more from a gene perspective and less from a social perspective.?

“A lot of researchers now … say ‘prenatal exposure,’ we don’t say ‘the mother drank,’” he said. “We don’t say anything about the mother, to avoid stigmatizing the mother. So we try to couch it from ‘this has happened to the developing embryo,’ not ‘this was done to the developing embryo.’”?

The CDC said this year that about 1 in 20 school-aged children in the country could have FASDs.? Not every fetus that’s exposed to alcohol will develop FASD issues.?

Because of this, the University of Louisville says that “understanding what genes might increase that risk could lead to better therapeutics and help mothers make safer, more informed choices.”?

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Cecily Cornett grabs bags of blood to include in a shipment from the Kentucky Blood Center to a Lexington-area hospital on May 22, 2024, in Lexington. (Kentucky Lantern photo by Arden Barnes)?

Quintissa Peake, like many people, doesn’t like needles. But the Letcher County woman can’t choose to avoid them.

She lives with sickle cell anemia, a genetic blood disorder that is painful and primarily affects people of African descent.

People with sickle cell often need blood transfusions to replace their damaged hemoglobin cells? – which are in the shape of a C — with normal hemoglobin — in the shape of a disk. (Hemoglobin is the protein that carries oxygen to tissue).?

In her 43 years of life, Peake has had more than 500 units of blood transfused into her body.

As it goes into her veins, she feels the cold.?

The blood she receives, which comes from and entirely depends on donors, helps her manage what can be excruciating pain throughout her entire body.?

Many people need blood for various treatments and operations. Those include people like Peake who have sickle cell disease, cancer patients, gunshot victims. It’s also needed for surgeries, organ transplants, childbirth and more. A quarter of the blood supply goes to cancer patients.?

Traumas like mass shootings deplete supply quickly. The Old National Bank shooting in Louisville in 2023, for example, required 80 donations.?

One in four people will need blood at some point in their lives, according to the Kentucky Blood Center (KBC).

And while the need is ongoing, Kentucky has a shortage of blood. Nationally, not nearly enough people donate — only 3% of people who are eligible.?

“The need for blood is always there,” Peake said. “I would just like to encourage people to donate … especially when (there’s) a shortage.”???

Quintissa’s story

Peake, who is from and lives in Neon, was diagnosed with sickle cell anemia at 11 months old. Her mother tells her that, as a baby, she cried a lot and wouldn’t move her arms and legs.?

Both her parents were sickle cell carriers, though they didn’t live with the disease.?

As a child, Peake bounced back from transfusions and hospital stays quickly. But, as more time passes, she deals with more nagging chronic pain.?

Peake’s pain ranges from mild and unrelenting to sharp and throbbing. Both are unpredictable. They interrupt her ability to hold a job and to enjoy carefree travel.??

She has a daily prescription for morphine but still feels pain. Sometimes, she has to go to the emergency room for hydration treatments and pain management by IV. She never knows when doctors are going to tell her it’s time for another blood transfusion.?

When that happens, she needs blood already on the shelf. She is A positive, but can receive blood from A positive, A negative, O positive, and O negative donors. Because she has received so much donor blood in her life, she also needs blood with specific antigens, which KBC tests for in its Reference Laboratory.?

An antigen is a “substance that causes the body to make an immune response against that substance,” according to the National Cancer Institute. If a person who needs specific ones gets a transfusion with the wrong ones, their immune system will attack the donor cells. This can lead to serious negative reactions and even death, according to Eric Lindsey, the KBC spokesman.?

Amanda Clark, the tech-in-charge at the KBC reference lab, said every month her team sends out about 40 units of special blood for sickle cell patients who need to exchange their whole body’s supply. (An adult who weighs 150 to 180 pounds has about 10 units of blood in their body, according to the American Red Cross).??

Once KBC comes across donors who have antigens that match specific patient needs, the reference lab holds onto those products.?

“These units are held back for … most of the time, cancer patients or sickle cell patients,” Clark said. “Patients that are transfused very often … make antibodies, and they require special blood.”??

Such is Peake’s situation. If she has to wait a few days for the blood, she’s forced to linger in pain. She usually gets her transfusions in Lexington at UK Healthcare, which is a three-hour drive each way, adding yet another complication to her care.?

For the last 16 years, she’s lived with a port that’s implanted under her collar bone on the right side. This ensures she gets stuck only once every time she needs a transfusion or other IV treatment. Before that, her small veins meant she suffered through multiple sticks before getting relief. One time, she stopped counting at 25 needle pricks.?

Her chronic pain — and the extraordinary financial weight of her necessary care — takes a toll on her mental health. She has Medicare, which covers 80% of her medical bills. While that is helpful, she said, her 20% out-of-pocket portion can still reach $60,000, which she tackles through payment plans.?

This “astronomical” burden is a close second stresser to her physical health.?

She tries to focus on the positive and “practice gratitude,” she said.?

“In an ideal world, I would love to not have chronic pain or not deal with it daily,” she said. “However, it’s … something that I’ve just had to come to the realization that: I may not have another 100% pain-free day.”?

Kentucky’s blood shortage?

The COVID-19 pandemic sent blood donations plummeting, which caused a shortage. During a time when highly infectious variants spread quickly — and before vaccines hit the market — many were reluctant to donate.?

Mobile drives, too, could no longer go into schools and collect from much-needed young donors.?

As a result, the blood supply dwindled. Hospitals dipped into the reserve supplies, leaving shelves sparse.?

Kentucky still hasn’t fully recovered.?

For KBC, every day is a juggling act to balance public appeal for donations with hospital demand for products and rotating expiration dates.??

Often right after an emergency — like the 2023 mass shooting in Louisville — donations pour in. While this is always welcome, it’s the supply already processed and on the shelves that is most useful.?

That’s why regular donation is so important, according to Liz Becker, the vice president of donor services at KBC.?

“You never know when it’s going to be you or a family member or a loved one that’s going to need it,” she said. “It’s the blood that’s already on the shelf that’s going to? make the difference.”?

KBC is primarily focused on keeping blood in Kentucky, though it has helped other states in cases of severe emergencies, like a recent school shooting in Iowa that depleted the Hawkeye State’s local supply.?

KBC uses giveaways to incentivise people to donate, including an ongoing lottery for Taylor Swift Eras Tour tickets in Indianapolis this fall worth thousands of dollars. The giveaways are funded with the money hospitals pay for the blood products on their shelves.?

From May 28 through June 29, anyone who donates at any KBC location will be entered to win two Eras Tour tickets for Nov. 3 in Indianapolis. The winner will also get a $500 gift card to help with travel.

From May 28 through June 29, anyone who donates at any KBC location will be entered to win two Eras Tour tickets for Nov. 3 in Indianapolis. The winner will also get a $500 gift card to help with travel.

Donors also get a t-shirt that says “It’s me, hi, I’m the hero, it’s me,” which is inspired by Swift’s lyrics. People who donate on Mondays and Tuesdays will also receive friendship bracelets, which are often exchanged by people in the Swift fandom at concerts.

This giveaway has already increased donations, especially among young and first time donors, and staff hope that continues.

The number of young donors dipped dramatically during the pandemic, in part because mobile drives couldn’t go into schools. In recent years, schools have allowed mobile blood drives to resume.

Still, donations haven’t reached pre-pandemic levels yet, which staff say is possibly because of lingering discomfort due to COVID-19.

Giveaways like this work for the Kenner family, who recently donated blood in Lexington in exchange for Kings Island tickets. They’ve donated for nothing before, but said they’ll schedule their donations around a good giveaway.?

Adam Kenner, 19, started donating at 16 and tries to donate a couple of times a year. His parents, he said, instilled in him a desire to help others.?

“I just want to help,” said Kenner, who has the type of blood Peake often gets transfused — O-positive. “I can be the person who helped someone.”?

His father, Andrew, is a Lexington firefighter and paramedic. He sees up close when people need blood.?

He’s also donated blood since he was 16, as often as he can. He learned about the need for regular blood donations years ago in a class, and has seen loved ones need blood for cancer treatments and other illnesses.?

“I kind of got to practice what I preach, you know?”?

The anatomy of the blood supply?

The blood supply is, itself, like a human body. At the KBC headquarters in Lexington, dozens of moving parts pump the supply out to hospitals and other facilities. The moments a donor spends on the table are just the beginning of an intricate process of testing, separating, creating products and infusing.?

Depending on the donor’s demographics, lab technicians will decide what products they can make out of a blood donation, according Liz Counts, KBC’s vice president of technical services.?

“Generally, there’s going to be a red cell product, and then there’s going to be a plasma or platelet product,” she explained.?

Kentucky scientists place whole blood units in centrifuges to separate red cells from plasma. Test tubes are driven to Cincinnati every day and put on a commercial flight to Atlanta, where a different lab tests for West Nile virus, syphilis and other infectious diseases.?

If donated blood tests positive for any virus or disease that makes it unusable, it’s incinerated.?

Pre-donation screening questions catch a lot of potential issues, Counts said, though staff do get positive results, especially for syphilis and hepatitis C. Some test results go “hand in hand” with Kentucky’s high rate of substance use, she said, which is the reason phlebotomists do a track mark inspection of donors’ arms.??

Within 24 hours — unless there are unforeseen delays with the testing process — donor blood is ready for distribution.?

“Every day we have to make sure that we’ve collected … 250, if not more, blood products,” Counts said. “We rotate the blood through the hospitals — they’re constantly transfusing. So there’s always a constant need for fresh blood and to keep the inventory robust.”?

In order to make up for the shortage COVID-19 caused — and to account for donors who come in but aren’t able to give blood that day — KBC needs 400 donors a day, said Lindsey, the center spokesman.?

KBC is currently not bringing in those 400 donations a day. This means the supply on the shelves is easily depleted from day to day. This is especially true for the O-negative supply, which is the universal type and can go to anyone. This blood type is often used in emergencies when a patient’s blood type isn’t known. According to the American Red Cross, just 7% of Americans have an O-negative blood type.?

Sometimes people don’t donate because they are scared of needles, Counts said.?

But: “That is such a small part of blood donation,” she said. “And the number of people that you’re helping — it just doesn’t even match up to the little bit of pain you could possibly feel.”??

Moving parts?

Among the blood supply’s moving parts are blood couriers like Scott Arnold, who is in his seventh year driving for the Kentucky Blood Center. He’s worked at KBC in other roles for 16 years. Each day he drives to six local hospitals and drops off coolers full of human blood. KBC supplies more than 70 facilities around the state in 90 counties, and couriers drive as far as Pikeville every day.?

Around 9 a.m. on a recent Tuesday, Arnold packed the back of his van full of human blood, packaged in coolers with ice.?

Once he arrives at the hospitals on his route, Arnold walks to lab after lab to hand-deliver coolers. If facilities have blood on their shelves that’s about to expire, they send it with him to whichever facility in his route that can use it.?

Usually it goes to UK Healthcare, which receives 40% of KBC’s blood supply.?

The job gives him “inner peace,” he told the Lantern as he drove down Harrodsburg Road. “Not a lot of people have a job where you can actually serve others.”??

Arnold said he feels “a sense of pride for helping somebody survive.”

In addition to her gratitude practice, Eastern Kentucky’s Peake finds comfort in her online sickle cell support groups and her faith. She also speaks to medical school students about her disease and promotes blood donation. She encourages others to face their fears of needles that may keep them from donating.?

“It’s something that helps me and it has helped my life. … I know it’s something that can help others,” she said. “Your fears are valid, and it’s hard to get over some things. But if you can get over your fears, just think of how much life you can be adding to someone that you don’t even know. And the person who’s on the receiving end, I can guarantee, is very thankful and grateful for your time and your effort.”?

Donors can give whole blood, double red cells and platelets. Whole blood donations take 45 minutes and donors can give every 56 days. Double red donors can give every 112 days, and each donation takes about 30-40 minutes. Platelet donors can give every 14 days, and each donation takes between 45 minutes and an hour and a half.?

Donate blood in Kentucky?

To donate blood in Kentucky you must:?

- Be 17 years old or 16 with parental consent

- Be in good health

- Weigh at least 110 pounds?

- Have a photo identification

Donate at:?

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

A line of waiting vehicles is seen while a Bluewater Diagnostic Laboratories technician administers a COVID-19 test at Churchill Downs on January 10, 2022 in Louisville. (Photo by Jon Cherry/Getty Images)

From spring break parties to Mardi Gras, many people remember the last major “normal” thing they did before the novel coronavirus pandemic dawned, forcing governments worldwide to issue stay-at-home advisories and shutdowns.

Kentucky Senate votes to bar employers, schools from requiring COVID-19 vaccine

Even before the first case of COVID-19 was detected in the U.S., fears and uncertainties helped spur misinformation’s rapid spread. In March 2020, schools closed, employers sent staff to work from home, and grocery stores called for physical distancing to keep people safe. But little halted the flow of misleading claims that sent fact-checkers and public health officials into overdrive.

Some people falsely?asserted covid’s symptoms were associated with 5G wireless technology. Faux cures and?untested treatments?populated social media and political discourse. Amid uncertainty about the virus’s origins, some people proclaimed?covid didn’t exist at all. PolitiFact named “downplay and denial” about the virus its?2020 “Lie of the Year.”

Four years later, people’s lives are largely free of the extreme public health measures that restricted them early in the pandemic. But covid misinformation persists, although it’s now centered mostly on vaccines and vaccine-related conspiracy theories.

PolitiFact has published?more than 2,000 fact checks?related to covid vaccines alone.

“From a misinformation researcher perspective, [there has been] shifting levels of trust,” said Tara Kirk Sell, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “Early on in the pandemic, there was a lot of: ‘This isn’t real,’ fake cures, and then later on, we see more vaccine-focused mis- and disinformation and a more partisan type of disinformation and misinformation.”

Here are some of the most persistent covid misinformation narratives we see today:

A loss of trust in the vaccines

Covid vaccines were quickly developed, with U.S. patients receiving the first shots in December 2020, 11 months after the first domestic case was detected.

Experts credit the speedy development with helping to?save millions of lives?and preventing hospitalizations. Researchers at the University of Southern California and Brown University calculated that?vaccines saved 2.4 million lives?in 141 countries starting from the vaccines’ rollout through August 2021 alone. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data shows there were 1,164 U.S. deaths provisionally?attributed to covid?the week of March 2, down from nearly 26,000 at the pandemic’s height in January 2021, as vaccines were just rolling out.

But on social media and in some public officials’ remarks, misinformation about covid vaccine efficacy and safety is common.?U.S. presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has built his 2024 campaign on a movement that seeks to legitimize conspiracy theories about the vaccines. PolitiFact made that its 2023 “Lie of the Year.”

PolitiFact has seen claims that spike proteins from vaccines are?replacing sperm?in vaccinated males. (That’s?false.) We’ve researched the assertion that vaccines can change your DNA. (That’s?misleading and ignores evidence). Social media posts poked fun at Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce for encouraging people to get vaccinated, asserting that the vaccine actually shuts off recipients’ hearts. (No, it doesn’t.)?And some people pointed to an American Red Cross blood donation questionnaire as evidence that shots are unsafe.?(PolitiFact rated that False.)

Experts say this misinformation has real-world effects.

A September 2023 survey by?KFF found that 57% of Americans?“say they are very or somewhat confident” in covid vaccines. And those who distrust them are more likely to identify as politically conservative: Thirty-six percent of Republicans compared with 84% of Democrats say they are very or somewhat confident in the vaccine.

Immunization rates for routine vaccines for other conditions have also taken a hit. Measles had been eradicated for more than 20 years in the U.S. but there have been recent outbreaks in?states including Florida,?Maryland, and Ohio. Florida’s surgeon general has expressed?skepticism?about vaccines and?rejected?guidance?from the CDC about how to contain potentially deadly disease spread.

The vaccination rate among kindergartners has declined from 95% in the 2019-20 school year to 93% in 2022-23, according to the?CDC. Public health officials have set a 95% vaccination rate target to prevent and reduce the risk of disease outbreaks. The CDC also found?exemptions had risen to 3%, the highest rate ever recorded?in the U.S.

Unsubstantiated claims that vaccines cause deaths or other illness

PolitiFact has seen repeated and unsubstantiated?claims that covid vaccines have caused mass numbers of deaths.

A recent widely shared post claimed?17 million people had died?because of the vaccine, despite contrary evidence from multiple studies and institutions such as the World Health Organization and CDC that the vaccines are safe and help to prevent severe illness and death.

Another online post claimed the booster vaccine had?eight strains of HIV?and would kill 23% of the population. Vaccine manufacturers publish the?ingredient lists; they do not include HIV. People living with HIV were among the people?given priority access?during early vaccine rollout to protect them from severe illness.

Covid vaccines also have been blamed for?causing Alzheimer’s?and?cancer. Experts have found no evidence the vaccines cause either conditions.

“??You had this remarkable scientific or medical accomplishment contrasted with this remarkable rejection of that technology by a significant portion of the American public,” said Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

More than three years after vaccines became available, about 70% of Americans have completed a primary series of covid vaccination,?according to CDC figures. About 17% have gotten the most recent?bivalent booster.

False claims?often pull?from and misuse data?from the?Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. The database, run by the CDC and the FDA, allows anybody to report reactions after any vaccine. The reports themselves are unverified, but the database is designed to help researchers find patterns for further investigation.

An?October 2023 survey published in November by the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania found 63% of Americans think “it is safer to get the COVID-19 vaccine than the COVID-19 disease” — that was down from 75% in April 2021.

Celebrity deaths falsely attributed to vaccines

Betty White, Bob Saget,?Matthew Perry, and?DMX?are just a few of the many celebrities whose deaths were falsely linked to the vaccine. The anti-vaccine film?“Died Suddenly” tried to give credence to false claims that the vaccine causes people to die shortly after receiving it.

Céline Gounder, editor-at-large for public health at KFF Health News and an infectious disease specialist, said these claims proliferate because of two things:?cognitive bias and more insidious motivated reasoning.

“It’s like saying ‘I had an ice cream cone and then I died the next day; the ice cream must have killed me,” she said. And those with preexisting beliefs about the vaccine seek to attach sudden deaths to the vaccine.

Gounder experienced this?personally when her husband, the celebrated sports journalist Grant Wahl, died while covering the 2022 World Cup in Qatar. Wahl died of a ruptured aortic aneurysm but anti-vaccine accounts falsely linked his death to a covid vaccine, forcing Gounder to?publicly?set the record straight.

“It is very clear that this is about harming other people,” said Gounder, who was a?guest?at United Facts of America in 2023. “And in this case, trying to harm me and my family at a point where we were grieving my husband’s loss. What was important in that moment was to really stand up for my husband, his legacy, and to do what I know he would have wanted me to do, which is to speak the truth and to do so very publicly.”

Out-of-control claims about government control

False claims that the?pandemic was planned?by government leaders and those in power abound.

At any given moment, Microsoft Corp. co-founder and philanthropist Bill Gates, World Economic Forum head Klaus Schwab, or Anthony Fauci, former director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, are blamed for orchestrating pandemic-related threats.In November, Rep. Matt Rosendale, R-Mont., falsely claimed Fauci “brought” the virus to his state a?year before the pandemic.?There is?no evidence?of that. Gates, according to the narratives, is using dangerous vaccines to push a depopulation agenda. That’s?false. And Schwab has not said he has an “agenda” to establish a totalitarian global regime using the coronavirus to depopulate the Earth and reorganize society. That’s part of a?conspiracy theory?that’s come to be called?“The Great Reset”?that has been?debunked?many?times.

The United Nations’ World Health Organization is frequently painted as a global force for evil, too, with detractors saying it is using vaccination to control or harm people. But the WHO has not declared that?a new pandemic?is happening, as some have claimed. Its current pandemic preparedness treaty is in no way positioned to remove human rights protections or restrict freedoms, as?one post said. And the organization has not announced plans to deploy troops to corral people and?forcibly vaccinate them. The WHO is, however, working on a new treaty to help countries improve coordination in response to future pandemics.

This story is republished from KFF Health News, a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.

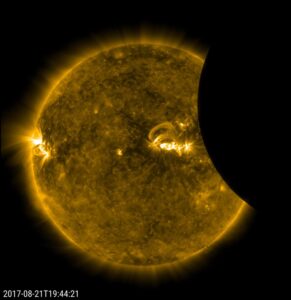

]]>The path of totality and partial contours crossing the U.S. for the 2024 total solar eclipse occurring on April 8, 2024. (NASA photo)

LOUISVILLE — As millions gear up for the total solar eclipse on Monday, Kentuckians are being cautioned to protect their eyes from sun damage and prepare for traffic delays.?

The 2024 total solar eclipse — the last one for at least two decades — will happen Monday, April 8.?

The time of the eclipse varies by location. The totality phase will enter Kentucky around 2 p.m., CDT, in parts of Fulton and Hickman counties before reaching Ballard, McCracken, Livingston, Crittenden, Union and Henderson counties along the Ohio River. It will also clip Carlisle, Graves, Webster and Daviess counties.

?The full darkening will be visible in Louisville at 3:07 p.m., EST.

To search for eclipse times by ZIP code and find other information, visit https://science.nasa.gov/eclipses/future-eclipses/eclipse-2024/where-when.?

A solar eclipse is when the moon passes between the sun and the Earth, blocking the sun and causing momentary darkness, according to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). There was a total solar eclipse in 2017, as well, but NASA says the Monday eclipse is “even more exciting” because it has a wider path.?

The Kentucky Transportation Cabinet estimates the eclipse will attract 150,000 visitors to Western Kentucky, where a dozen counties are in or near the path of totality.? This will lead to “major” traffic delays. For more information on traffic delays, visit https://2024-solar-eclipse-kytc.hub.arcgis.com/.?

“You want to make sure that you see this once in a lifetime event — for some, twice in a lifetime event — but that you do it safely,” Gov. Andy Beshear said Thursday.?

“We want people to take in this incredible event, but we also want them to be prepared for potential heavy traffic as everyone heads to and from the main eclipse corridor,” Transportation Secretary Jim Gray said. “We have some simple suggestions for visitors: Arrive early and pack the essentials such as water, eclipse glasses and plenty of patience for navigating crowded highways.”

Protect your eyes?

Dr. Patrick Scott, an optometrist with UofL Health, said looking at the eclipse — even for a few seconds — can cause damage to the eyes.?

“We don’t typically look at the sun on a day to day basis because … it can be damaging, it’s too much light,” he said.?

During an eclipse, people are “tempted to look up,” he said, but should resist the urge because it can “cause permanent damage to the receptive cells of the retina.”?

Children are most at risk of damage, he said, as well as people who take medication like tetracycline or amiodarone, which can make them more vulnerable to sun damage.?

Sunglasses are a definite no-go for eclipse viewing, Scott said. They do not filter out the sun’s rays enough to avoid damage.?

“Eclipse glasses should be the only type of viewing glasses that you would use to look at the eclipse,” he said. When buying eclipse glasses, he added, be sure to check for the label that says “ISO 12312-2.”?

People who are looking to reuse eclipse glasses from the 2017 eclipse should make sure the lenses are scratch-free, said Scott.?

“If there are scratches or any type of blemish that can allow the sun’s rays to get through,” he said, “I would not use them.”??

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Research by Kevin Sokoloski, left, was funded through the UofL Center of Biomedical Research Excellence in Functional Microbiomics, Inflammation and Pathogenicity. Richard Lamont, center, co-leads the project, which has received an additional grant of nearly $12 million. (Photo provided).

University of Louisville researchers hope to better understand conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, heart disease and diabetes and how to best treat them through a nearly $12 million, five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health.

Over the next half-decade, the researchers will study connections between microorganisms like bacteria, yeasts, fungi, viruses and protozoans and diseases, UofL said Thursday.?

The researchers were originally awarded a grant in 2018 from the Center of Biomedical Research Excellence. This $11.7 million extends that research, which includes studying microorganisms in the mouth, GI tract and the blood-brain barrier.??

The research “could lead to life-changing therapies, treatments and more that could dramatically improve the lives of people living with numerous conditions,” Kevin Gardner, executive vice president for research and innovation, said in a statement.?

Multiple researchers will investigate:?

- Periodontitis, a common condition which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says can include the gums pulling away from teeth. People with the condition may lose teeth or have tooths loosen. Smoking and diabetes are risk factors for periodontitis.?

- The GI tract pathogen C. difficile, which the Mayo Clinic says can cause “life threatening damage” to the colon.?

- The blood-brain barrier (BBB), which the Cleveland Clinic says is “a tightly locked layer of cells that defend your brain from harmful substances, germs and other things that could cause damage.”?

In 2021, 1,632 Kentuckians died from Alzheimer’s Disease, according to the CDC. Kentucky also has high rates of cancer mortality, heart disease and diabetes.? ?

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

A rock climber gets an intimate view of Kentucky geology. (Photo courtesy of Beattyville/Lee County Tourism)

The powerful role of geologic forces in shaping our environment, natural resources and daily lives will be the focus of an Aug. 9 talk in Lexington.

State geologist Drew Andrews, acting director of the Kentucky Geological Survey, will discuss the ways geology affects lives more than most people realize. He will also give an overview of services offered by the Kentucky Geological Survey, according to a news release from the Kentucky Academy of Science.

The event starts at 7 p.m. on Wednesday at Pivot Brewing, 1400 Delaware Ave.

The event is open to the public. There is no admission charge. Attendees will have opportunities to purchase food and drink and are welcome to stay after the talk to enjoy the gathering of science enthusiasts. One guest will receive a door prize, a geology-themed coffee mug.

The event is sponsored by the Kentucky Academy of Science, the state’s largest science organization with more than 4,000 scientists, students, educators, and advocates working together to promote science in Kentucky.

]]>