A young boy places a stone on the grave of his father as friends and family gather to commemorate the first anniversary of his death from heroin overdose. Between 2011 and 2021, more than 321,000 children across the U.S. lost a parent to a drug overdose, according to a recent federal study. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)

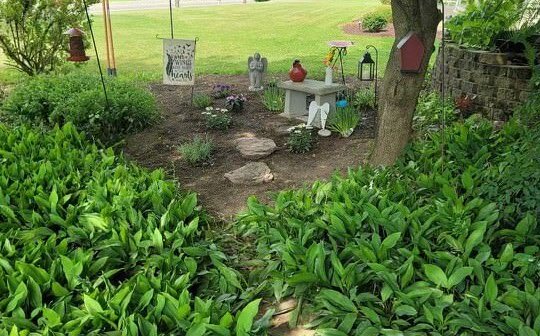

Every day, 8-year-old Emma sits in a small garden outside her grandmother’s home in Salem, Ohio, writing letters to her mom and sometimes singing songs her mother used to sing to her.

Emma’s mom, Danielle Stanley, died of an overdose last year. She was 34, and had struggled with addiction since she was a teenager, said Brenda “Nina” Hamilton, Danielle’s mother and Emma’s grandmother.

“We built a memorial for Emma so that she could visit her mom, and she’ll go out and talk to her, tell her about her day,” Hamilton said.

Lush with hibiscus and sunflowers, lavender and a plum tree, the space is a small oasis where she also can “cry and be angry,” Emma told Stateline.

Hundreds of thousands of other kids are in a similar situation: More than 321,000 children in the U.S. lost a parent to a drug overdose in the decade between 2011 and 2021, according to a study by federal health researchers that was published in JAMA Psychiatry in May.

In recent years, opioid manufacturers, distributors and retailers have paid states billions of dollars to settle lawsuits accusing them of contributing to the overdose epidemic. Some experts and advocates want states to use some of that money to help these children cope with the loss of their parents. Others want more support for caregivers, and special mental health programs to help the kids work through their long-term trauma — and to break a pattern of addiction that often cycles through generations.

The rate of children who lost parents to drug overdoses more than doubled during the decade included in the study, surging from 27 kids per 100,000 in 2011 to 63 per 100,000 in 2021.

Nearly three-quarters of the 649,599 adults between ages 18 and 64 who died during that period were white.

The children of American Indians and Alaska Natives lost a parent at a rate of 187 per 100,000, more than double the rate among the children of non-Hispanic white parents and Black parents (76.5 and 73.2 per 100,000, respectively). Children of young Black parents between ages 18 and 25 saw the greatest loss increase per year, according to the researchers, at a rate of almost 24%. The study did not include overdose victims who were homeless, incarcerated or living in institutions.

The data included deaths from illicit drugs, such as cocaine, heroin or hallucinogens; prescription opioids, including pain relievers; and stimulants, sedatives and tranquilizers. Danielle Stanley, Emma’s mother, had a combination of drugs in her system when she died.

At-risk children

Children need help to get through their immediate grief, but they also need longer-term support, said Chad Shearer, senior vice president for policy at the United Hospital Fund of New York and former deputy director at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s State Health Reform Assistance Network.

An estimated 2.2 million U.S. children were affected by the opioid epidemic in 2017, according to the hospital fund, meaning they were living with a parent with opioid use disorder, were in foster care because of a parent’s opioid use, or had a parent incarcerated due to opioids.

“This is a uniquely at-risk subpopulation of children, and they need kind of coordinated and ongoing services and support that takes into account: What does the remaining family actually look like, and what are the supports that those kids do or don’t have access to?” Shearer said.

Ron Browder, president of the Ohio Federation for Health Equity and Social Justice, an advocacy group, said “respecting the cultural traditions of families” is essential to supporting them effectively. The state has one of the 10 highest overdose death rates in the nation and the fifth-highest number of deaths, according to 2022 data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For second year in a row, Kentucky overdose deaths decrease?

The goal, Browder said, should be to keep kids in the care of a family member whenever possible.

“We just want to make sure children are not sitting somewhere in a strange room,” said Browder, the former chief for child and adult protection, adoption and kinship at the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services and executive director of the Children’s Defense Fund of Ohio.

“The child has gone through trauma from losing their parent to the overdose, and now you put them in a stranger’s home, and then you retraumatize them.”

This is a particular concern for Indigenous children, who have suffered disproportionate removal from their families and forced cultural assimilation over generations.

“What hits me and hurts my heart the most is that we have another generation of children that potentially are not going to be connected to their culture,” said Danica Love Brown, a behavioral health specialist and member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Brown is vice president of behavioral health transformation at Kauffman and Associates, a national tribal health consulting firm.

“We do know that culture is healing, and when people are connected to their culture … when they’re connected to their land and their community, they’re connected to their cultural activities, the healthier they are,” she said.

Ana Beltran, an attorney at Generations United, which supports kin caregivers and grandfamilies, said large families still often need money and counseling to take care of orphaned children. (UNICEF defines an orphan as a child who has lost at least one parent.) She noted that multigenerational households are common in Black, Latino and Indigenous families.

“It can look like they have a lot of support because they have these huge networks, and that’s such a powerful component of their culture and such a cultural strength. But on the other hand, service providers shouldn’t just walk away because, ‘Oh, they’re good,’” she said.

Counties with higher overdose death rates were more likely to have children with grandparents as the primary caregiver, according to a 2023 study from East Tennessee State University. This was particularly true for counties across states in the Appalachian region. Tennessee has the third-highest drug overdose death rate in the nation, following the District of Columbia and West Virginia.

‘Get well’

AmandaLynn Reese, chief program officer at Harm Reduction Ohio, a nonprofit that distributes kits of the opioid-overdose antidote naloxone, lost her parents to the drug epidemic and struggled with addiction herself.

Her mother died from an overdose 10 years ago, when Reese was in her mid-20s, and she lost her dad when she was 8. Her mom was a waitress and cleaned houses, and her dad was an autoworker. Both struggled with prescription opioids, specifically painkillers, as well as illicit drugs.

“Maybe we couldn’t save our mama, but, you know, somebody else’s mama is out there,” Reese said. “Children of loss are left out of the conversation. … This is bigger than the way we were seeing it, and it has long-lasting effects.”

In Ohio, Emma’s grandmother started a small shop called Nina’s Closet, where caregivers or those battling addiction can come by and collect clothing donations and naloxone.

Emma, who helps fill donation boxes, tells her grandmother she misses the scent of her mom’s hair. She couldn’t describe it, Hamilton said — just that “it had a special smell.”

And in an interview with Stateline, Emma said she wants kids like her to have hobbies — “something they really, really like to do” — to distract them from the sadness.

She likes to think of her mom as smiling, remembering how fun she was and how she liked to play pranks on Emma’s grandfather.

“This is what I would say to the users: ‘Get treatment, get well,’” Emma said.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: [email protected]. Follow Stateline on Facebook and X.

]]>Cleanup efforts at the Isom IGA store in East Kentucky after the flooding of July 2022. (Photo by Malcolm Wilson)

This story was produced through a collaboration between the Daily Yonder, which covers rural America, and Climate Central, a nonadvocacy science and news group.

On the day he would become homeless, Wesley Bryant was awoken by his wife, Alexis.

“Get up,” she told him. “There’s a flood outside.”

It was 8 a.m. on a Thursday in late July, two years ago in rural Pike County, Kentucky, and rain had been pouring for days. Overnight, it got heavier. Homes and vehicles were being swept down the narrow valleys of Eastern Kentucky’s mountainous terrain.

Dozens of people died after more than a foot of rain fell from July 26 through July 30, 2022, flooding 13 rural counties in Eastern Kentucky. Yet as these communities attempt to rebuild, they’re being overlooked for federal spending that’s protecting wealthier and more urbanized Americans from such weather disasters.

Wesley, Alexis, their two daughters and Alexis’ sister evacuated, hiking the half-mile to Alexis’ mother’s house via the mountains behind their own home to avoid flooded roads. They’ve been living there ever since.

Kentucky is a regular victim of flooding. During the past century, more than 100 people have died in storms across the state, including at least 44 two summers ago. Heat-trapping pollution is driving up rainfall rates and flood risks.

Thousands of survivors were forced to move out of damaged homes, including Wesley and his family. Their house, which Wesley’s grandfather built in the 1970s, is unlivable. Insulation peels from the ceiling and the floors bubble with water damage. Finding contractors to fix the house has been difficult because thousands of other flooded properties are also being repaired or replaced.

Their furniture and appliances were destroyed, and Wesley estimates replacing them would cost around $20,000. The family was denied FEMA disaster assistance so they’ve had to foot these costs themselves. “We just need a little help from our government,” he said.

Despite histories of flooding, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) classifies Pike County and the 12 other counties that flooded two years ago as facing “low” risks in the event of a natural disaster like a flood. That’s largely because they have less to lose —financially — compared to more urbanized areas.

Critics of FEMA’s risk-determination tool, called the National Risk Index, say it doesn’t include enough information about rural communities, especially when it comes to flooding, leading it to understate hazards.

That suggests that as the federal government cranks up spending on infrastructure, including the allocation of more than $1 billion to help reduce future flood threats, families in East Kentucky and other rural regions are at risk of missing out on projects that could help them prepare better for the next disaster.

What is the National Risk Index

FEMA developed its National Risk Index to help local and state officials and residents plan for emergencies through an online tool. The agency sourced historic rainfall and other data to characterize these risks, allowing it to paint a national picture of threats from local disasters, findings that influence its spending decisions.

FEMA began developing the risk index in 2016, though initial work dates to 2008. The first iteration of the risk index was released in October 2020, and the data has been updated twice since then, most recently in March 2023.

Work to update how the risk index handles inland flooding is expected early next year. In a press release touting new requirements that forced the coming update, the Biden administration said that in “recent years, communities have seen repeated flooding that threatens both lives and property” but that the agency’s approaches to measuring risks based on historical data “have become outdated.”

The agency is also working on a “climate-informed” risk index looking at future hazards but, so far, inland flooding is not on the list of disasters planned to be included.

FEMA’s national and regional press offices declined to be interviewed or answer questions for this story.

“There’s a bias against, I think, rural communities, especially in the flood dataset,” said Chad Berginnis, executive director of the Association of State Floodplain Managers, a nonprofit that certifies floodplain managers and educates policymakers about flood loss. He said this bias could profoundly confuse or affect emergency managers in those areas.

“It’s giving false results,” Berginnis said. “I think we’ve got to be very thoughtful and very careful on how we use [the risk index] for the hazard of flood in particular.”

The building of homes and communities in vulnerable locations and the effects of heat-trapping pollution are converging to escalate the frequency of weather disasters across the U.S. One of the effects of climate change is an intensification in the amount of rainfall that can fall every hour. A federal report on the latest climate science showed the rainiest days across the Southeast are dumping more than a third more water on average now than was the case in the late 1950s. Ongoing emissions and warming threaten to continue to boost rainfall rates.

“If it’s gone up that much already, we might be wise to be concerned,” said Scott Denning, an atmospheric sciences professor at Colorado State University who studies carbon dioxide, water, and energy cycles. “You ain’t seen nothing yet.”

That rain often falls on ground where coal mining excavations removed mountaintops. Researchers overlaid data regarding fatalities from the floods with maps of mountaintop removal mining and found that many of the deaths were downstream from or adjacent to such sites.

Neglecting rural Americans

Todd DePriest doesn’t “believe in Facebook,” but uses his mother’s account to surf the website’s digital marketplace. That’s what he was doing two summers ago when he saw alerts about severe floods in Letcher County, Kentucky, where he serves as the mayor of Jenkins, population 1,800.

Public service announcements warning people to “turn around, don’t drown” during floods were circulating on his mother’s feed. DePriest got up from his computer to look out the window at the torrential rain and realized the threat his own town was about to face.

DePriest jumped in his Jeep to check on the bridge at the lower end of Jenkins. When he got there, the road across the bridge had already flooded.

“I started calling people I knew down there and said, ‘Hey, the water’s up and if you want to get out of here, we’re going to have to do something pretty quick,’” DePriest said.

His next calls were to the fire department to prepare them for the emergencies to which they were likely to respond, then to city workers to get essential maintenance vehicles like garbage trucks to higher ground.

Letcher County was one of the hardest hit of the 13 counties declared federal disaster areas by FEMA. Five of those killed across the region were in Letcher County.

Two years since the floods, the region is still rebuilding. “They (FEMA) were telling us it was going to take four or five, six years to recover and get through this,” DePriest said. “And I thought, well, there’s no way it’s going to take that long.”

Now, DePriest hopes it only takes five years.

“All the processes and dealing with FEMA – and I think they’re fair in what they do – but it’s just a process,” DePriest said.

The National Risk Index multiplies a community’s expected annual loss in dollars by their risk factor. Like most of the east Kentucky counties that flooded two summers ago, Letcher County’s risk level is scored “very low” by the risk index.

That’s because it includes annual asset loss in its equations.

Rural counties like Letcher, where the average home costs about $75,000 and median household income is half the national average, score lower on the risk scale because there are fewer dollars to lose when disaster strikes. The area’s flood hazard threat is deemed relatively high but the potential consequences in financial losses are lower compared with denser areas.

The urban-rural disparity can be examined by comparing how the National Risk Index judges Jackson, Kentucky, a small city about 80 miles southeast of Lexington, with Jackson, Mississippi, the Magnolia State’s populous capital.

Both cities saw disastrous flooding during the summer of 2022. Unlike its namesake in Kentucky, Jackson, Mississippians suffered no flood deaths, though financial damage was far worse —?an estimated $1 billion.

Hinds County – home to Mississippi’s capital – is assigned a “relatively moderate” risk level. Its social vulnerability is categorized as very high, with community resiliency categorized as relatively high, meaning the community is expected to bounce back more effortlessly after disaster. River flooding is deemed the second greatest natural disaster risk, with annual losses estimated at about $15 million.

To compare, Breathitt County, where Jackson, Kentucky, is located, is given a “very low” risk level by the National Risk Index. Its social vulnerability is categorized as relatively high and community resiliency is categorized as very low, suggesting it would need more help after disasters. Although FEMA considers river flooding the greatest disaster risk to the community, its annual losses are rated at just $1.3 million.

This urban-rural difference matters because FEMA uses the National Risk Index to determine how much money communities should receive to better prepare for natural disasters. For example, it’s being used to make decisions about spending $1.2 trillion available to lessen future flood risks under the U.S. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

The risk index is also used to determine which communities get money through FEMA’s Community Disaster Resilience Zones program, which designated 483 community census tracts as Community Disaster Resilience Zones last year. This means the communities inside those tracts can receive extra money for disaster planning. Of those census tracts, a third are federally classified as rural.

Disaster experts say relying solely on the risk index can disadvantage places that lack long-term weather records — which are often missing from rural communities.

Weather stations can be sparse in treacherous landscapes. Rural areas are among the last to have their flood hazards mapped by FEMA, with the agency prioritizing higher-density regions. And National Weather Service offices tend to be located in more urban areas, according to Melanie Gall, co-director of the Center for Emergency Management Homeland Security at Arizona State University.

“I think that we miss a lot,” she said.

Progress post-flood

Immediately after the July 2022 floods, FEMA and Kentucky Emergency Management began temporarily providing trailers for hundreds of flood survivors. Both programs have since ended.

FEMA gave trailer occupants the option to purchase their units as permanent housing. The trailer cost was determined by a formula that factored the type of unit, its size, and how many months it had been occupied by the interested buyer.

In the middle of the most recent winter, 18 months after torrential rainfall on steep slopes left so many families homeless, federal trailers that hadn’t been paid for were hauled away.

Kentucky’s program offered more flexibility: While the program has ended, three families still live in state-funded campers, according to Julia Stanganelli, flood recovery coordinator for the Housing Development Alliance. The Eastern Kentucky-based affordable housing developer has led the efforts to rehab and rebuild houses lost in the flood using state disaster money.

The three families are living in the campers while they wait for a new housing development to be built above the floodplain in Knott County, Kentucky, Stanganelli said.

East Kentucky’s population was declining long before the floods. Shaping Our Appalachian Region, a nonprofit focused on population retention and growth, estimates Eastern Kentucky has lost nearly 55,000 residents since 2000. The floods accelerated the losses.

During the 2022 floods, already sparse cell service went out entirely, and even the U.S. Weather Service’s on-duty warning meteorologist faced busy or disconnected phone lines, recalls Jane Marie Wix, a warning coordination meteorologist with the Weather Service.

Wix said the creek near her house turned into a “river,” preventing her from reaching work. “I don’t think I’ve ever felt so helpless before.”

Locals are working to better prepare for the next disaster, with or without federal government help.

Todd DePriest, the mayor of Jenkins, worked with the nonprofit law firm Appalachian Citizens Law Center to pay for four stream monitors that can trigger flood warnings.

Wesley Bryant, the Pike County resident whose home flooded two years ago, said he’s called his state representatives “hundreds of times” to keep Eastern Kentucky’s disaster recovery top of mind.

Bryant said he recently felt “pretty defeated” after receiving another notification about failing to qualify for federal assistance. But he said he won’t quit fighting.

“This is my home, this is my commonwealth,” Wesley said. “I’m going to fight for it.”

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

The U.S. Department of Agriculture will pay a total of about $2 billion to farmers across the U.S. who were victims of discrimination. (Stock photo by Preston Keres/USDA/FPAC)

Tens of thousands of farmers or would-be farmers who say they suffered discrimination when they applied for assistance from the U.S. Department of Agriculture will get one-time payments that total about $2 billion from the federal government.

“While this financial assistance is not compensation for anyone’s losses or pain endured, it is an acknowledgement,” U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said Wednesday in a call with reporters.

The payments are the result of a program — the Discrimination Financial Assistance Program — created by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 that was meant to aid farmers, ranchers and forest landowners. President Joe Biden said it was the result of his promise “to address this inequity when I became president.”

The USDA received more than 58,000 applications from people who claimed discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, age, marital status, disability and retaliation for “civil rights activity.”

Vilsack could not immediately say what type of discrimination was most often indicated by the applicants, but the bulk of the payments went to farmers in southern states with higher percentages of Black residents.

Payments were awarded to people in every state and three of its territories, but residents of Alabama and Mississippi alone received almost half of the money.

In Kentucky, 75 recipients will share in $4.4 million.

More than 43,000 people will be paid, Vilsack said. The payments range from $3,500 to $500,000, depending on the circumstances and effects of the discrimination.

The department could not immediately supply a summary of those claims, but Vilsack said the discrimination resulted in loan denials, loan delays, higher interest rates and an overall lack of assistance.

“We’ve made significant strides in breaking down barriers to access, and my hope is that people will begin to think differently about USDA, so that we can better serve all who want to participate in agriculture in the future,” Vilsack said.

Specifically, Vilsack said the department’s Farm Service Agency, which administers farm loans, now has a more diverse leadership and loan assessment processes that rely less on human discretion.

This story republished from the Iowa Capital Dispatch, a sister publication to the Kentucky Lantern and part of the nonprofit States Newsroom network.

]]>Next to the Wayland Area Volunteer Fire Department in Floyd County are 11 new homes, outside the floodplain. (Photo by Al Cross/Kentucky Lantern)

WAYLAND, Ky. – Gov. Andy Beshear promised a different future for Eastern Kentucky as he made five stops in the region Friday to signal the weekend’s second anniversary of record floods on the night of July 27-28, 2022.

In the little Floyd County town of Wayland, Beshear dedicated 11 homes that he said would be the first “fully inhabited” new development on “high ground,” above the mountainous region’s often-flooded streams.

In the Knott County seat of Hindman, he paid tribute to the flood’s 45 victims, 22 of whom were in Knott, after announcing that the state had bought more than 100 acres for 150 homes on a reclaimed surface coal mine — a dream decades old and finally made possible by the flood’s existential challenge to the region.

“That makes it official,” Beshear said at the Chestnut Ridge development next to the Knott County Sportsplex on Kentucky 80. “This project is happening.” An adjoining tract with 50 homes will be developed by the Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky and its partners, and another high-ground community, Olive Branch tear Talcum, is in the works.

We knew with the infrastructure that was destroyed, with the thousands of people who were left homeless, this was probably the most difficult rebuild in the history of the United States. But it happened to the toughest of people. And immediately what we saw was the best of our humanity.

– Gov. Andy Beshear

Another is coming above Hazard in Perry County, where Beshear announced financing for completion of a road to serve the new 50-acre Sky View subdivision, which will make possible an adjacent private development that Hazard’s mayor says would be the region’s largest housing development.

And in Jackson, he announced $6 million in state aid to build 20 homes for flood survivors and said the state continues to look for a large tract for homes on high ground in Breathitt County, which has one of the nation’s highest unemployment rates and is officially estimated to have lost more than 5% of its population since 2020.

“I want people to stay here,” Beshear said, “but you know what? I want people to move here. It’s time for Eastern Kentucky to get its share.”

At Sky View, he said local and state officials “are going to bring hundreds and thousands of new jobs to Eastern Kentucky.” He also pledged, “This fall and this winter you are gonna see those homes start coming up.”

That will be welcome in a region that has heard more talk than action aimed solving its problems, Perry County Judge-Executive Scott Alexander told Beshear and the crowd:

“Governor, far too often, the people of East Kentucky and Appalachia have heard promises from government, only for those to never be followed through. And so I really believe that more and more people will start believing in what we’re doing as they can see the progress happening.”

Tangible progress

The progress was tangible in Wayland, as several families getting new homes in a narrow strip next to the local fire department dedicated the homes with Beshear and officials of the Appalachia Service Project, a faith-based nonprofit that brings volunteers from all over the nation to the region.

“It’s remarkable, the amount of work that’s gone on to make sure these people get back on their feet,” Floyd County Judge-Executive Robbie Williams told the crowd.

One new homeowner is Jackie Bradley, 71, who has been living in an apartment in Martin, where the forks of Beaver Creek meet. Wayland is a few miles upstream, at Right Beaver’s confluence with Steele Creek. She had lived in Glo Hollow, just downstream from Wayland, so close to the creek that her home was flooded twice — the second time a few days after the first, when rains swelled Right Beaver again and her house was caught in a whirlpool. She said her 6-year-old grandson yelled, “Granny, look at your house! It’s like the Wizard of Oz!”

Beshear said repeatedly that the favorite part of his job has been seeing young children go through their new home, picking out their bedrooms. “You just see a little bit of God in that moment,” he said in Wayland.

The Appalachia Service Project plans to build about a dozen more homes in or near the town of 400. Materials are already stored across the road from the new homes, waiting on identification of properties and negotiations for acquisition.

‘Living out the Golden Rule’

State government and other entities helped with the infrastructure for the 11 homes. The Federal Home Loan Bank helped the state with construction financing. “We loan money to banks, but we set aside 15% of our profits for affordable housing,” FHLB of Cincinnati President Judy Rose told the crowd. She said ASP and Beshear have been leaders in “getting boots on the ground” to do the work.

Beshear said the many volunteers are “living out the Golden Rule that we are to love our neighbor as ourself, and the parable of the Good Samaritan that says everyone is our neighbor. In a world that sometimes feels toxic, that we’re supposed to be against each other, you all have come together as one people to truly stand up for each other and to house those that have lost everything.”

Other high-ground developments are in Letcher County: Grand View near Jenkins, which is to have 116 homes on 92 acres, and The Cottages at Thompson Branch near Whitesburg, with 10 homes, one of them already occupied.

Beshear said there may be more: “There’s a couple of others [where] we’re still trying to work through issues.”

He told reporters in Wayland, “We’re more than halfway through because the toughest part that takes the longest are the utilities. … We knew with the infrastructure that was destroyed, with the thousands of people who were left homeless, this was probably the most difficult rebuild in the history of the United States.

“But it happened to the toughest of people. And immediately what we saw was the best of our humanity. It was people pushing aside all the silliness, not caring if somebody’s a Democrat or a Republican, just caring that they are a human being, wanting to get them back on their feet. You saw Kentuckians living for each other, and that Eastern Kentuckians are as tough as nails, and as kind as anybody else out there on planet Earth.”

The Democratic governor said state agencies “worked together in ways we’ve never seen, doing things that were never done.” Officials of the Energy and Environment Cabinet have essentially become land developers, because they have to make sure that the reclaimed mine sites are stable and properly drained.

“We’ve never done anything like this,” Beshear said of state employees. “Their level of dedication, the work they’ve put in while doing their day job, has been really special. I’ve seen amazing leadership from people who may have been in state government almost all of their lives but see this as the most important thing that they’ve done in serving the Commonwealth of Kentucky.”

As it gets into the land-development business, the state is also negotiating with landowners like Paul Ison of Hazard, who donated 50 acres to the state for Sky View but will soon be in a position to profit from developing about 200 adjoining acres.

By building the access road to Sky View, Ison said, “They’re helping the whole community out. You gotta have housing to get another factory or some more business here.”

Beshear said in an interview, “I believe that Paul Ison was very generous. We asked for as much as he would offer, and 50 acres is where he started, and it was more than enough for what we needed. … It’s a good deal for everybody. We can’t build enough just through nonprofits to address overall housing needs, so I welcome private development.”

This story has been updated to clarify that the Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky and its partners are developing a 50-home tract near the Knott County Sportsplex and also the Olive Branch community near Talcum. An earlier version had incorrect information.

Al Cross is director emeritus of the Institute for Rural Journalism. After more than 50 years of reporting and editing, he says the trip with Beshear was probably his last for a news story. He retires Aug, 1.

]]>Local grocery stores and pharmacies struggle to compete with dollar stores but rural residents view the chain stores positively. (Ohio Capital Journal photo by Graham Stokes)

The influx of dollar stores into the rural landscape can have a devastating effect on grocery stores and other small businesses in rural areas, research has found.

When dollar stores move into a rural area, independent grocery stores are more likely to close, says a new study released by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Employment and sales fall at grocery stores wherever a dollar store is located, the researchers found, but in rural areas the effects are more profound.

“They’re going after the low hanging fruit… when it comes to being able to capture consumer sales,” Kennedy Smith, senior researcher with the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR), said in an interview with The Daily Yonder. “These are the communities that tend to be too small for a Walmart to have been there, but small enough that if there was a major grocery store chain there at some point, it’s probably gone now. They see an opportunity.”

The proliferation of dollar stores in rural areas is not an accident, Smith said. In ILSR’s 2023 report, The Dollar Store Invasion, researchers said dollar stores are more likely to be located in low-income and rural areas.

The likelihood a rural grocery store would exit the area after a dollar store moves in was three times greater than in an urban area, the USDA researchers found. Rural grocery stores saw nearly double the decline in sales (9.2%) than urban grocery stores, and saw bigger decreases in employment (7.1%). The researchers also found that in urban areas, the impact of a dollar store waned after about five years, but the effects latest longer in rural areas.

Two companies – Dollar General and Dollar Tree — own most of the dollar stores across the country, with Dollar Tree also owning all of the Family Dollar stores. Over the last four years, Dollar General has added about 3,500 locations, bringing to 18,000 the number of locations for the chain, and cementing the company’s status as the largest retailer in the U.S, according to the ILSR report.

And the number of dollar stores across the country has grown over the past two decades. Between 2000 and 2019, the study found, the number of dollar stores – including Dollar Tree, Family Dollar and Dollar General – has doubled to more than 34,000. However, earlier this year? Dollar Tree announced plans to close 1,400 of its 16,700 stores due to corporate losses in 2023. Even after those closures, there will be more dollar stores than all of the Walmarts, Targets, McDonalds and Starbucks in the U.S. combined.

ILSR’s Smith said that the companies chose places where they feel there will be little pushback to the stores opening.

“I think that they are a little predatory in choosing places where they think that political resistance is going to be weak and where it’s easy for them to come in and request that a piece of land be rezoned for commercial purposes and not get a lot of blowback from the community,” Smith said.

Kathryn J. Draeger, adjunct professor of agronomy and plant genetics at the University of Minnesota and statewide director of the university’s Regional Sustainable Development Partnerships, said dollar stores don’t just affect grocery stores.

“It’s not just the grocery stores that are hurt when a dollar store comes in,” Draeger said in an interview with the Daily Yonder. “We’re also hearing that pharmacies can suffer because, instead of getting Tylenol and cough medicine at your pharmacy, you’re getting it at the Dollar Store, and that is cutting into the business of small town pharmacies as well.”

Dollar stores also affect sales at small town hardware stores, pet stores and other retailers, she said. The closure of a small town grocery store can impact the culture of a community, she said.

“Grocery stores are part of the heart and soul of a community,” Draeger said. “It is such a hub in the community for people to connect and talk with each other. These small town stores, yes, they’re private businesses, but they do so much public good.”

Dollar stores can have a positive impact in communities, though. In a 2022 study from the Center for Science in the Public Interest, dollar stores are generally viewed by residents to provide access to food in food deserts.? To gauge the public perception of the stores, the CSPI surveyed 750 residents who live near dollar stores and have limited incomes.

“Most survey respondents (82%) indicated dollar stores helped their community,” the CSPI survey found. “Overall, dollar store chains were viewed favorably, ranking third after big box stores and supermarkets, but ahead of convenience, small food, and wholesale club stores.”

Additionally, non-profit work by the corporations give back to the communities they are in. Dollar General Inc.’s non-profit foundation, the Dollar General Literacy Foundation, provides grant funding to literacy and education initiatives at schools, libraries and other non-profit organizations near its stores. Dollar Tree also participates in community giving by partnering with dozens of charitable organizations across the country, including Operation Homefront, the Boys & Girls Clubs of America, and United Way of South Hampton Roads near the company’s corporate headquarters in Chesapeake, Virginia.

Still, researchers found, some local communities are working to keep the stores out. According to CSPI, more than 50 communities across the country have passed ordinances to “ban, limit, or improve new dollar stores in their localities.”

ILSR’s Smith said one thing communities can do to prevent the intrusion of dollar stores is to work with county planning and zoning commissions to stop the spread of the stores. From assessing traffic issues to addressing water table problems, communities can stop dollar stores from coming into communities and causing harm, she said.

By supporting local grocery stores instead of larger chains, Smith said, community leaders and elected officials can keep profits generated by those stores in the community instead of heading out of state to corporate headquarters. Supporting the local stores also supports good wage jobs, local families and economic development. Like the closure of a rural hospital, she said, the closure of a rural grocery store can impact a community’s ability to attract new people and new businesses to the area.

Rial Carver, program director for the Rural Grocery Initiative at Kansas State University, said it’s not just dollar stores that cause the exit of rural grocery stores.

According to research by RGI, one in five rural grocery stores closed between 2008 and 2018. In half of the 105 Kansas communities that lost grocers, no new store had opened up by 2023.

“Rural independent grocery stores are facing a myriad of challenges and those have been building for years,” she said in an interview with the Daily Yonder. “When a dollar store comes in, those challenges come to a head.”

Aging infrastructure, population decline, aging equipment and older technology add to the hurdles rural grocery stores face to succeed.

“They are less able to take advantage of new programs like SNAP and online ordering,” she said. “Dollar stores can come in and be the last straw facing a rural grocery. It’s not a foregone conclusion that rural groceries will close when a dollar store comes into the community, but it can be harder for a small, independent grocery store to adapt to face yet another challenge.”

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

A medical student at work. (UK photo)

The University of Kentucky College of Medicine and Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield Medicaid in Kentucky are giving medical students on a path to serve rural areas seven scholarships worth $100,000 in total.?

Fourth year students in UK’s Rural Physician Leadership Program will benefit from this money, UK said. They need to demonstrate financial need and intend to practice medicine in a rural area.?

RPLP students start their medical school journey in Lexington at the college’s main campus and then spend two years in Morehead rotating in rural clinics. The 10-year-old program’s goal is to graduate physicians who are culturally competent to treat rural patients. Since its launch, 110 doctors have graduated from this program.?

“This generous gift will equip more mission-driven students with the training to become doctors who can fulfill vital health care needs in rural communities,” UK College of Medicine Dean Dr. Charles “Chipper” Griffith III said in a statement.?

Funneling more physicians into rural areas is important to tackling the state’s dismal health outcomes, he added.??

Kentucky suffers from a lack of primary care providers. The Kentucky Primary Care Association said in 2022 that 94% of the state’s 120 counties don’t have enough primary care providers, the Lantern previously reported. And the commonwealth is one of the? sickest overall states in the nation.?

“This effort helps guarantee the availability of high-quality care in every corner of the state, particularly in our rural and underserved communities where the need is most pronounced,” said Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield Medicaid in Kentucky President Leon Lamoreaux.?

Of its more than 100 graduates, half of the physicians who graduated from the RPLP program went into primary care, UK said. Most students who enter the program come from underserved areas, according to UK, “and have a strong desire to make a difference in communities that need greater health care access.”?

The first of the Anthem Rural Medicine Scholarships will be announced in March on Match Day, UK said. On Match Day, medical school students learn where they matched for their post-graduation residencies.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

(Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

The percentage of rural households experiencing food insecurity grew by 4 points in 2022 to 15%. Metropolitan households experiencing food insecurity grew by 2 points to 12%.

The rate of increase was nearly two-thirds greater in rural areas than in metropolitan ones, according to data from Food and Nutrition Service (FNS).

The increase was expected because of the end of pandemic-era nutrition program expansions. But the spike surprised staff at the nonprofit Food Research and Action Center (FRAC).

“The difference between metro and nonmetro areas is even bigger than it was before [the pandemic],” Geri Henchy, FRAC’s director of nutrition policy, told the Daily Yonder.

The increasing gap between rural and urban food insecurity suggests that rural communities are struggling to bounce back from pandemic challenges more than their urban peers.

Food insecurity is related to chronic nutrition problems and is defined as a lack of consistent access to enough food for everyone in a household to live an active and healthy life.

Data from FNS 2021 showed that food insecurity decreased during the first year of the pandemic as emergency roll outs helped struggling households put food on the table.

But for many years before the pandemic, a greater share of rural households experienced food insecurity compared to their urban counterparts. The only time metro rates were higher than rural rates was during 2008 and 2009, when the Great Recession made food insecurity increase nationwide.

From 2014 to 2021, however, food insecurity declined in both rural and urban areas. But when Congress rolled back pandemic-era benefits at the end of 2021, food insecurity rates grew faster in rural communities than urban ones.

Cutting federal programs makes child poverty and food insecurity worse

One of the many things pandemic-era benefit programs did was provide all children in public schools with free meals. This program and others like it have been rolled back since April of this year when the Biden administration declared the end of the national pandemic emergency.

“Even if you’re paying [for school meals] at a reduced price, it really adds up,” Henchy said. “If you’re a family that’s struggling and can’t pay that, then your kids end up being embarrassed at school.”

At the end of 2021, Congress also allowed the expiration of the expanded child tax credit. The credit cut child poverty in half during the first year of the pandemic. But new census data shows that child poverty doubled after the expansions ended.

“You don’t get the [expanded] child tax credit anymore. You don’t get healthy school meals for all anymore,” Henchy said. “Things just started getting harder and we’re starting to see more people at the food pantries again, and people are hungry.”

One thing that didn’t revert to former practices with the end of the pandemic provisions? is that the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) nutrition program permanently changed how they conduct certification appointments. Participants can now attend appointments remotely, something helpful for rural residents who, on average, have less reliable transportation than their urban counterparts.

“WIC is a really great buffer against the harmful impacts of economic hardship,” but the program is underfunded, Henchy said.

Congress needs to fully fund WIC in the continuing resolution that needs to pass by November 17 to stave off a government shutdown, she said. If Congress can’t provide adequate funds, WIC is “going to be forced to turn people away,” she said.

“WIC has such a long history of bipartisan support.? It’s just kind of stunning that suddenly this relatively small group of people in Congress can oppose fully funding WIC when everyone else wants to take care of it.”

SNAP cuts and higher cost of living exacerbate food insecurity

When the federal pandemic emergency declaration ended, Congress also reinstated work requirements for people receiving benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps. After three months of consecutive benefits, able-bodied adults without dependents must work 80 hours per month to continue receiving SNAP. These work requirements may be particularly challenging for rural residents who have to travel longer distances to get to work.

“We know that people are trying to find a job,” Henchy said. “The thing is that there aren’t any jobs [in rural areas]. If you impose a work requirement like that in a situation where there just aren’t enough jobs, what you are saying to people is that they’re not gonna be able to stay on SNAP no matter what they do.”

Henchy also suggested that increases in cost of living and associated supply chain issues disproportionately hurt rural communities because they deal with both longer distances to grocery stores and higher fuel prices.

Henchy said that the higher number of rural residents who receive SNAP and the transportation challenges exacerbated by higher costs of living can make rural areas more vulnerable to economic hardships.

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear embraces then-Rep. Angie Hatton as Whitesburg Mayor Tiffany Craft speaks to the media on July 31, 2022 in Whitesburg. At that time, 28 people had been identified as killed in flooding in southeastern Kentucky; the number rose to 45. (Photo by Michael Swensen/Getty Images)

Rural voters were part of a statewide shift toward incumbent Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear this week, helping give the Democrat a 5-point election victory in a state that Donald Trump won by over 25 points three years ago.

Beshear won the statewide vote 52.5% to 47.5%, a comfortable margin compared to his 2019 election victory of 0.4 points.

Beshear did 2.4 points better with rural voters this year compared to 2019 (see the graph at the top of the story). He still lost among rural voters, 43.3% to 56.7%, to Republican challenger Daniel Cameron. But with less of a rural deficit, his advantage in other parts of the state more than made up the difference.

Beshear won 17 of Kentucky’s 85 rural (nonmetropolitan) counties this year, compared to 13 in 2019. The Democrat flipped five rural counties, while his challenger flipped one rural county back to the Republican side.

Beshear also flipped three metropolitan counties. Two were in outlying counties of the Lexington metro, and one, Daviess County, is the central county of the Owensboro metropolitan area. Republican Cameron flipped Hancock County, also part of the Owensboro metropolitan area.

The Kentucky governor’s race drew national attention as a test of whether a Democratic candidate could hold a state that supported Trump so strongly in 2020.

During his first term, Beshear has focused on traditional Democratic issues like infrastructure and investment. He mentioned new road construction in his victory speech Friday night.

The governor’s handling of the catastrophic 2022 flood in Eastern Kentucky may have been a factor with some voters. The disaster killed 45 people and destroyed and damaged thousands of homes in East Kentucky.

The seven counties that gave Beshear his largest percentage-point increase compared to 2019 were all affected by the flooding. Two of the hardest hit, Letcher and Perry, flipped from Republican to Democratic. Beshear lost those counties by 9 points in 2019. After recovery efforts that included several gubernatorial visits, Beshear won Letcher by 5 points and Perry by 11.

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

From left, Robyn Pizzo, Sherman Neal and Shelly Baskin, who campaigned for removal of a Confederate monument from the Calloway County Courthouse grounds, display some of the yard signs that sprouted across the community. The fiscal court decided to leave the statue of Robert E. Lee where it has stood since 1917. (Photo Courtesy of Rural-Urban Exchange)

Sherman Neal spent many days of the summer of 2020 in the Western Kentucky college town of Murray next to a Confederate monument at the county courthouse.?

It was on the heels of the murder of George Floyd and the fatal police shooting of Breonna Taylor when Neal — a Black volunteer college football coach, veteran and recent transplant to the city — penned an open letter to local leadership calling for the monument to be removed.?

In that letter, he evoked his young children, saying if they asked about the monument, he would have to tell them it was a racist symbol put in place “to keep Black people quiet and subservient.” The monument, which features a statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee, was erected with funds from a local United Daughters of the Confederacy chapter in 1917.?

Neal’s letter sparked a movement that led to months of protests, a local man assaulting protesters with mace and a march on the county courthouse square, a place where those wanting the monument to stay often confronted those who wanted it removed.

“You don’t get too many opportunities in life to go through real shared hardships together and learn lessons at the same time,” Neal said in a recent interview with the Lantern. “It takes actual experience sometimes to learn certain things and build certain bonds.”?

A new documentary, “Ghosts of a Lost Cause,” captures the struggles and bonds built by those in Murray who pushed for the monument to be removed.

It is one of a series of documentaries airing this Saturday in communities across Kentucky, coinciding with a regional tradition of celebrating emancipation from chattel slavery on Aug. 8.?

The Rural-Urban Solidarity Project, coordinated by the organization Kentucky Rural-Urban Exchange, is airing four films that chronicle actions and protests for racial justice that Kentuckians took following the killing of Breonna Taylor, while also uplifting and celebrating Black communities across the state.?

Robyn Pizzo, a resident featured in the Murray documentary, made “Move the Monument” yard signs that sprouted across the community. She said watching the film is “painful” and “heartbreaking” in some ways given that advocates, like herself, for removing the Confederate monument didn’t achieve their goal.?

Lee’s statue remains by the county courthouse after the Calloway County Fiscal Court decided to keep it on county property in 2020. But the bonds made between Pizzo, Sherman and other community members throughout those efforts also remain.?

“I think some of the power in the storytelling is the diversity of the people who were interviewed and the people who were part of the movement, like the backgrounds that we all came from, our motivations to join, how it’s impacted our lives since,” Pizzo said. “I think that there is a hope, that even individual people making small changes can have an impact to the future of what Kentucky looks like and making it a more welcoming and equitable place for everyone.”

Years in the making

Savannah Barrett, the co-founder of the Kentucky Rural-Urban Exchange, is still deeply connected to her roots in Grayson County.

Barrett helps lead the Exchange, an organization that brings together Kentuckians from rural and urban communities to share ideas and create understanding and bridge divides.?

When people began to fill the streets of her current home in Louisville following the police killing of Breonna Taylor, she was also hearing from people she knew about Black Lives Matter protests popping up in smaller communities across the state, including in her home of Grayson County.?

She saw that younger people in Leitchfield, the Grayson County seat, were organizing a protest at a local courthouse.?

“I can say without a shadow of a doubt that that has never happened in Leitchfield,” Barrett said.?

She said she recognized the protests sweeping across rural communities in solidarity with Black Kentuckians was something “very special,” and working with filmmakers she knew, efforts began to capture some of those moments on film. The ideas for the documentaries were conceived from that footage.?

“We started to work with our member network to try and figure out how to make these films in a way that was by and for the folks who were supporting these actions across the state,” Barrett said. “We needed to hear from more Black Kentuckians. We needed the leadership and oversight of some of the luminaries in African American arts and culture in the state.”

As the ideas for the films progressed, she reached out to people such as Betty Dobson who runs the Hotel Metropolitan, a storied hotel-turned-museum in Paducah that hosted Black travelers including stars such as James Brown and Louis Armstrong during the era of segregation. A documentary highlighting Hotel Metropolitan’s history and the importance of preserving and sharing Black history, “Preserving the Past to Build a Better Future,” became one of the films in the series.?

Barrett said the films are purposefully being shown around when gatherings take place for Black communities in Kentucky, specifically the Old Timers festival in Covington and the Eighth of August emancipation celebrations in Western Kentucky. The film in Harlan County is also dedicated in the memory of two people featured in the documentary who have since passed away.

“It just felt right,” Barrett said.?

Other documentaries that came into shape include “Words I Speak: Solidarity + Resiliency,” featuring stories of Black women leaders from Northern Kentucky who stepped up to organize their community or run for office.

Another film being showcased in Harlan County highlights the Eastern Kentucky Social Club, a treasured gathering space and far-flung network of friends and family. The film also details the challenges and resilience of Black people in the mountain county.

“We looked at different stories,” said Gerry James, one of the filmmakers involved with the documentaries. “We wanted to have diverse geography.”

James was particularly involved with the production of the film in Murray. The story of Sherman Neal and his struggles to remove the monument personally resonated with James, who is also Black. James works in outdoor recreation planning and recounted a story of visiting downtown Glasgow in southern Kentucky to help build a trail.?

“I pulled up to downtown Glasgow, and I parked right in front of a Confederate monument. And then a Black family walks past,” James said. “It just reminded me of myself in that moment and how I felt about that monument.”

James said he wanted to show the “humanity” of those involved to remove the monument in Murray, noting Neal’s background as a Marine veteran in challenging a monument dedicated to Confederate veterans.

Neal faced a backlash for being a frontline advocate for removing the Murray monument. He left Murray in 2021 after he wasn’t brought back on his college football team as a volunteer coach.?

But he feels it’s still important to document movements, including ones that don’t achieve every tangible goal, for future posterity.

“A lot of times we look at the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech,” he said. “‘Oh, that’s great.’ Well, there’s a lot of bad that comes, too, and sacrifice that comes with all these things. And I think it’s important to capture the reality of some of that.”

]]>The Biden administration announced $714 million to help rural areas expand internet access. (Getty Images)

WASHINGTON — The Biden administration on Monday announced it will send $714 million to help rural areas in 19 states connect to the internet.

“The president honestly believes that in order to have the fullest opportunity available to bring manufacturing back, to bring precision agriculture, to reconnect young people to economic opportunity in rural places, the expansion of broadband access is essential,”

U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said on a call with reporters.

“And the announcement today is an additional step being taken by this administration to make that a reality in all parts of the country, regardless of how remote and rural they may be,” added Vilsack, a former governor of Iowa.

Congress approved the funding for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s ReConnect Program in the bipartisan infrastructure law that members of both political parties approved last year.

The Agriculture Department’s funding is a fraction of the $65 billion that U.S. lawmakers authorized for programs that aim to connect all Americans to the internet.

The additional funding is being distributed by the Federal Communications Commission and the Commerce Department, each of which have rural broadband and internet connectivity programs of their own.

This tranche of funding from the USDA, Vilsack said, would go towards 33 different projects.

The funding includes:

Alaska: A $35 million grant for Interior Telephone Company.

Alaska: A $35 million grant for Mukluk Telephone Company Inc.

Alaska: A $17.9 million grant for Copper Valley Telephone Cooperative Inc.

Alaska: A $12.6 million grant for Matanuska Telecom Association Inc.

Arkansas: A $30.4 million loan for Decatur Telephone Company Inc.

Arkansas and Missouri: A total of $13.4 million in grants and $13.4 million in loans for Ozark Telephone Company.

Arizona: A $3.5 million grant for South Central Utah Telephone Association Inc.

Arizona: A $25 million grant for Colorado River Indian Tribes.

California: A $25 million grant for Cal-Ore Telephone.

Georgia: A $9.5 million grant for Pembroke Telephone Company Inc.

Idaho and Oregon: A $15.4 million grant and a $15.4 million loan for Oregon Telephone Corporation.

Kansas: A $50 million loan for Craw-Kan Telephone Cooperative Inc.

Kentucky: A $9.4 million grant and a $9.4 million loan for Peoples Rural Telephone Cooperative Corporation Inc.

Kentucky: A $25 million grant for Duo County Telephone Cooperative.

Minnesota: A $7.9 million grant and a $7.9 million loan for Johnson Telephone Company.

Minnesota: A $6.8 million grant and a $6.8 million loan for MiEnergy Cooperative.

Minnesota: A $19 million grant for Meeker Cooperative Light & Power Association.

Missouri: A $29.5 million loan for Goodman Telephone Company Inc.

Missouri: A $14.2 million grant and a $14.2 million loan for Seneca Telephone Company.

Montana: A $12.1 million grant for InterBel Telephone Cooperative Inc.

Montana: A $35 million grant for Nemont Telephone Cooperative Inc.

New Mexico and Oklahoma: A $21.7 million grant and a $21.7 million loan for Panhandle Telephone Cooperative Inc.

Ohio: A $21.3 million loan for Amplex Electric Inc.

Oklahoma: A $5 million grant and a $5 million loan for Canadian Valley Telephone Company.

Oregon: A $30.6 million loan for Beaver Creek Cooperative Telephone Company.

Oregon: A $10.2 million grant and a $10.2 million loan for North-State Telephone Co.

South Carolina: A $6.2 million grant for Home Telephone Company Inc.

Tennessee: A $1.6 million grant for DeKalb Telephone Cooperative Inc.

Utah: A $2.2 million grant and a $2.2 million loan for Beehive Telephone Company Inc.

Washington: A $9.2 million grant and a $4.6 million loan for Public Utility District No.1 of Jefferson County, Washington.

Washington: An $18.1 million grant and an $18.1 million loan for Home Telephone Company Inc.

Washington: A $24.2 million grant for Public Utility District 1 of Lewis County.

Washington: A $3 million loan for Hat Island Telephone Company.

Land donated near Talcum in Knott County is slated to become the site of a new community. (Photo provided by the governor’s office)

The state has hired two engineering firms to plan and develop housing at two Eastern Kentucky sites for survivors from last summer’s devastating floods. Both are on former surface mines, and Gov. Andy Beshear indicated that others could be announced soon.

Beshear said last week that H.A. Spalding Engineers of Hazard will design infrastructure, including utilities, roads, bridges and sidewalks, at both sites. Bell Engineering, headquartered in Lexington, will design and manage development of homes, civic facilities and mixed-use residential buildings.

The two “high-ground communities” will be built on sites in Perry and Knott counties. The Knott County site is close to the Talcum community, near the Perry County line, and totals 75 acres. This property was donated by Shawn and Tammy Adams and could expand to nearly 300 acres. The Perry County site, 50 acres donated by the Ison family, is about five miles from downtown Hazard.

Beshear repeated that his administration is looking for more sites and said he hoped to have “a good update on that in the next week to two.”

Money from the Team Eastern Kentucky Fund will jump-start the project. The fund is also being used to partially finance small-project house construction with the help of local nonprofits. A Letcher County home was started in March, and four more are in the works.

Many victims are still in temporary housing; 114 households are still living in travel trailers, four are still living in hotels, and 14 are in state parks, according to the Commonwealth Sheltering Program.

The Spalding and Bell firms will coordinate with the state, Kentucky Housing Corp. and local nonprofits. Lisa Townes of H.A. Spalding said they look forward to the opportunity to be a part of building new communities for Eastern Kentuckians.

“All of us . . . know someone who lost their home and all their possessions, so this is very, very meaningful to us,” she said.

What kind of community?

Mark Arnold of Bell Engineering said his company is committed to building a residential community that “captures the spirit, heritage and history of Appalachia.”

“That’s where many of us were born, and where many of our families are from, and that’s what’s important to us,” Arnold said, adding that the firm doesn’t want to “build subdivisions where people live because they don’t have a choice (but) build places where people want to put down roots, build real community, and begin to really re-establish their lives.”

The state is “trying to build places where people want to relocate,” Public Protection Cabinet General Counsel Jacob Walbourn said at the East Kentucky Leadership Conference in Hazard on April 28. “Telling people in Eastern Kentucky they have to move is very dangerous, because it’ll create a lot of resentment.”

Eastern Kentucky is not about having all kinds of city things. It's about being able to go out in nature and explore and be outside, and you won't be able to do this on a strip job. I feel like they are trying to city-fy something that shouldn't be.

– Anna Eldridge, high school senior, Letcher County

Though officials say no one will be forced to move into the developments, Anna Eldridge, one of the young people invited to speak on a panel at the conference, opposes the plan though her family is still living in a trailer while they rebuild.

The high-school senior said she feels like it will cause more problems than it will fix, that there won’t be enough room for everyone in her Letcher County community to move, and she fears a loss of jobs in the community if people leave.

More than anything, she’s afraid such developments will take away from people the very things that she thinks makes living in Eastern Kentucky worthwhile.

“Eastern Kentucky is not about having all kinds of city things. It’s about being able to go out in nature and explore and be outside, and you won’t be able to do this on a strip job,” she said. “I feel like they are trying to city-fy something that shouldn’t be.”

Eldridge advocates rebuilding where individuals’ houses once were, in a creative way that incorporates approaches from other places where people have lived with and near flooding for generations.

However, state officials are focused on rebuilding homes out of floodplains, and this means moving to higher ground.

More money needed

Walbourn said at the conference that one of the biggest barriers is money. He said that for every dollar donated to the Team Western Kentucky Fund after that region’s 2021 tornadoes, only a quarter was donated to the Eastern Kentucky fund. There is about $13 million in the Eastern Kentucky fund, while the Western Kentucky fund has $52 million.

“I hope we as a state can come together to commit to Eastern Kentucky to do rebuilding0 right,” Walbourn said. “We need to stack and marshal resources.”

That’s why donations of land for housing projects are critical. They save the state money it would otherwise use to buy property and allows it to use those funds to hire engineering firms and others to manage development.

Arnold said he and his team are on the job as of Thursday’s announcement and are excited to get started. He was already thinking about new and different ways to design and build high-ground housing developments in Eastern Kentucky before the flood, so when Spalding reached out to bring in Bell as a partner, he leapt at the chance.

“We’re super excited and can’t wait to jump in,” Arnold said.

One of the first things Arnold said he wants to do is talk with flood survivors about what they want and need, so Bell can better understand their perspectives, and potentially implement those things in their designs. Arnold has worked with local partners in Mayfield for more than a year on plans for their downtown rebuild after a December 2021 tornado.

“When you come into a community that’s been devastated, it’s a different process,” he said. “You have to understand they’re dealing with trauma, and they may not be willing to talk yet” about plans for the future.

He said the projects in Perry and Knott counties are already well on their way, and that Team Kentucky and the myriad state agencies who have worked on them are handing the projects over with everything necessary in place and well-organized.

“We’re moving forward at a really good pace,” he said. “even though it doesn’t feel like it if you live there.”

This article was republished from The Rural Blog, a publication of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues based at the University of Kentucky.?

]]>Terry Thies adjusts the post of the bed that belonged to her mother. It’s the same bed she woke up in to find that her home had flooded overnight last July. (Photo by Xandr Brown.)

This story is a collaboration between The Daily Yonder and Grist. For more, watch the Daily Yonder’s video “How Broadband and Weather Forecasting Failed East Kentucky.”?

Terry Thies wasn’t worried about the rain that pounded on her roof last July.?

She had received no flood warnings before going to sleep that night. Besides, her part of rural Perry County in Eastern Kentucky often gets heavy rain.

So early the next morning when her foot hit the water lapping the bottom of her wooden bed frame, Thies’ first thought was that the toilet had overflowed. But as she scanned her bedroom for the water’s source, she realized this was something else entirely.?

“I came into the kitchen and opened the door and water was flowing down the lane,” Thies said. “Water was in my yard and rushing down. And I was like, well, I guess I’ve been flooded.”?

In the days leading up to the storm, the National Weather Service predicted heavy rain and a moderate risk of flooding across a wide swath of eastern Kentucky and West Virginia. What happened instead was a record-breaking four-day flood event in eastern Kentucky that killed a confirmed 43 people and destroyed thousands of homes.?

And though the National Weather Service issued repeated alerts, many people received no warning.

“Not a soul, not one emergency outlet texted me or alerted me via phone,” Thies said.?

“Nobody woke me up.”?

Thies’ experience in the July floods reveals troubling truths about Kentucky’s severe weather emergency alert systems. Imprecise weather forecasting and spotty emergency alerts due to limited cellular and internet access in rural Kentucky meant that Thies and many others were wholly unprepared for the historic flood.?

Efforts to improve these systems are underway, but state officials say expansions to broadband infrastructure will take at least four years to be completed in Kentucky’s most rural counties. In a state where flooding is common, these improvements could be the difference between life and death for rural Kentuckians.?

But there’s no guarantee they’ll come before the next climate change-fueled disaster.??

An urban bias in forecasting

The first system that failed eastern Kentuckians in July was the weather forecasting system, which did not accurately predict the severity of the storm. A built-in urban bias in weather forecasting is partially to blame.?

“Did we forecast (the storm) being that extreme? No, we didn’t,” said Pete Gogerian, a meteorologist at the National Weather Service station in Jackson, Kentucky, which serves the 13 eastern Kentucky counties affected by the July floods.?

For the days preceding the storm, the Jackson station warned of a ‘moderate risk’ of flooding across much of their service area. Observers with the benefit of hindsight might argue that a designation of ‘high risk’ would have been more appropriate. But Jane Marie Wix, a meteorologist at the Jackson station, wrote in an email to the Daily Yonder that the high-risk label is rarely issued, and simply didn’t match what the model was predicting for the July storms.?

“When we have an event of this magnitude, we’ll go back and look at, are there any indicators? Did we miss something? Was there really any model predicting this kind of event?” Gogerian said. “But when you looked at (the flooding in) eastern Kentucky, it just wasn’t there.”

“I don’t think anyone could have predicted just how bad it was going to end up being,” Wix wrote.??

Wix says the moderate risk warning was enough to warn people that the storm could have severe impacts in many locations. But the model’s inaccuracy demonstrates a flaw in the National Weather Service forecasting model system that was used at the time of the flood.?

Extreme weather is hard to predict in any setting, but rural regions like eastern Kentucky are at an additional disadvantage due to an urban bias baked into national weather forecasting systems, according to Vijay Tallapragada, the senior scientist at the National Weather Service’s Environmental Modeling Center.?

Forecasting models depend on observational data — information about past and present weather conditions —to predict what will come next. But there’s more data available for urban areas than for rural areas, according to Tallapragada.?

“Urban areas are observed more than rural areas … and that can have some, I would say, unintended influence on how the models perceive a situation,” he said.

Although spaceborn satellites and remote sensing systems provide a steady supply of rural data, other methods of observation, like aircraft and weather balloons, are usually concentrated in more densely populated areas.

“Historically, many weather observations were developed around aviation, so a lot of weather radars are located at major airports in highly populated cities,” said Jerry Brotzge, Kentucky state climatologist and director of the Kentucky Climate Center. “That leaves a lot of rural areas with less data.”?

Weather prediction models are based on past events, so the lack of historical weather data in rural areas poses a serious challenge for future predictions, according to Brotzge. “For large areas of Appalachia, we just don’t know the climatology there as well as, say, Louisville or some of the major cities,” he said.

This lack of current and historical weather observation can leave rural areas vulnerable to poor weather forecasting, which can have catastrophic results in the case of extreme weather events.?

Rural forecasting solutions?

A new forecasting model, however, could close the gap in rural severe weather prediction.?

The new Unified Forecast System is being developed by the National Weather Service and a group of academic and community partners. The modeling system is set to launch in 2024, but the results so far are promising, according to Tallapragada.

“In the next couple years, we will see a revolutionary change in how we are going to predict short-range weather and the extremes associated with it,” he said.

The problem with the current system, said Tallapragada, is that it depends on one model to do all the work.

A new application called the Rapid Refresh Forecast System is set to replace that single model with an ensemble of 10 models. Using multiple models allows meteorologists to introduce more statistical uncertainty into their calculations, which produces a broader, and more accurate, range of results, according to Tallapragada. He said that although the new system is not yet finished, it has already proven to be on par with, or better than, the current model.?

The Rapid Refresh Forecasting System will mitigate the disparity between urban and rural forecasting because it depends more on statistical probabilities and less on current and historical observational data, which is where the biggest gap in rural data currently lies, according to Tallapragada.

The system could also mean improved accuracy when it comes to predicting severe weather, like Kentucky’s July flood event.

“The range of solutions provided by the new system will capture the extremes much better, independent of whether you are observing better or poorly,” Tallapragada said. “That’s the future of all weather prediction.”

As extreme weather events become more common due to climate change, this advancement in weather forecasting has the potential to transform local and regional responses to severe weather. But without massive investments in broadband, life-saving severe weather alerts could remain out of reach for rural communities.

The crucial role of broadband

Over a year before the July 2022 floods devastated eastern Kentucky, some counties in the same region were hit by floods that, while not as deadly, still upended lives.

“There were no warnings for that flood,” said Tiffany Clair, an Owsley County resident, in a Daily Yonder interview. “It was fast.”

Clair received no warning when extreme rains hit her home in March of 2021, which severely damaged nearby towns like Booneville and Beattyville. “I did not think that those (towns) would recover,” Clair said.

Businesses and homes were impaired for months after the flood, affecting not only the people in those communities but those from neighboring communities as well.

“We live in a region where we travel from township to township for different things, and (the March 2021 floods) were a blow to the region and to the communities, because we’re kind of interlocked around here,” Clair said. “It’s part of being an eastern Kentuckian.”

A little over a year later, Clair faced more flooding, this time enough to displace her and her children. They now live with Clair’s mother.

This time around, Clair did receive an emergency warning, but questioned the method through which these warnings were sent. “(The warnings) did go all night, the last time, in July,” Clair said. “But if you don’t have a signal or if your phone’s dead, how are you getting those?”