Multiple Grammy winner Janis Ian, left, in 2008 plays with the late Jean Ritchie, a Kentuckian who grew up in Viper in Perry County and after moving to New York became a celebrated artist in the folk music revival. (Photo courtesy of Janis Ian)

It was big news last year when singer-songwriter and multiple Grammy winner Janis Ian announced Berea College would be the home for her archives.?

Berea College archivists have been working with the collection since the first materials arrived and are now ready to share some of what they’ve cataloged. The college is celebrating the archives’ opening with a series of events Oct. 17-20.

Ian’s archives span over a century, beginning with her grandparents’ immigration papers early in the 20th century through Ian’s career performing around the world and with musical legends including Joan Baez, Leonard Berstein, Dolly Parton and many others, to her advocacy for civil, women’s and LGBTQ rights.?

Click here for information about the “Breaking Silence” celebration and a short video in which project archivist Peter Morphew offers an introduction to the collection.?

Some highlights of the weekend’s events:

Friday and Saturday, Oct. 18-19: During the day guests can see samples from the Ian archives in the Hutchins Library atrium as well as archival footage from Ian’s public addresses and concerts.

7 p.m. Friday, Oct. 18: The play “Mama’s Boy,” written by Ian’s mother, Pearl, will be performed at the Jelkeyl Drama Center.

7 p.m. Saturday, Oct. 19: Janis Ian Tribute Concert at Phelps Stokes Chapel emceed by Silas House will feature Amythyst Kiah, Aoife Scott, Melissa Carper, S.G Goodman, Senora May.

]]>Former Gov. Matt Bevin, shown at a campaign rally for then U.S. President Donald Trump on Nov. 4, 2019 in Lexington, Kentucky. (Photo by Bryan Woolston/Getty Images)

The adopted son of former Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin is back in the United States — after he was removed earlier this year from an allegedly abusive Jamaican youth facility and left in care of that country’s child welfare system.

The boy, 17, is in a placement worked out with help of Jamaican children’s authorities after his adoptive parents, Matt and Glenna Bevin, did not immediately respond to inquiries about his situation, said advocates working behalf of him and seven other boys removed from the facility in February.

“He is safe,” said Rebecca Growne, a representative of a child advocacy foundation created by hotel heiress Paris Hilton, who has used her celebrity to shed light on conditions in so-called “troubled teen” facilities.

“He is in an appropriate placement.”

The Bevins, Growne said, are not involved in the matter.

Hilton’s foundation, 11:11 Media Impact, is a non-profit organization which advocates on behalf of children in allegedly abusive residential settings.

Hilton herself traveled to Jamaica in April to meet the boys and offer her organization’s support, a visit she mentioned in June testimony before Congress over her concerns about such residential programs.

Hilton said she, as a teenager, was placed involuntarily in several such facilities she said were highly abusive.

The Bevins did not respond to repeated queries about their son as officials and advocates sought to find a custodian for him, according to advocates with the Hilton foundation. As a result, he was placed in custody of the Jamaican child welfare system.

“They were not communicating with us,” said Chelsea Maldonado, also with the Paris Hilton foundation, who went to Jamaica to assist in the case. “Everyone has tried. No one has had success.”

Neither Matt Bevin, who served as Kentucky governor from 2015 through 2019, nor his lawyer responded to a request for comment.

Glenna Bevin, who is seeking a divorce from her husband, did not respond to a request for comment through her lawyer.

Matt Bevin, a conservative Christian, ran a campaign based in part on improving adoption services in Kentucky and reducing the number of children in foster care. In a 2017 interview on KET he called his desire to reform the system “the driving reason I made the decision to run.”

The Bevins are the parents of five biological children and four children they adopted from Ethiopia in 2012, including the youth who was sent to the Atlantis Leadership Academy in Jamaica last year.

Matt Bevin often cited the adoption in his political campaign and after he was elected in calling on members of Kentucky’s faith community to provide adoptive homes for children in need.

‘The perfect location for healing’

On its website, the Atlantis Leadership Academy describes itself as a “the perfect location for healing,” and an ideal place for youths who have cycled though other treatment programs without success.

But on Feb. 8, officials with the Jamaican Child Protection and Family Services Agency found otherwise when they conducted an unannounced welfare check on the eight teenage boys, ages 14-18, all U.S. citizens, according to a press release from the agency.

“During this visit, signs of abuse and neglect were observed, leading to the immediate removal of the teens from the facility for their safety,” it said.

The U.S. Embassy, in a statement, said it takes the welfare of U.S. children abroad “very seriously” and works closely with Jamaican child protection officials in such matters.

The Jamaican children’s agency did not elaborate on the abuse it observed at the academy but a lengthy story July 13 in the Sunday Times of London said the teens removed from the academy described beatings, violent treatment, isolation, lack of food, filthy, unsanitary conditions and cruel punishments such as being forced to lie face down on the floor for hours.

“I’d rather die than go back,” one boy said, according to the Sunday Times.

The case was also referred to criminal authorities which resulted in charges of assault and child cruelty against five former staffers.

‘He was just so dejected’

The removal of the teens from the academy set off a flurry of activity to identify the boys and find their families.

Dawn J. Post, a New York lawyer who specializes in family law and failed adoptions, was among lawyers who traveled to Jamaica to volunteer their help with the boys’ cases.

The U.S. embassy and child welfare officials were able to confirm the identity of the youths and begin searching for relatives who might take custody of those under 18, she said. Representatives of Hilton’s foundation joined the effort.

The 18-year-old, no longer in the family court’s jurisdiction, was returned to the United States in coordination with the U.S. Embassy and the youth’s family, the children’s agency press release said.

Custody arrangements were made for four more.

Ultimately, three boys ended up in the custody of Jamaica child welfare when no relatives stepped forward, Post said.

Post said she was able to meet and speak with the boys, who signed agreements to accept her voluntary legal services — including the Bevins’ son.

“This young man was the one I was most worried about,” she said. “He seemed the most dejected, with very little belief that anyone was coming for him or even knew he was missing. He was just so dejected and depressed after everything he had gone through.”

Post said she was able to make telephone contact with Glenna Bevin once, who said she needed to consult with her husband before discussing her son’s care. Post said Glenna Bevin cut off contact after that. The Bevins’ son returned to the U.S. in May.

One of the eight boys remains in Jamaica as officials and advocates try to work out arrangements for his return to the United States, Growne said.

The Atlantis Leadership Academy was closed in March by officials, according to a statement from the U.S. Embassy. It was not licensed as a school and had moved locations several times, finally to a small, two-bedroom cottage, the Sunday Times story said.

Most youths got classes online, intermittently, Maldonado said.

Families paid $8,000 to $10,000 a month in fees, she said.

‘Terrifying, clickbait headlines’

Atlantis Leadership Academy has not responded to requests for comment through its website and a toll-free line it lists is not accepting calls.

The Sunday Times story said its founder and director, an American named Randall Cook, did not appear at court hearings over the facility and is believed to have returned to the United States.

Meanwhile, the academy, though closed, appears to be pushing back on some of the allegations.

On its website, under the heading Media and FAQ, it accuses some outlets of “terrifying clickbait headlines” with “horrific, pre-determined narrative attacks.”

Its comments do not directly address the allegations but rather, question the media outlets that reported them.

“Do you feel as though what you receive from the media is a narrative or genuine, honest reporting?” it asks. “It is no surprise that as a direct result of lazy reporting, half-truths and craving for sensationalism above dignity and the public common good, most media houses have continued losing massive amounts of trust among their consumers.”

It also defends parents who place their children in facilities that purport to help difficult youths, saying they in most cases are well-meaning individuals, desperate for help.

“Parents are in a place of devastation,” the academy website said. “…There is virtually no compassion for a parent that is experiencing this situational trauma in their home and lives.”

Going forward, Growne said Hilton and the foundation remain focused on advocacy meant to bring awareness of the proliferation of such facilities, both in the United States and abroad. Their foundation currently is looking into conditions at another facility in Jamaica that houses more than 150 youths.

It also is looking for stronger federal and state laws regulating such facilities and more resources to help children in the community, rather than institutions.

Children’s residential facilities, including those promising help for troubled teens, have become a multibillion-dollar industry, often with little oversight, Growne said.

Marketing often is aimed at parents of adopted children and may paint a glowing picture of substandard facilities that some parents send children to sight unseen, Growne said. Some parents use “transport teams,” hired workers, to collect their children and take them to a facility, she said.

“I think it needs to be well-known that these facilities are out there,” she said. “The marketing does not live up to the reality.”

]]>

The Adair Youth Detention Center, site of a riot in late 2022, is one of the Kentucky facilities under investigation by the U.S. Justice Department. (Kentucky Justice and Public Safety Cabinet)

The mood was celebratory as Kentucky and federal officials crowded into the Capitol Rotunda on a cold January day in 2001 to announce the end of five years of federal oversight of the state’s problem-ridden juvenile justice system.

“We’re never going to slide back to where we were in 1995,” said then-Juvenile Justice Commissioner Ralph Kelly. “We know we’re on the road to victory.”

But slide back Kentucky has — despite sweeping reforms enacted under a 1995 federal consent decree that advocates say, by the early 2000s, made it a national model for rehabilitating young offenders.

Now, Kentucky faces the threat of renewed federal oversight after the U.S. Justice Department announced May 15 it is opening an investigation into whether conditions at eight juvenile detention centers and one residential center for offenders violate civil rights of youths.

In a letter to Gov. Andy Beshear, the department said it is investigating possible excessive use of chemical force (pepper spray) and physical force by staff, failure to protect youths from violence and sexual abuse, overuse of isolation and lack of mental health and educational services

And longtime observers of the system who have watched the downward slide — including Earl Dunlap, a juvenile justice expert appointed by the federal authorities? to monitor Kentucky’s compliance with the 1995 consent decree — say it didn’t have to happen.

“Disgusting and sad,” is how Dunlap described it. “You had people in leadership in Kentucky who should not have allowed this to happen. You went from nothing to something and then right back to nothing.”

Dunlap, who is semi-retired and lives in Illinois, said he became so concerned about reports of problems in juvenile justice that in March 2023, he wrote to Beshear warning him of the risk of failing to fully address problems.

While congratulating Beshear on efforts to reform juvenile justice, Dunlap added in his letter he feared such efforts might fall short of federal standards and result in future litigation.

Dunlap said he offered to provide the administration with assistance for reform efforts but did not get a reply.

Beasher’s office did not immediately respond to a request for comment about Dunlap’s letter.

But Terry Brooks, executive director of Kentucky Youth Advocates, said his organization has found the Beshear administration uninterested in outside input when it comes to juvenile justice, calling it a “closed shop.”

“Not only has there not been any outreach, there has not been a response to folks trying to reach out,” he said.

Problems build for years

Brooks said while problems have been building over the years in juvenile justice, Beshear, now in his second term, and lawmakers ultimately bear responsibility.

“This is clearly on the Beshear administration and the General Assembly,” he said. “Clearly the governor and the General Assembly abrogated their responsibility.”

Beshear defended his administration’s efforts to upgrade juvenile justice in a statement released Tuesday by Morgan Hall, spokeswoman for the Cabinet for Justice and Public Safety.

“In response to violent outbreaks and to enhance security for staff and youth, the Beshear-Coleman administration developed an aggressive plan starting in December 2022 to implement sweeping improvements to Kentucky’s juvenile justice system, for the first time since its creation nearly 25 years ago,” it said.

In December, Beshear announced the state would open a detention center for females only in Campbell County following the sexual assault of a female detainee in Adair County.

Beshear also has sought to address acute staffing shortages by increasing starting pay for youth workers to $39,127 a year and the General Assembly approved about $138 million a year each year in additional juvenile justice funds for fiscal years 2023 and 2024.

It also has worked to upgrade medical and mental health services, the statement said.

Efforts also are underway to reopen the Jefferson County Youth Detention Center, which Louisville Metro Council decided to stop funding in 2019 after operating it for nearly 40 years. That forced the state to take on housing juvenile detainees, some in distant counties at understaffed facilities, far away from families and requiring long drives back and forth for court appearances.

Dunlap calls that a huge blunder.

“The ramifications were that the largest volume of kids in the state had to be transported elsewhere,” he said. “It was just plain ridiculous.”

‘Take the initiative’

The legislature, under pressure from the 1995 consent decree, in 1996 created the Department of Juvenile Justice to oversee youths charged with and convicted of offenses, which previously had fallen under the Cabinet of Health and Family Services.

While the previous federal investigation focused on residential centers, where youths found guilty of offenses were sent for treatment, the state also elected to create a system of new regional detention centers to hold children with pending charges. Previously, in many counties, children were held in adult jails, generally in separate units.

Masten Childers II, health cabinet secretary for former Gov. Brereton Jones, said the state went beyond requirements of the consent decree.

Childers, who? oversaw negotiation of the 1995 consent decree with federal authorities, said he was “surprised and disappointed” to learn Kentucky once again is subject to a civil rights investigation of its juvenile facilities.

“If our consent decree had been followed, we would not be talking about this,” he said.

Still, he thinks the Beshear administration can use the investigation to improve the system should it result in federal enforcement.

“Kentucky needs to take the initiative,” he said. “This is not the time to be defensive.”

‘No win here’

Sen. Whitney Westerfield, R-Fruit Hill and longtime proponent of juvenile justice reform, said he’s concerned that the state’s system is becoming more like an adult prison model instead of one focused on rehabilitation and treatment of youths, many of whom have experienced significant trauma and have mental health issues.

The current Juvenile Justice Commissioner, Randy White, appointed by Beshear in March, is a 27-year veteran of the state adult prison system.

“The extent to which we make our system for kids more like a corrections facility and less a place for opportunities for kids, the more harm we’re going to do in the long run,” Westerfield said. “The more we approach it as a baby prison, the more damage we’re going to do.”?

Westerfield said he’s saddened that problems with Kentucky’s juvenile justice system have attracted attention of federal authorities but hopes it results in improvements.

“If this is what it takes, then that’s a good thing,” he said.

Meanwhile, he said, he’s concerned that the juvenile justice system is struggling even as Kentucky lawmakers enact tougher laws on juvenile offenders, citing misleading claims that today’s youths are more violent or that juvenile crime is increasing.

“Juvenile crime is not worse. It’s dropping,” he said. “Adult crime is dropping.”

Juvenile crime has been falling steadily and in 2020, was at its lowest level since 2005, according to a U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention report last year.

Still his fellow lawmakers rely on anecdotal events or a headline-grabbing crime as a reason to enact tougher laws, including one that takes effect July 1 to require mandatory, 48-hour detention for youths charged with serious crimes, Westerfield said. That has the potential to send an additional 400 youths a year into state juvenile detention facilities even as those facilities come under investigation by federal authorities.

“There’s no win here except the political victory for the sponsors and for the people who voted for it,” Westerfield said. “They’s going to get to say they’re tough on crime.”

‘Damn pepper spray’

The current federal investigation focuses on the eight detention centers and one residential center, the Adair Youth Development Center, the site of a November 2022 riot, resulting in a serious injury to staff and sexual assault of a female youth. In addition to those facilities the state operates five other youth development centers, eight group homes for juveniles and six nonresidential day-treatment programs.

In recent years, allegations of abuse, solitary confinement, overuse of force and overuse of adult corrections-type measures such as pepper spray have dominated headlines — initially in reporting by John Cheves of the Lexington Herald Leader — and more recently, outlined at legislative hearings including allegations of? sexual misconduct and disproportionate treatment of Black and multiracial youth.?

In January, state Auditor Allison Ball released a report requested by lawmakers detailing a series of serious problems with the system’s detention centers including overuse of force, significant understaffing, lack of clear policies of managing youth behavior and misuse of isolation.

The report, by the consulting firm CGL Management Group, also expressed concern about the Beshear administration’s introduction of pepper spray and tasers into juvenile centers, saying they are largely unnecessary.

“Current nationally recognized best practices do not support the widespread deployment of chemical agents or the use of electroshock devices (such as Tasers) within juvenile detention and instead recommend strategies to reduce or eliminate these uses of force,” it said.

The Justice Cabinet, in a statement, defended the use of pepper spray, also known as oleoresin capsicum, or OC spray.

“Pepper spray is a non-lethal, effective tool for both staff and juveniles, and is issued by adult and juvenile facilities across the country,” it said.

Further, it said, the legislature has mandated that pepper spray and tasers be issued to staff at juvenile justice facilities.

The outside audit warned use of pepper spray is especially risky for children with asthma or other health conditions or those on certain medications.

“As staffing levels improve, further consideration should be given to entirely removing pepper spray,” it said.

Dunlap, the former federal monitor, said he was shocked when Beshear authorized the use of pepper spray in juvenile detention centers last year, calling its use “old school.”

“The first thing I would do is get rid of that damn pepper spray,” he said. “They’re gonna kill someone with it.”

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Men of the legislature gathered with Senate President Robert Stivers to talk to media after overriding Gov. Andy Beshear's veto of a bill that preempted housing discrimination ordinances in Louisville and Lexington. (Kentucky Lantern photo by Liam Niemeyer)

FRANKFORT — The GOP-dominated Kentucky legislature overrode Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear’s veto of a bill targeting local source-of-income discrimination bans just a day after the governor had issued the veto.?

House Bill 18, sponsored by Rep. Ryan Dotson, R-Winchester, immediately became law Wednesday because of an emergency clause in the bill.?

In a gathering with reporters, Dotson said he believed ordinances passed by Louisville and Lexington, aimed at stopping discrimination by landlords based on a tenant’s source of income, were effectively dead.?

“There was nothing discriminatory about this measure,” Dotson said. “It was only to protect property rights, and no one should be forced to do business with the government.”

Beshear in a statement said discrimination should always be opposed, not enabled.?

“The override of my veto hurts Kentuckians by allowing direct discrimination against those with disabilities, as well as our senior citizens, low-income families and homeless veterans,” Beshear said.

Senate President Robert Stivers rejected the assertion that HB 18 would make it harder for veterans and low-income Kentuckians to access housing and took a swipe at zoning and tax policies in the state’s two largest cities.

“We, the General Assembly, sets policy, and we, the General Assembly, have the power of the purse,” Stivers said. “The reality is the city of Louisville and the city of Lexington have a homeless problem directly related to their bad policies.”?

Asked what policies in Louisville and Lexington he took issue with, Stivers pointed to zoning laws and property tax rates that “run developers out of the area.”?

Stivers touted the veto override as the first of several in this year’s legislative session,?

HB 18 would prevent local governments from adopting or enforcing ordinances requiring landlords to accept federal housing assistance vouchers from tenants for rent. Such assistance includes low-income housing assistance vouchers known as “Section 8” vouchers and vouchers?that help homeless veterans.?

Housing advocates have said local source-of-income discrimination bans do not force landlords to accept housing assistance vouchers, only that they can’t reject a prospective tenant solely on the use of vouchers to pay their rent. HB 18 preempts local source-of-income discrimination ban ordinances passed by Louisville in 2020 and another passed last month by Lexington.

Sen. Steve West, R-Paris, who sponsored a similar Senate bill whose elements were incorporated into HB 18, said he didn’t believe there was appetite among lawmakers to? “completely do away with zoning or venture too far into local business,” referencing a Republican-sponsored House bill that would revamp local zoning laws to promote housing development.?

West pointed to a bill by House Majority Floor Leader Steven Rudy, R-Paducah, that requires housing development plans to follow a set of “objective” standards so that property owners “know what they’re getting into” when setting out plans from community to community.?

Housing advocates have called on the legislature to invest $200 million in state-run housing trust funds to tackle Kentucky’s affordable housing crisis, especially after natural disasters in recent years have depleted housing availability in Eastern Kentucky and Western Kentucky.?

Stivers said there’s been discussion with those in the private sector to find housing solutions but mentioned that funding for housing was “about timing and sequencing” with what housing developers can actually produce. Stivers asserted there isn’t enough housing development capacity to use hundreds of millions of dollars in a quick time frame.?

Any housing funding the legislature approves would be “within the capacities of what individuals can actually produce during a biennial period,” Stivers said.?

Adreinne Bush, executive director of the Homeless and Housing Coalition of Kentucky, told the Lantern that developers have been able to use $20 million allocated by the legislature to the Rural Housing Trust Fund in 2023. She said she believed housing developers would be up to the task again.?

That $20 million housing funding was allocated in March 2023, and the first home groundbreaking, thanks to that funding, took place in November 2023.?

“That’s a really quick timeline,” Bush said. “We do have the capacity.”

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Sixty years ago, 10,000 people marched on the Capitol in Frankfort, demanding civil rights and equality under the law, March 5, 1964. (Public Information Collection, Archives and Records Management Division, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives)

I never got a chance to ask my grandmother about what March 5, 1964 was like for her. What she heard from speakers on the steps of the Kentucky Capitol. If she saw Martin Luther King Jr. or Jackie Robinson. What she felt standing with thousands of others from across Kentucky.

She didn’t speak much about that day when I was growing up and? visiting her Ohio home outside Cincinnati. I had never seen the photo until I found it online in 2021, and by that point Alzheimer’s disease had eroded her memories. Virginia Niemeyer died last year at 88.

But I do know she walked out the door of her Lakeside Park, Kentucky, home to board a chartered bus at 8 a.m., one of at least 300 people who traveled from Boone, Campbell and Kenton counties to hear King urge state leaders to pass a civil rights law. My grandmother Virginia was just one of 10,000 who gathered from across Kentucky that day for what became known as the Freedom March on Frankfort.?

I know she boarded that bus, paying a $3 round-trip fare, because the Cincinnati Enquirer published a picture of her the day after the march. She sat in an aisle seat, her gloved hand holding a protest sign. The story in my family was that my grandfather didn’t find out she had gone to Frankfort until she appeared in the paper the next day.

We often hear about the powerful words of the Rev. King, rightfully so. But there were plenty of Kentuckians who had been fighting for civil rights in their communities and organizing to make sure the March on Frankfort happened. Lacking? my grandmother’s account, I wanted a glimpse of that day through the eyes of others who were there and who made the day possible.?

Pictured on that bus with my grandmother, standing in the middle aisle, was the Rev. Edgar Mack, the executive secretary of? the Northern Kentucky branch of the NAACP and the pastor of St. Paul A.M.E. Church in Newport in 1964. Mack, who grew up in Shelbyville the son of a sharecropper, helped make sure Northern Kentucky was represented that day.?

“My dad was a true believer,” Rodney Mack, the son of Edgar, told me in a recent interview. “He believed in people, he believed in the movement, he believed that this was right, and he just wasn’t going to be quiet about it.”

Civil rights activists in Northern Kentucky had been working before the march to confront segregation and other racist laws and norms in Covington. Black women including Alice Shimfessel and Bertha Moore were integral to the protests and efforts desegregating public accommodations in Northern Kentucky even before a state civil rights law was passed, according to the Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky.

In the weeks leading up to the March on Frankfort, Rev. Edgar Mack was an ever-present name in newspapers as he spread the word to Northern Kentuckians about the march. According to newspaper articles, faith leaders met at a Covington YMCA a week before to discuss the march, with a rally organized at a local church “to generate enthusiasm” the weekend before.?

“The march shall be dignified, peaceful and prayerful,” Rev. Mack told the Kentucky Post and Times-Star in February 1964. “It will demonstrate our concern that the state Legislature pass the urgently needed civil rights bill for Kentucky.”?

The march achieved all of that, according to the accounts of people who were there, although it would be two years before a civil rights bill became state law. Sharyn Mitchell, who was a teenager from Berea when she joined the march, said she had “never seen so many Black people in my whole life.”

“Because from Capital Avenue, from the bridge, straight up to the Capitol, was wall-to-wall. I’m talking about up on the porches and then in the yards — wall-to-wall Black people,” Mitchell told historian Le Datta Denise Grimes, who was conducting an oral history project on the march that’s archived at the University of Kentucky.?

Freedom March on Frankfort gallery (Click on photos)

Freedom March, from left to right, Rev. Olof Anderson, Syod Executive of the Presbyterian Church, Louisville, 13-year-old Sherman McAlpin, Louisville, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Rev. Wyatt Walker, executive-secretary of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Dr. D.E. King, pastor of Zion Baptist Church, Louisville, and Frank Stanley Jr., chief editor of The Louisville Defender, March 5, 1964. ( Public Information Collection, Archives and Records Management Division, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives)

In the weeks after the march, 32 hunger strikers spent 104 hours in the Kentucky Capitol House chamber to try to convince legislators to pass the Civil Rights bill. March 16-20, 1964 (Public Information Collection, Archives and Records Management Division, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives)

Mitchell also remembered singing on the bus from Berea to Frankfort and at the state Capitol, a “groundswell of ‘We Shall Overcome.’”?

Sheila Burton, who was a high school student in Frankfort in 1964, remembered Rev. Edgar Mack as one of the civil rights leaders active in Frankfort in the 1960s. Mack had previously served as the president of the Frankfort NAACP before becoming a pastor in Newport.?

Burton had left her high school during lunch break to see the speakers, she told Grimes for the oral history project, inching her way up through the crowd.?

“I just remember being in the midst of the crowd and feeling like, you know, ‘I’m there. I was there.’ That I can say I was there,” Burton said in 2021. “I just wanted to say I was there.”

Jessica Knox, the daughter of Northern Kentucky civil rights leader Fermon Knox, who worked alongside Mack, remembered her father putting in weeks of organizing and work. He traveled to Lexington, Louisville and other parts of the state encouraging people to join the march.??

On March 5, white women came out of their homes on Main Street in Frankfort to offer marchers cups of water; another neighbor offered marchers the use of a bathroom, Knox told Grimes as a part of the oral history project,

“They were so sweet. And it was something we were not expecting at all,” Knox said. “[I]t made me realize that there are such beautiful people in this world.”

Inclusion of people — no matter who they were —? was central for Edgar Mack, according to his son Rodney. “He would find like-minded people — and he didn’t care where they came from,” Rodney Mack told me.?

While the large majority of the crowd were Black Kentuckians, according to newspaper accounts, allies also showed up in solidarity, including my grandmother. Virginia was a nurse at the former Booth Hospital in Covington, where Rodney Mack’s mother and Edgar Mack’s wife Lillie Mae Mack was also a nurse. It’s unclear if Lillie and Virginia had worked together at the time, as my grandmother left her job when she began to raise my father and aunt at home in the 1960s.?

While my grandparents, father and aunt moved to Ohio the same month as the march, in Kentucky the work of civil rights and racial equality continued. In 1966, Kentucky Gov. Edward Breathitt signed into law the first state civil rights legislation south of the Mason-Dixon line. Nonetheless, Rodney Mack said his father still had to file lawsuits to make sure he? and his siblings were afforded equal rights under that law.?

Rodney Mack said his father would refer to the March on Frankfort in church services as a “critical stepping stone” on the way to future challenges and progress. Rev. Edgar Mack moved on to be employed as a social worker traveling throughout Eastern Kentucky and eventually become a professor of social work at the University of Kentucky. He later moved to Nashville to take a position with the A.M.E. Church, and he died in Tennessee in 1991.?

“I don’t think he thought that it was ever over,” Rodney Mack told me. “There was always another ‘first’ that needed to happen to break ground for more than inclusion.”?

Rodney went to the March on Frankfort as an 8-year-old with his sisters, his mother driving a car because the chartered buses were full.?

When I asked him what his father would think of today’s political climate, he asked me to put myself in my grandmother’s shoes.

“Would you take your kids? Or go yourself on something like that these days? I don’t know that you would,” Rodney Mack said, saying that the fear of violence and other backlash is real.

“In some ways I’d like to be able to talk to my dad, tell him what’s going on,” Mack said. “I know, he’d just be shaking his head.”

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Senate Democratic Floor Leader Gerald Neal, left, introduces the panel for the final Black History Speaker Series event of 2024. The academics, from left to right, are Aaron Thompson, Anastasia Curwood, John Hardin, Kevin Cosby, and Ricky Jones. (Kentucky Lantern photo by McKenna Horsley)

FRANKFORT — Against the backdrop of the Kentucky General Assembly considering a couple of bills that would limit diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives in education, a panelist of Black scholars and academics met to define the state’s past and present with DEI.?

The discussion concluded the Kentucky Legislative Black Caucus’ annual Black History Speakers Series in Frankfort. The panel’s DEI focus comes in response to legislative efforts that many see as hostile to Black people.?

So far, the Senate has passed Senate Bill 6, which aims to limit DEI in public colleges and universities. House Bill 9, which includes barring universities and colleges from expending “any resources” to support DEI programs or DEI officers, has not yet received a committee hearing. Both are backed by Republicans, who control the majority in the General Assembly.?

Senate Democratic Floor Leader Gerald Neal, who is from Louisville and a member of the caucus, moderated the panel.?

Neal, who argued while voting against Senate Bill 6 in a committee earlier this session that such legislation would not advance Kentucky and would instead move the state backward, said at the start of the discussion that diversity in experiences, age, physical abilities, religion, race and more support stronger education environments, and, in turn, businesses.?

“Many say that these bills and these actions compromise academic freedom in our colleges and universities while representing a historical reaction that has manifested itself periodically,” Neal said.?

How did we get here??

In recent years, the acronym DEI has become the next political “boogeyman,” replacing CRT, or Critical Race Theory, and BLM, the Black Lives Matter movement, said Ricky Jones, a University of Louisville professor and chair of the Department of Pan-African Studies. The backlash to the acronyms are really about “the maintenance of white supremacy in Kentucky.”?

Jones said white supremacy is “a single group of people who believe because of the color of their skin, because they are white, they ultimately have the right to know, think and decide about everything of importance.” He spoke about the current state of diversity in Kentucky.?

“It’s an environment that is legislatively hostile and it is getting to the point where talented Black students and Black professionals will not come here, and talented Black students and professionals who are here will not stay, including your natives,” Jones said.?

Kentucky is not alone in considering such legislation and hasn’t been the first. Last year, Tennessee passed a law prohibiting “divisive concepts” in higher education. Florida also enacted legislation preventing universities and colleges from spending money on DEI initiatives.?

John Hardin, a 20th century African American historian and professor Emeritus of history at Western Kentucky University, contextualized the current discourse on DEI through Kentucky’s history. When it first gained statehood, many people who weren’t of European descent could not do a lot, he said. Over time, national events, such as the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education and the Civil Rights Movement influenced the state. In 1966, Gov. Ned Breathitt signed the Kentucky Civil Rights Act, making Kentucky the first Southern state to enact such legislation.?

“History is not dead people,” Hardin said. “History is change over time. What happened then has an impact on what’s happening now.”

Aaron Thompson, the first Black president of the Council on Postsecondary Education, said DEI efforts have closed gaps in higher education in Kentucky. CPE oversees Kentucky’s public higher education institutions, including eight universities. Thompson also previously answered questions about DEI in higher education during the committee hearing on Senate Bill 6.?

Thompson said the retention rate in two-year colleges for underrepresented minorities has increased about 13% and up about 8% for underrepresented minorities at four-year colleges.?

“The only population that we have been up over the last six years in, an increase, has been that of underrepresented populations,” he said.?

Kevin Cosby, the president of Simmons College, a historically Black college in Louisville, said studying history has value because “we get inspired by its accomplishments” and it has important lessons for the present. As the president of a historically Black college, Cosby said that “diversity is not on my agenda” as the institution has mostly Black students and diverse faculty.?

“What I want diverse and more equitable is in the allocation of resources,” he said.?

Where are we now??

Today, “diversity” can be seen as shorthand for “people who do not belong to the historically powerful group,” meaning the term is often coded Black, said Anastasia Curwood, department chair of history at the University of Kentucky.?

“It means difference within a certain body,” she said. “The difference does not have to be scary. … It simply means bringing in folks who have not historically had power, and these are Black people, Brown people, Native, Indigenous, disabled, LGBTQ, the list is long. But one thing everybody shares is a lack of access to full humanity.”

While debating Senate Bill 6 on the floor, bill sponsor Senate Republican Whip Mike Wilson, of Bowling Green, said his intention is to protect “diversity of thought” in higher education. He said he sees a trend of excluding conservatives from employment or promotion as scholars if they do not conform to “liberal ideologies.”?

The sponsor of House Bill 9, Rep. Jennifer Decker, R-Waddy, said in a previous statement that her legislation would direct public universities and colleges to give students “excellent academic instruction in an environment that fosters critical thinking through constructive dialogue.”?

While closing the discussion Thursday, Neal said Kentuckians are at a moment of opportunity “if we seize it.”?

“Those who negate what the past is fail to realize is that we cannot be informed to take advantage of the opportunities to be that future, make a better society, a life for us all,” he said.??

]]>KET will debut "Becoming bell hooks" on Feb. 27 and 29. (KET)

KET will celebrate the February premiere of its documentary “Becoming bell hooks” with preview screenings in Louisville and Lexington.

A KET release says the documentary “explores?the life and legacy of Kentucky-born author bell hooks, who wrote nearly 40 books and whose work at the intersection of race, class and gender serves as a lasting contribution to the feminist movement.

“The one-hour film examines bell’s childhood in Hopkinsville, her return to Kentucky in the early 2000s to join the faculty at Berea College, and how her connection to Kentucky’s ‘hillbilly culture’ informed her belief that feminism is for everybody,” says the release.

The film features selections from hook’s work read by Academy Award winner Octavia Spencer and includes interviews with friends and family, including feminist activist Gloria Steinem, Kentucky writers Crystal Wilkinson and Silas House, her younger sister Gwenda Motley and many others.

Steinem said bell was “one of the most universal writers and universal people” who made the feminist movement more accessible to all by going beyond issues of gender, race, class and geography. “It’s hard to imagine anyone who wouldn’t be enchanted, educated and made happier by her books.”

“Becoming bell hooks“?is a KET production, produced by Elon Justice and Sarah Moyer. It is funded in part by the KET Endowment for Kentucky Productions.

The documentary will air on KET at 9/8 p.m. Feb. 27 and Feb. 29.

Free preview screenings will be held at:

6:30 p.m. Feb. 20 at the Lyric Theatre & Cultural Center ?in Lexington.

7 p.m. Feb . 22 at the Speed Art Museum in Louisville.

To RSVP for a screening or find more information, visit KET.org/bellhooks.

This story has been updated. An earlier version contained errors in the dates of the preview screenings.

]]>An Israeli tank near the border with Gaza, Nov. 28, 2023. Photo by Amir Levy/Getty Images)

Lexington Mayor Linda Gorton on Tuesday released a joint statement with religious, civic and business leaders in Kentucky’s second-largest city appealing for peace in Gaza and Israel and respect for a diversity of views at home.

Gorton, Lexington Police Chief Lawrence Weathers and a group of Jewish, Muslim and Palestinian leaders in Lexington have been working on the statement since October, according to a release from Gorton’s office.

In addition to calling for peace in Gaza and Israel, the statement expresses “a united stance” to “keep Lexington peaceful, and all of its residents safe “at a time when there have been extremist attacks on Jewish, Muslim and Arab communities around the country.”

“Lexington is saying ‘not here’,” Gorton said.

Ten members of the Urban County Council have signed the statement. Business, faith, education, and civic leaders have also voiced their support, said the release.

Lexington residents are invited to sign he statement by sending their name and address to [email protected]. Residents are welcome to include the organization they represent.

The statement follows:

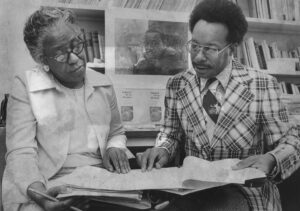

John Rosenberg

John Rosenberg, a Holocaust survivor who worked as a civil rights attorney in the U.S. Justice Department and built a nonprofit legal aid organization in Eastern Kentucky, will receive an honorary degree from the University of Kentucky at the December commencement.

Rosenberg will receive an honorary doctor of humane letters at the ceremony which begins at 3 p.m. Friday, Dec. 15,? at Rupp Arena.

Rosenberg helped found the Appalachian Research and Defense Fund (AppalReD) which is based in Prestonsburg, has five other offices across the region and provides civil legal representation to individuals and groups who cannot afford a lawyer.

A news release from UK says Rosenberg has served as a longtime civil and human rights activist and that “his activities since 1970 and his work in the state’s legal system have improved the lives of thousands of Kentuckians.”

The UK news release continues: “Rosenberg was born in Magdeburg, Germany, in 1931. On Nov. 9, 1938, 7-year-old Rosenberg and his parents were pulled from their home by Nazis and stood in the courtyard of the adjacent synagogue, where they were forced to watch the holy scriptures burned and the building interior blown up. For a year afterward, Rosenberg and his family stayed in an internment camp in Rotterdam, Holland, before coming to the U.S. in February 1940. The family lived in Spartanburg, S. C., for three years and then moved to Gastonia, N. C., where Rosenberg attended junior and senior high school. He was an Eagle Scout and president of his sophomore and senior classes.

“The first in his family to attend college, Rosenberg attended Duke University and worked in the dining halls all four years. While at Duke, he joined the Air Force Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) program and upon graduation served three years as a navigator and instructor navigator in the U.S. Air Force. After the Air Force, Rosenberg studied law at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and graduated at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, whereupon he went to work at the Civil Rights Division. He served there from 1962 to 1970 and made his mark as a litigator of racial discrimination cases, particularly in the South.

“While working for the Civil Rights Division, he met his wife, Jean, who has worked side by side with him for years. Together, they traveled to Eastern Kentucky, a trip that transformed their lives. Rosenberg was contemplating a move from the Department of Justice and learned of a fledgling organization that was slated to address the symptomatic issues of poverty and assist low-income persons with their legal needs in the region. That organization was the Appalachian Research and Defense Fund of Kentucky, also known as AppalReD Legal Aid.

“Rosenberg directed AppalReD and oversaw its expansion and efforts for more than 30 years, after its founding in 1970. He and his staff trained many UK law students, who worked as interns and clerks for the organization and then went on to become outstanding lawyers, academics and even judges in the intricacies of helping people deal legally with environmental and safety issues related to coal mining, consumer and housing matters, educational problems, public assistance, and family law matters, such as the termination of parental rights. Upon retiring from AppalReD in 2002, he founded the Appalachian Citizens Law Center in Whitesburg, Kentucky, to specifically address coal-related environmental, health and safety matters.

“Rosenberg remains highly active in his community. His adopted hometown of Prestonsburg has named a new town square — Rosenberg Square — for him and his wife, with a mural that showcases some of their history. Rosenberg has served on the Kentucky Public Advocacy Commission since 1994, including as vice-chair. He is a past member of the Board of Governors of the Kentucky Bar Association, where he has chaired the Donated Legal Services Committee, the Education Law Section and the Public Interest Law Section. He has served on the Pro Bono Committee of the American Bar Association and recruited lawyers to assist low-income persons on a pro bono basis. He has also served on the Board of Regents of Morehead State University, the visiting committee of the UK law school and the stakeholder advisory board for the UK Center for Appalachian Research in Environmental Sciences (UK-CARES). His activities since 1970 and his work in the state’s legal system have improved the lives of thousands of Kentuckians.”

For more information about UK’s December 2023 commencement ceremonies, visit https://commencement.uky.edu.

]]>

Rosalynn Carter’s legacy includes her support for Habitat for Humanity. She helped her husband Jimmy frame houses across the country for the charity. (Photo by Chris Graythen/Getty Images)

Former first lady Rosalynn Carter has died, according to the Carter Center, leaving a rich legacy of championing mental health and women’s rights.

She will be buried at the ranch house in Plains she and former President Jimmy Carter built in 1961. She died Sunday just days after the family announced she had entered hospice at the home.

She was married for 77 years to Jimmy Carter, who is now 99 years old and entered hospice early this year.

“Rosalynn was my equal partner in everything I ever accomplished,” Jimmy Carter said in a statement on the center’s website. “She gave me wise guidance and encouragement when I needed it. As long as Rosalynn was in the world, I always knew somebody loved and supported me.”

Tributes poured in from across the political spectrum Sunday, a testament to her broad popularity that transcended partisan politics and her enduring contributions to causes and charities that stoked her passion.

President Joe Biden and first lady Jill Biden on Sunday were at Naval Station Norfolk in Norfolk, Virginia, participating in a Friendsgiving dinner with service members and military families from the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower and the USS Gerald R. Ford.

“Time and time again, during the more than four decades of our friendship – through rigors of campaigns, through the darkness of deep and profound loss – we always felt the hope, warmth, and optimism of Rosalynn Carter,” the president said in a statement. “She will always be in our hearts. On behalf of a grateful nation, we send our love to President Carter, the entire Carter family, and the countless people across our nation and the world whose lives are better, fuller, and brighter because of the life and legacy of Rosalynn Carter.’’

Georgia Democratic Sen. Jon Ossoff said Georgia and the country are better places because of Carter’s contributions.

“A former First Lady of Georgia and the United States, Rosalynn’s lifetime of work and her dedication for public service changed the lives of many,’’ Ossoff said. “Among her many accomplishments, Rosalynn Carter will be remembered for her compassionate nature and her passion for women’s rights, human rights, and mental health reform.’’

Georgia Republican Gov. Brian Kemp paid tribute to her, recalling her service as Georgia’s first lady during Jimmy Carter’s term as governor starting in 1971.

“A proud native Georgian, she had an indelible impact on our state and nation as a First Lady to both,” Kemp said in a statement. “Working alongside her husband, she championed mental health services and promoted the state she loved across the globe. President Carter and his family are in our prayers as the world reflects on First Lady Carter’s storied life and the nation mourns her passing.’’

Former President Donald Trump said on X that he and his wife Melania joined in mourning Carter.

“She was a devoted First Lady, a great humanitarian, a champion for mental health, and a beloved wife to her husband for 77 years, President Carter,” said Trump.

Georgia GOP Congressman Rick Allen posted on the X social media platform: “Rosalynn was a beloved Georgian and dedicated her life to serving others. Our nation will miss her dearly, but her legacy will never be forgotten.”

Former U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi called Carter “a saintly and revered public servant” and a leader “deeply driven by her profound faith, compassion and kindness.”

Pelosi, a California Democrat, recalled how Carter, while her husband was serving as Georgia governor, was moved by the stories of Georgia families touched by mental illness and took up their cause, despite the stigma of the time.

“Later, First Lady Carter served as honorary chair of the President’s Commission on Mental Health: offering recommendations that became the foundation for decades of change, including in the landmark Mental Health Systems Act,” Pelosi said. “At the same time, First Lady Carter was a powerful champion of our nation’s tens of millions of family and professional caregivers.”

The eldest of four children, Rosalynn was born at home in Plains on Aug. 18, 1927. One of her best childhood friends was Ruth Carter, Jimmy’s younger sister. Jimmy Carter’s mother, Lillian, was a nurse who treated Rosalynn’s father when he was ill with leukemia.

Rosalynn enrolled at Georgia Southwestern College in 1945 after she graduated from Plains High School with honors.

Jimmy Carter was home on leave from the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis that fall when he asked her to go to a movie. By Christmas he’d proposed to her, but she turned him down because things were moving too fast for her. He soon asked again and the couple married at Plains Methodist Church July 7, 1946, a month after Jimmy graduated from Annapolis.

As Jimmy Carter climbed the Navy’s ranks, the couple started a family with sons John William arriving in 1947, James Earl III (“Chip”) in 1950, and Donnell Jeffrey in 1952. Daughter Amy was born in 1967.

Carter was accepted into an elite nuclear submarine program, and the young family then moved to Schenectady, N.Y. But when his father fell ill, Jimmy left his commission and moved back to Plains to take care of the family’s peanut business.

Rosalynn was an active campaigner during her husband’s political climb, beginning with his run for state senator in the early 1960s. By the time he was elected president in 1976, she vowed to step out of the traditional first lady role.

Five weeks after Inauguration Day, the President’s Commission on Mental Health was established with Rosalynn serving as honorary chairperson. The Mental Health Systems Act that called for more community centers and important changes in health insurance coverage, passed in 1980 at her urging.

In 1982, the couple founded the Carter Center in Atlanta, with a mission to “wage peace, fight disease and build hope.” She later founded the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving at the school now known as Georgia Southwestern State University, her alma mater. The institute was renamed the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers in 2020.

She was also an active partner in her husband’s philanthropic support for Habitat for Humanity, often joining him in framing houses for charity.

Three months after Jimmy entered hospice in February, the Carter family announced Rosalynn had dementia. She entered home hospice Nov. 17.

Rosalynn Carter is survived by her children — Jack, Chip, Jeff, and Amy — and 11 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren.

The Carter family requests that in lieu of flowers people consider a donation to the Carter Center’s Mental Health Program or the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers.

This story is republished from Georgia Recorder,?a sister publication of Kentucky Lantern and part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity.?

]]>The former surface coal mine in Roxana where U.S. Rep. Hal Rogers wants to build a federal prison. (Photo by No New Letcher Prison)

More than 185 organizations — from across Kentucky and the nation — are urging Congress to reject “fast-tracking” construction of a federal prison in Letcher County.

A Sept. 19 letter to leaders and members of congressional appropriations committees urges them to remove language that Rep. Hal Rogers of Kentucky put into a House appropriations bill in July. Opponents say Rogers’ provision, giving the long-debated prison a quick path to approval, would trample the rights of the public and prisoners.

Under Rogers provision, government decisions about “construction and operation” of the prison would not be subject to judicial review; there would be no environmental impact study, and the U.S. attorney general would be required to approve the prison within 30 days of the appropriations bill’s enactment.

Opponents in their letter say that Rogers’ provision blocking legal challenges — similar to Congress’ exemption for construction of the controversial Mountain Valley Pipeline in West Virginia — would strip away legal protections and recourse for inmates who already would be “isolated hundreds of miles from their loved ones” and “uniquely vulnerable to maltreatment and abuse.”

The letter also says, “Letcher County community members and other stakeholders from across the country should have a say when it comes to such a significant change in the community, particularly given the price tag of over $500 million taxpayer dollars and the false promises of prison-based economic development.”

Rogers has been been pursuing the project for years and appeared to prevail in 2018, but the Trump administration decided to defund the project, saying it was no longer needed, and the Biden administration excluded the project from its 2024 budget proposal. Rogers and other local boosters of the prison say it would create jobs and economic spinoffs in area suffering from the coal industry’s decline.

Rogers told Spectrum News in July: “The federal government needs more prison space. This property qualifies to the nth degree, and it’s proceeding. … We’ll continue to support it.”

The letter’s signatories range from the American Civil Liberties Union to Square Dance Farms of Blackey in Letcher County. It was sent to congressional members of the appropriations committees, the Problem Solvers Caucus and the Second Chance Task Force.

Read the letter:

2023-09-19 Stop 219 Organizational Sign-On Letter ]]>From left, Nancy Renville, Justine La Framboise, John Renville, Edward Upright and George Walker pose on the bandstand on the Carlisle school grounds in the late 1800s. Amos La Framboise is not pictured. The six children were members of the Spirit Lake and Lake Traverse bands of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate. (Photo by John Choate, courtesy of Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center)

Amos La Framboise and Edward Upright didn’t know that they’d never see their homes and families again.

The boys, of the Spirit Lake and Lake Traverse bands of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, set off to Pennsylvania in 1879 to attend the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

They didn’t know they would die at the school before they’d reach 15 years old; that their graves would be marked with military-issued headstones that were riddled with spelling errors; that there would be nothing to tell their story aside from the word “Sioux” on those headstones and the date of their death.

Their remains have stayed in Pennsylvania for more than 140 years. But they’re finally returning home.

Sisseton Wahpeton representatives traveled to Pennsylvania this week to oversee the disinterment of La Framboise and Upright after tribal chairs from the Spirit Lake and Sisseton Wahpeton tribes signed a pact with the U.S. Army. Tribal members plan to reinter the bodies on the Lake Traverse Reservation in northeast South Dakota this weekend.

The two boys were part of a group of six children from the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate to travel to the school together. They were the “best and brightest” of the time, said Tamara St. John, tribal historian for the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate and a member of the South Dakota House of Representatives. Many of the children were the sons and daughters of chiefs.

All four boys died before they reached adulthood. The two girls survived and returned home.

“We lost our next generation of leaders,” said St. John, who has spent years researching La Framboise and Upright in order to bring them home.

The children were among thousands of Native American youth across the United States sent to Carlisle to assimilate to white culture and to draw Native American chiefs into the nation’s capital.

Carlisle was the first government-run, off-reservation Native American boarding school in the United States. More than 500 boarding schools are known to have existed in the United States and Canada.

Assimilation tactics included cutting children’s hair, forcing them to speak English and renaming them with English names. Punishment for breaking rules was cruel and sometimes included beatings and sexual abuse.

“Kill the Indian in him, and save the man,” Richard Henry Pratt, superintendent of the Carlisle school, infamously said during an 1892 speech.

More than 180 children died between 1879 and 1918 and were buried at a cemetery near the school.

Since 2017, the remains of dozens of former Carlisle students have been repatriated to tribal nations. The Rosebud Sioux Tribe reburied the remains of nine children on its reservation in 2021.

The history of boarding schools in the United States and the repatriation of student remains is important for all Americans to understand, St. John said. Tribal history is currently a “subject of debate” in South Dakota, and the federal government’s assimilation tactics are little more than an asterisk in today’s history teachings, she said.

While the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate is welcoming two of its sons back home, St. John said several unmarked and unknown “Sioux” graves remain at the Pennsylvania cemetery.

“Children should be returned and allowed to be buried with their loved ones instead of far away in a field and forgotten about,” St. John said. “No child should have that. I think that’s part of Carlisle, you know, the idea that they were not important. But they are important to us.”

Fight takes years to bring boys home

St. John and the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate have been working to reinter the boys for years. It’s been a struggle over sovereignty with the U.S. Army, St. John said, since the boys were buried in an Army-run cemetery near the site of the former school.

The Army requires notarized statements by all close living relatives of the deceased saying they don’t object to the disinterment before the process begins. It took St. John several years to find La Framboise and Upright’s closest living relatives, who are elders from the Sisseton Wahpeton and Spirit Lake tribes.

“How do you find that next of kin to a child that died in 1879 with no children at the age of 13 or 14?” St. John said.

The process was burdensome for the elders, St. John said. And the Army’s policy asserted the reinterment was “just a family matter,” which disregards the importance of the reburial for the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate as a community, she added.

“It wound up being something of a false front, and I feel resentment for it because it became an obstacle and has been delayed for us for years,” St. John said, “but it’s also something that created division and questioning.”

The Army approved the disinterment requests in 2022 and scheduled the disinterments for summer 2023. After that, the agency stopped communicating with the tribe, St. John said. The lack of communication and growing frustration with the Army’s repatriation process led the Sisseton Wahpeton tribe to send a Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act request in March of this year. While the Army said the act doesn’t apply to Carlisle students, a federal notice was sent out in May scheduling the start of the disinterment process for September.

St. John said the effort to repatriate La Framboise and Upright will pave a path for repatriation for other tribes across the country.

“Our children are not soldiers. That is not their story,” St. John said. “They deserve to be remembered, to be with their families and to come home. … This really speaks to every child who was sent away and maybe lost. Now this is us saying we do care.”

‘They left together and they will come home together’

At least 233 students, nearly 3% of the 7,800 children who attended Carlisle, died while enrolled.

13-year-old Amos La Fromboise, son of tribal leader Joseph La Framboise, was the first to die. He died just three weeks after arriving at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1879 and was buried in the city’s cemetery. His cause of death is unknown, though a local newspaper said he was ill shortly before he died.

Edward Upright, son of Spirit Lake Chief Waanatan, died in 1881 after contracting measles and pneumonia.

The two other Sisseton Wahpeton boys, John Renville and George Walker, returned to Dakota Territory. Renville’s body was returned home by his father, Gabriel Renville, following the boy’s death in 1880 after contracting typhus. Walker was discharged from the school in 1883 because he was “extremely anxious.” St. John believes he likely died shortly after returning home.

The two girls sent to Carlisle, Nancy Renville and Justine La Framboise, returned home in 1880 and 1882, respectively. They survived into adulthood, though St. John does not know much about their lives.

This is the third time La Framboise’s remains have been disinterred and the second time for Upright. La Framboise’s grave was moved a month after his initial burial from the town’s “White persons’ cemetery” to the school’s newly established private cemetery. Both of the boys’ bodies were disinterred in 1927 after the Army took over the property. The more than 180 other children buried at the school were moved to clear space for a new building on the property.

St. John worried that there wouldn’t be anything in La Framboise’s grave before she drove to Pennsylvania with other tribal representatives. There have been instances when a grave was reopened and the child wasn’t inside or there were body parts from different children in the grave, St. John said.

The boys will be brought home “in the right way,” St. John said. The caskets will be covered with a buffalo robe, she said, which is “probably one of the most honorable, loving ways” to have wrapped individuals for burial at the time, she explained.

“They left together and they will come home together,” St. John said, “and they will be laid to rest together in a place we can protect them.”

This article is republished from?South Dakota Searchlight, part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. South Dakota Searchlight maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Seth Tupper for questions: [email protected]. Follow South Dakota Searchlight on Facebook and Twitter.

]]>Myriam Reynolds of Texas, the mother of a transgender son, said before he received care, he was unhappy and she has “no doubt that the health care my son accessed was life-saving.” (Screenshot from committee webcast)

WASHINGTON — U.S. House Republicans on a panel for limited federal government on Thursday argued that parents should not be allowed to let their transgender children have access to gender-affirming care.

“A parent has no right to sexually transition a young child,” the chair of the House Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution and Limited Government, Rep. Mike Johnson of Louisiana, said at a hearing on transgender youth. “Our American legal system recognizes the important public interest in protecting children from abuse and physical harm. No parent has a constitutional right to injure their children.”

Johnson, and several other Republicans, floated the idea that the federal government should get involved, but did not offer specifics on potential legislation. They argued that gender-affirming surgery should not be allowed for transgender minors. That type of surgery is rarely performed on patients under 18.

In Johnson’s home state, the Louisiana Legislature in early July voted to override a veto from Gov. John Bel Edwards, allowing a ban on gender-affirming health care for transgender youth to become law.

Thursday’s hearing reflects a broader trend. At least 21 Republican-led states have passed laws banning or restricting gender-affirming care for minors, according to the Movement Advancement Project, an organization that tracks LGBTQ+ state policies.

The wave of legislation has had a chilling effect on health care providers, who are wary of providing other care to transgender youth, such as mental health and other medical care.

Gender-affirming care can be social affirmations such as adopting a hairstyle or clothes that align with a transgender youth’s gender identity, or the use of puberty blockers and hormone therapy. Typically, in adulthood it can be gender-affirming surgery.

“When our Republican colleagues allege that gender-affirming care raises particular dangers or due process issues, that is fearmongering at its worst,” the top Democrat on the panel, Rep. Mary Gay Scanlon of Pennsylvania, said. “Picking on already vulnerable kids in order to stir up chaos that they hope to ride to success at the ballot box.”

Democrats said the hearing is a pattern of GOP lawmakers attacking transgender kids and their families.

Scanlon said that barring parents from making those decisions would be in violation of their parental rights. Republicans passed legislation for a federal “Parents Bill of Rights” in March pertaining to access to education-related materials.??

State laws

Several federal courts have either blocked or struck down state laws banning gender-affirming care for transgender youth, such as in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida and Indiana.

The top Democrat on the House Judiciary Committee, Rep. Jerry Nadler of New York, asked one of the Democratic witnesses, Shannon Minter, an attorney, what the federal courts have concluded about states moving to pass bans on gender-affirming care.

Minter, who is the legal director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights and is also transgender, said the federal courts have found that those state laws “severely burden parents’ fundamental rights to make medical decisions for their own children.”

“They’re blatantly discriminatory,” he said. “They violate the guarantee of equal protection because they do something that has just never been done before in this country, which is single out a particular group of people, transgender young people, in order to deny them medical care.”

Despite the federal court cases, Johnson argued that states have the right to regulate gender-affirming care, such as puberty blockers.

Puberty blockers were first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1993 to temporarily pause puberty in children who were going through it too early. When used in gender-affirming care for transgender youth, those adolescents can choose to start hormone therapy, in which they receive either estrogen or testosterone treatments, whichever one that aligns with their gender identity.

“We’re limited government conservatives, right,” Johnson said. “We obviously recognize that parents have a natural and fundamental right to the bringing up of their children to make decisions with regard to their care and custody and control. But at the same time, our legal system in this country, our law does not allow a parent to physically or mentally abuse or harm a child.”

May Mailman a senior legal fellow at the Independent Woman’s Law Center, a conservative advocacy organization, said states should be able to regulate who can have access to transgender health care.

“Unfortunately, I think you’re seeing this movement that states should not be able to regulate the practice of medicine and somehow federal judges should,” she said.

Life-saving care

One of the Democratic witnesses, Myriam Reynolds, is the mother of a transgender son. She said before he received care, he was unhappy and she has “no doubt that the health care my son accessed was life-saving.”

Reynolds said any health care provided to her son was through slow and careful decisions that were approved by her and her husband and that their son always had the opportunity to stop if he wanted to. He received puberty blockers as well as counseling.

“When my child came out, as transgender, there was not the hysteria that there is now about this,” she said. “To be looked at as a child abuser, or you know an indoctrinate or something like that, it feels very hateful and divisive.”

Texas Republican Rep. Wesley Hunt said that instead of parents jumping to gender-affirming care when a child tells them they have gender dysphoria, meaning their gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth, they should instead question “the root cause of that feeling.”

He compared that decision to his toddlers, whom if they could “have their way, they would have ice cream for breakfast, lunch and dinner and for every single meal in between. Oh, the wisdom of children.”

“In a sane country, we know that children aren’t mature enough to make adult decisions that will impact the rest of their lives, that’s why we have parents,” he said. “Children cry for ice cream, but as parents, we have the wisdom to know that ice cream is not in their best interests, particularly their long-term interest.”

He said that in 2024, Republicans will have an opportunity to “stop all this foolishness.”

Florida Republican Rep. Matt Gaetz, who is not a member of the panel, took aim at a recently passed law in Washington that protects transgender youth seeking gender-affirming care who are estranged from their parents.

“I am against transitioning children against the will of their parents,” he said.

Title IX

Several of the Republican witnesses criticized the Department of Education’s new rule that updates Title IX?to allow transgender youth who attend public schools to compete in sports that align with their gender identity.

One of the witnesses, Paula Scanlan, is a former NCAA athlete who swam at the University of Pennsylvania and shared a locker room with Lia Thomas, the first openly trans woman to compete in the NCAA women’s division. Scanlan said she opposed the Biden administration’s changes to Title IX and that transgender women should not be allowed to compete in sports that align with their gender identity.

The rule came as states with Republican state legislatures passed laws banning transgender students from competing in sports that align with their gender identity. House Republicans?recently passed legislation?mirroring the state legislation that bans transgender girls from competing in the sports that align with their gender identity.

Mailman, with the Independent Woman’s Law Center, said that gender ideology has destroyed “women and girls, by dissolving legal protections for women in athletics.”

Reynolds said as soon as her son came out as transgender, he stopped playing sports because of the rhetoric about transgender athletes competing in sports that align with their gender identity.

“That left a big hole in his life,” she said.

Theresa Lott signs the word for truth or honesty at the Kentucky Commission on the Deaf and Hard of Hearing in Frankfort. (Michael Swensen for Kentucky Lantern)

Sign language interpreters aren’t quite used to celebrity.

The job is usually more behind-the-scenes. Translating a diagnosis at the doctor’s office, standing off to the side of a stage.

But the COVID-19 pandemic thrust the late Virginia Moore — and her office, the Kentucky Commission on the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (KCDHH) — into the limelight. Moore and her colleagues signed the televised news conferences that Gov. Andy Beshear held and started a wave of conversation about accessibility and the dignity of communication and access to information.

With Moore’s death on Derby Day, her colleagues and friends continue that work without her.

Their office in Frankfort is laden with art by deaf creators — a globe made of nothing but hands, hands holding metaphorical ears, multi-colored hands spelling out Kentucky.

In early June, Moore’s empty office chair sat on a circular rug animated with hands signing the letters of the alphabet and the numbers 1-10. Her many awards adorn the walls.

In the window: monkeys stacked in a figurine frozen to say: Hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil.

The late Moore’s colleagues aren’t? interested in fame, said Theresa Lott, one of the American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters at the KCDHH and a regular interpreter for Beshear.

“We don’t want the attention on ourselves,” she said. “We want to facilitate language. That’s the goal.”

Lott and her colleagues serve as a surrogate for others’ communication. To do that, they said, one must have the heart of a servant. Their hands, facial expressions and body language are not their own. They embody the message they are translating. A viewer won’t usually get a sense of the interpreter’s personality.

“Our job is to let those people shine,” Lott explained. “And so it can be a little uncomfortable when we are put in that spotlight.”

At a Celebration of Life for Virginia Moore, Beshear said she left behind a “big legacy” and “big shoes to fill.”

And Kim Brannock, a public information officer for KCDHH, said Moore was the “ultimate advocate.”

Meet the women filing her shoes — all while serving the roughly 700,000 deaf and hard of hearing Kentuckians.

Rachel Morgan Kincaid?

Both of Rachel Morgan Kincaid’s parents were deaf, so ASL was her first language. As a child she went to speech therapy because, she said, she was “delayed.” Even now, she said, when she’s just talking with her friends or colleagues, she slips into sign.