Children watch as rescue personnel carry a manatee to the water during a mass release of rehabilitated manatees at Blue Spring State Park in Orange City, Fla., in February 2023. The fast-growing state of Florida saw a relatively small birth rate decline of 1% from 2022 to 2023, according to a Stateline analysis. (Phelan M. Ebenhack/Associated Press)

Births continued a historic slide in all but two states last year, making it clear that a brief post-pandemic uptick in the nation’s birth numbers was all about planned pregnancies that had been delayed temporarily by COVID-19.

Only Tennessee and North Dakota had small increases in births from 2022 to 2023, according to a Stateline analysis of provisional federal data on births.

Kentucky’s 51,830 births in 2023 represented a decline of 0.9% from the year before.

In California, births dropped by 5%, or nearly 20,000, for the year. And as is the case in most other states, there will be repercussions now and later for schools and the workforce, said Hans Johnson, a senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California who follows birth trends.

“These effects are already being felt in a lot of school districts in California. Which schools are going to close? That’s a contentious issue,” Johnson said.

In the short term, having fewer births means lower state costs for services such as subsidized day care and public schools at a time when aging baby boomers are straining resources. But eventually, the lack of people could affect workforces needed both to pay taxes and to fuel economic growth.

Nationally, births fell by 2% for the year, similar to drops before the pandemic, after rising slightly the previous two years and plummeting 4% in 2020.

“Mostly what these numbers show is [that] the long-term decline in births, aside from the COVID-19 downward spike and rebound, is continuing,” said Phillip Levine, a Wellesley College economics professor.

To keep population the same over the long term, the average woman needs to have 2.1 children over her lifetime — a metric that is considered the “replacement” rate for a population. Even in 2022 every state fell below that rate, according to final data for 2022 released in April. The rate ranged from a high of 2.0 in South Dakota to less than 1.4 in Oregon and Vermont.

Trends for Latina women

The declines in births weren’t as steep in some heavily Hispanic states where abortion was restricted in 2022, including Texas and the election battleground state of Arizona. Births were down only 1% in Arizona and Texas. When health clinics closed, many women might have been unable to get reliable birth control or, if they became pregnant, to get an abortion.

Hispanic births rose in states where abortion is most restricted, even as non-Hispanic births fell in the same states, according to the Stateline analysis. It’s hard, however, to tell how much of a role abortion access played compared with immigration and people moving to growing states such as Texas and Florida.

In states where abortion access is most protected, births fell for both Hispanic and non-Hispanic women.

“The big takeaway to me is the likely increase in poverty for all family members, including children, in families affected by lack of access [to abortion and birth control],” said Elizabeth Gregory, director of the Institute for Research on Women, Gender & Sexuality at the University of Houston.

Many of the nation’s most Hispanic states where abortion and birth control are more freely available saw the biggest decreases in births: about 5% in California, Maryland, Nevada and New Mexico.

“Hispanic women as a group are facing more challenges in accessing reproductive care, including both contraception and abortion,” Gregory said in a university report earlier this year. “Unplanned births often directly impact women’s workforce participation and negatively affect the income levels of their families.”

Hispanic women on average have more children than Black or white women. Their fertility rates rose throughout much of the 1980s and 1990s, then fell in the late 2000s to near the same level as other groups. That’s because both abortion and more reliable birth control became more widely available, Gregory said.

The fact that some of the steepest drops were in heavily Hispanic states outside of Arizona and Texas suggests that Latina women are continuing a path toward smaller and delayed families typical of other groups.

Kentucky’s population shifted older in a decade. Here’s how and why it matters.

Most of the decline in California has been associated with fewer babies born to Hispanic women, especially immigrants, said Johnson, of the Public Policy Institute of California.

“California has a high share of Latinos compared to other states, and so fertility declines in that group have a huge effect on the overall decline in California,” he said. California was above replacement fertility as recently as 2008, he added, and would still be there if Hispanic fertility had not dropped. California is about 40% Hispanic, about the same as Texas and second only to New Mexico at 50%.

Birth rates also declined steeply in heavily Hispanic Nevada and New Mexico, with each dropping about 4% from 2022 to 2023. But Arizona, Florida and Texas, also in the top 10 states for Hispanic population share but faster-growing, saw relatively small drops of about 1%.

Texas banned almost all abortions after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022. The state also requires parental consent for birth control, a rule that’s included federally funded family planning centers since a lower court ruling that same year.

Arizona also saw the number of abortions drop in 2022. After the high court’s Dobbs v. Jackson decision, an Arizona judge revived enforcement of a near-total ban on the procedure that was enacted in the Civil War era. Many clinics closed and never reopened.

Abortions in the state plummeted from more than 1,000 a month early in 2022 to 220 in July 2022, and never fully recovered, according to state records. The rate of abortions dropped 19% for the year. Births that year increased slightly, by 500, over 2021.

In Texas, Gregory’s research at the University of Houston research saw an effect on Hispanic births when an abortion ban took effect in 2021. Fertility rates rose 8% that year for Hispanic women 25 and older, according to the report.

Both Texas and Arizona also are growing quickly, making the smaller decreases in births harder to interpret, Arizona State Demographer Jim Chang noted. Chang declined comment on the effect of abortion accessibility on state birth rates.

Budget effects

Overall, the continuing fall in birth numbers could have significant effects on state budgets in the future. The slide augurs more enrollment declines for state-funded public schools already facing more dropouts since the pandemic.

“The decline we see in enrollment since COVID-19 is a bigger problem than just the decline in birth rates,” said Sofoklis Goulas, an economic studies fellow at the Brookings Institution. Rural schools and urban high schools have been particularly hard hit, according to a Brookings report Goulas authored this year.

“We don’t have a clear answer. We suspect a lot of people are doing home education or going to charter schools and private schools but we’re not sure,” Goulas told Stateline.

Still, states need to recognize declining births as an emerging factor in state budgets to avoid future budget shortfalls, said Jeff Chapman, a research director who monitors the trend at The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Nationally, births did increase slightly for women older than 40, indicating a continuing trend toward delayed parenthood, said William Frey, a demographer at Brookings.

“The last two post-pandemic years do not necessarily indicate longer-term trends,” Frey said. “Young adults are still getting used to a recovering economy, including childbearing.

This story is republished from Stateline, a sister publication of Kentucky Lantern and part of the nonprofit States Newsroom network.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Workers apply brick to the facing of new homes in a new subdivision in Frisco, Texas, Thursday, Aug. 12, 2021. (AP Photo/Tony Gutierrez)

Southern states continued to get the lion’s share of new residents this year as Texas, Florida, North Carolina, Georgia and South Carolina added almost 1.2 million people among them. The South was the only region that drew net new residents from other states.

Meanwhile, the national population grew by 1.6 million people from births and immigrants, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates released last week.

South Carolina had the largest percentage increase between mid-2022 and mid-2023, a 1.7% increase of about 91,000 residents, most of it from people moving in from other states. The Summerville area, inland from Charleston, has been a magnet for movers, drawing hundreds of new residents each month, according to a Stateline analysis of change-of-address data from the U.S. Postal Service.

South Carolina also rose into the top five in terms of the number of new residents, as Arizona tumbled from that spot to No. 7, with growth of about 66,000 people.

Despite booming populations in coastal areas, rural parts of South Carolina are still expected to decline 15%-30% over the next decade, the state predicts. Newcomers have helped offset an aging population that has seen more deaths than births, said Daniel Tompkins, a statistician at the state Revenue and Fiscal Affairs Office.

In Texas, the one-year increase of about 473,000 includes hundreds of thousands of people moving in from other states and countries as well as new births. The state is drawing a large number of movers to fast-growing suburbs, where newcomers tend to be younger than Texans in general and more likely to have a college degree, said State Demographer Lloyd Potter.

“Like so many others, work brought us here,” said Jason Hall, who recently moved to Georgetown, Texas, an Austin exurb north of Round Rock.

“There is much more opportunity here than where we were before, Las Vegas, and you don’t have the crazy housing prices of California,” said Hall, a surgical assistant whose wife works for an online retailer. He added that suburban Georgetown reminds him of the South Texas area where he lived after leaving the Army 20 years ago.

“Georgetown still has that Texas feel that Austin kind of lost,” Hall said.

Georgetown has had some of the largest numbers of people moving in, according to the postal data for the period covered by the census estimates — the year ending July 1.

With all the new people you need instant housing, but there’s going to be three cars in each of those driveways. It can take years for the infrastructure to catch up.

– Texas State Demographer Lloyd Potter

The destination list is dominated by Texas and Florida locales: in Texas, Georgetown as well as Katy and Conroe near Houston, and Aubrey and Prosper north of Dallas; in Florida, Port St. Lucie and Palm Bay on the East Coast and Wesley Chapel, north of Tampa.

Florida’s population boom, about 365,000 between mid-2022 and mid-2023, has been made up mostly of people 50 and older moving to the state looking toward downsizing and retirement, while Texas has drawn more working-age people.

In other states, Henderson, Nevada, and Queen Creek, Arizona, have drawn many new movers.

Growth in popular Texas suburbs has been so fast that roads and other infrastructure have been strained, said Potter, the state demographer.

“They’re building big apartment buildings and single-family houses, really just as fast as they can,” Potter said. “With all the new people you need instant housing, but there’s going to be three cars in each of those driveways. It can take years for the infrastructure to catch up.”

The newcomers are more likely to have college degrees than those already living in Texas, Potter said. The Lone Star State, like Florida, grew 1.6%.

In Florida, however, state officials have said growth will slow over the next decade as baby boomers age out of the 50-70 age range that feeds most moves to the state.

The state’s fastest-growing counties as of April, when the state makes its own population estimates, are in north and central Florida, where retirement communities are concentrated, said Richard Doty, a research demographer for the Bureau of Economic and Business Research at the University of Florida.

Population dropped in eight states, down from 19 last year: New York, California, Illinois, Louisiana, Pennsylvania, Oregon, Hawaii and West Virginia.

This story is republished from Stateline, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and donors as a 501c(3) public charity.?

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

States rely on federal funding for programs that can aid the disabled. Advocates say changes proposed by the U.S. Census Bureau could undercount the number of people with disabilities and decrease the funding each state receives. Here Prosthetist Erik Lindholm adjusts a prosthetic leg for 75-year-old Karl Sowa on Nov. 10, 2021 in Hines, Illinois. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty ImagSes)

The Census Bureau has proposed a major change to disability questions on its annual American Community Survey that advocates say will reduce the number of people who are counted as disabled by 40%, including millions of women and girls. The change in available data could affect federal funding allocations and the decisions government agencies make about accessible housing, public transit, and civil rights enforcement, they argue.

Catherine Nielsen, executive director of the Nevada Governor’s Council on Developmental Disabilities, said having correct data is vital not only because it helps identify gaps in the system but because it affects federal funding levels.

“Many providers are not reimbursed at 100% for the services they provide,” Nielsen said. “When we take into consideration this cut to the data, we’re essentially saying we have even less people that will qualify for support. If we have less people that qualify, that in turn tells the Feds they have less of a need to support these programs. The snowball effect of such a significant change will be greater than most can even anticipate at this time.”

Although some opponents of the change have said that the ACS disability questions needed revising because the survey currently undercounts the number of disabled people, they say they are worried that the new approach is worse.

Instead of the current yes or no answers to the six disability questions on the survey, respondents will be asked to provide a range of responses on how difficult it is for them to perform certain functions. The Census Bureau is recommending that only people who answer “a lot of difficulty” or “cannot do at all” be considered “disabled” by federal terms, advocates say.

“Part of the issue with what they proposed is they are asking this scale and then excluding every person who says they have some difficulty in terms of these functions. Even if you say you have some difficulty with all of these functions, you would not be included as disabled,” said Kate Gallagher Robbins, senior fellow at the National Partnership for Women & Families. “What does ‘some’ look like? Is that some of the time or some difficulty all of the time? For my own dad, who had a stroke and walks with a cane and a brace, is that difficulty for when he has those mobility aids or absent those mobility aids?”

The Census Bureau has stated that the revised questions will “capture information on functioning in a manner that reflects advances in the measurement of disability and is conceptually consistent with” the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health framework. The changes “reflect the continuum of functional abilities” and include a new question that includes psychosocial and cognitive disability and problems with speech, according to the notice for public comment.

Time for comment

When a federal agency proposes rules or changes to a standing process, it typically has a public comment period. The Census Bureau goes through a very long process where it tests the questions. Then it asks for public comment from stakeholders. The deadline for comments on the disability questions as well as other changes to the American Community Survey, which include asking about electric vehicles and changing the household roster questions, is Dec. 19.? Many organizations focused on civil rights issues, including disability advocacy groups, are weighing in.

The Consortium for Constituents with Disabilities, which includes 100 groups, commented that the new approach will likely miss identifying many people with chronic conditions and mental or psychiatric conditions.

The National Partnership for Women & Families, joined by more than 70 groups, including many state entities such as the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program, Disability Rights Iowa, and Nevada Governor’s Council on Developmental Disabilities, also has commented. They say that there was not enough consultation with the disabled community and that the changes are overly restrictive, which could affect disaster preparedness responses, emergency allocations for the Low Income Energy Assistance Program (LIEAP), enrollment efforts for Medicaid and funding for State Councils on Developmental Disabilities.

Who will be left out

The National Partnership for Women & Families released an analysis on Dec. 5 that estimated the new questions would leave out 9.6 million women and girls with disabilities. The organization notes that women are more likely to have disabilities related to autoimmune disorders, chronic pain and gastrointestinal disorders.

Robbins said she’s concerned about the effects this will have on people who apply for help paying utility bills or who rely on Medicaid.

“When people go to apply for those [LIEAP] funds, what is going to happen? Are there not going to be enough funds left? Will they do another application?” she said.

States are also going through the process of unwinding a pandemic-related Medicaid policy, which allowed people to stay enrolled in Medicaid without going through a renewal process. People who are no longer eligible for Medicaid or couldn’t finish the renewal process are being disenrolled. Robbins said data excluding many people with disabilities could affect efforts to re-enroll people.

“People are losing their Medicaid and we’re in a situation where we don’t know how to figure out who needs Medicaid and [Children’s Health Insurance Program] and direct our efforts to make sure people don’t lose health insurance,” she said.

Eric Buehlman, deputy executive director for public policy at the National Disability Rights Network, has a disability that includes not having vision from the left side of his face and attention issues, according to the organization’s website. He said the new questions could affect him and other people with disabilities who use public transportation if the data doesn’t show a need for more paratransit programs.

“I’m not supposed to drive, so I use public transportation to go everywhere. But under these [current] questions, I would have checked yes, for a person with a disability as they currently are. But under the way these [new questions] are, I’m not sure I would consider myself to be incapable of doing any of the six questions listed,” he said.

Buehlman said this could hit areas of the country that are more impoverished, which likely have a higher level of people with disabilities, harder than others. The connection between poverty and disabilities have been well documented, including by the Census Bureau. Its Supplemental Poverty Measure shows that in 2019, 21.6% of disabled people were considered poor, compared with just over 10% of people without disabilities. And in 2021, the American Community Survey found that the South had the highest disability rate. Of the five states with the highest poverty rates that year, four were in the South — Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi and West Virginia. The fifth was New Mexico.

“All of a sudden this connection between poverty and disability which does exist out there, doesn’t appear like it is (under the new survey). And these are areas of the country that may not have as many resources … It could have a higher negative impact in areas that are already underfunded,” Buehlman said.

Timing of changes particularly bad

The change in the survey questions could also have an impact on civil rights enforcement, said Marissa Ditkowsky, disability economic justice counsel at the National Partnership for Women & Families. Disparate impact claims, which focus on the effect a policy has on a protected class, including people with disabilities, could be affected by a change in data, she said.

“They are literally using math in these disparate impact claims to make these claims,” she said. “When you don’t have the ability to do that, I can’t imagine the [Equal Employment Opportunity Commission], [the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services], all of these agencies that enforce civil rights laws, I can’t imagine it will make their lives any easier.”

Opponents of these changes add that the timing of this new approach is particularly harmful when so many Americans are experiencing disabilities as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Long COVID symptoms can include shortness of breath, fatigue, and difficulty thinking and concentrating. In 2021, the Biden administration released guidance on how Long COVID can be a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Ditkowsky, who herself has Long COVID, said it seems counterintuitive to narrow the definitions for people with disabilities at this time.

“We’ve had one of the biggest mass disabling events in a long time with COVID-19 pandemic,” she said. ” … But the questions don’t necessarily get at a lot of the issues that Long COVID patients or patients with chronic conditions and people with chronic pain experience.”

To comment on the changes to the American Community Survey go to regulations.gov and click on comment.?Deadline to comment is Dec. 19, 2023.

]]>Ukrainian immigrant Dmytro Haiman, pictured in Dickinson, N.D., is one of the international workers the state has recruited to work in its booming oil industry. North Dakota’s shale oil boom contributed to a nation-leading 11% boost in personal income over the past four years. (Jack Dura/The Associated Press)

Residents of some Midwestern and Mountain states gained the most income per capita during the past four years, a Stateline analysis shows, as competition for workers drove up wages in relatively affordable places to live.

With the COVID-19 pandemic now in the nation’s rearview mirror, Stateline’s analysis offers a more complete understanding of how some states’ residents benefitted economically — and others didn’t — as policy decisions and Americans’ choices shuffled state-by-state outcomes.

The oil and gas industry boosted the per capita incomes for residents of North and South Dakota. Mountain states such as Utah saw high earners moving in from California, Oregon and Texas.

Kentucky’s per capita income increased 4.6% from 2019 to 2023 to $54,321, but Kentucky is still a poor state, ranking 47th among the 50 states and District of Columbia.

States where inflation-adjusted income declined included Alaska, where oil drilling has been in long-term decline, as well as Georgia and Maryland.

In Kentucky, per capita income has increased 4.6% since 2019 to $54,321 — 47th lowest among the states and District of Columbia.

Inflation took the biggest bite out of paychecks in the West and South, with consumer prices rising about 20% in those regions between mid-2019 and mid-2023, according to U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis figures compiled for Stateline by the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center in Washington, D.C. Inflation was a little lower in the Midwest, about 19%, and about 16% in the Northeast.

Stateline’s analysis calculated gains in per capita personal incomes after regional inflation between the second quarter of 2019, before the pandemic, and the second quarter of 2023, the latest available from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Per capita personal income, which includes all kinds of income from wages to business income and pandemic support payments, often is used as a barometer of economic health for states.

Many of the states in the Mountain West, Midwest and New England that experienced large income increases have scenic or affordable areas that have attracted remote workers looking for a lower cost of living and proximity to recreation.

“Things changed fast. Now there’s competition for workers and upward pressure on wages, and people from Oregon and California are saying ’Hey I could live next to five national parks. This is an incredible place,’” said Shawn Teigen, president of the Utah Foundation, a nonprofit that monitors Mountain State trends.

Newcomers to Utah, for example, brought both more income and oftentimes smaller families than the longtime Mormon population, boosting per capita incomes, he noted. And competition for scarce service and manufacturing workers has forced employers to pay more.

“This used to be a place where we could bring businesses in and say, ‘You can pay minimum wage and people will take the jobs because it’s not expensive to live here,’” he said.

Inflation-adjusted per capita incomes in Utah have grown by about 8% since 2019. Incomes in Colorado, Maine, Montana and Nebraska also grew by roughly that much. Incomes in Arizona, Idaho and Missouri increased by about 7%.

But the greatest gains were in North Dakota and South Dakota, where inflation-adjusted incomes increased by 11% and 9%, respectively.

North Dakota’s per capita personal income rose to $73,414, giving it the 12th highest income in the country, up from 16th in 2019. The gains allowed it to leapfrog states including Illinois, Minnesota and Virginia.

Growth in North Dakota’s energy industry continues to roar ahead, with taxable sales and purchases by the industry up more than 50% in recent quarters compared with the previous year, according to state estimates through mid-2023.

Unemployment has remained below 3% — and in recent years it has stayed low even in winter months, when outdoor work used to stop in brutally cold weather, said Kevin Iverson, a demographer at the North Dakota State Data Center.

The major impediment now is finding more workers to hire, Iverson said.

“It is no longer surprising to see businesses spend their advertising dollars on recruiting workers instead of customers,” Iverson said. The state recently created an Office of Legal Immigration to help recruit workers from abroad and among work-authorized immigrants already in the United States.

Incomes didn’t grow as much in most of the Northeast, partly because low-wage service workers have fared better than the high earners who predominate in the region, said Lucy Dadayan, principal research associate at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. Some of the highest-income areas in the country, including Connecticut and the District of Columbia, were in the bottom 10 for income growth. New Jersey and New York weren’t far ahead.

Those states still have among the highest incomes, though. Connecticut fell to No. 3 for personal income per capita overall at $86,674, from No. 2 in 2019, behind Massachusetts at $88,197 and the District of Columbia at $100,971.

“Connecticut, New York and New Jersey have a higher share of high-income taxpayers, and the salaries of low-income workers increased far more in the pandemic,” Dadayan wrote in an email. “Moreover, some of the income for high-income workers is often dependent on the stock market performance, which declined in 2022.”

The knocks to personal incomes affected state revenues. In Connecticut, personal income tax revenue took a $1.3 billion hit in fiscal 2023, down nearly a third in one year and erasing gains since fiscal 2019, according to state comptroller records. Comptroller Sean Scanlon blamed the drop on 2022 stock market losses in his annual report to the governor.

However, Connecticut’s general fund revenues showed a surplus overall in fiscal 2023 because of strong gains in use and sales taxes as hospitality and tourism industries recovered. Democratic Gov. Ned Lamont signed a tax cut bill in June.

Both Alaska and North Dakota have economies driven by oil, but North Dakota’s shale boom is still on an upswing while Alaska’s production has been in decline since the 1980s, helping North Dakota rise to the top of income growth statistics while Alaska sunk to the bottom. Alaska’s per capita income dropped 2.4% after inflation over the past four years.

North Dakota landowners are seeing continued profits from oil leases on private land. Alaska’s oil, however, is largely on public land that has seen more cutbacks in drilling rights, said John Connaughton, professor of financial economics at the Belk College of Business at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

State-by-state income rises across the Midwest were “all over the map,” from North Dakota’s double-digit percentage increase to just 2% for Wisconsin and 3% for Kansas and Michigan, said Nina Mast, who studied the region’s wage trends in the pandemic in an October study for the Economic Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington, D.C.

The region as a whole suffered lower wage growth compared with other regions in the pandemic through 2022, threatening to increase inequality and hurt middle-class workers, who increasingly lack union representation, Mast said.

Michigan became the first state to repeal an anti-union “right to work” law in March, a step that could help empower workers there, Mast said. “It was a really historic step that could really have important effects for workers in the Midwest.”

This story is republished from Stateline, a sister publication to the Kentucky Lantern and part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: [email protected]. Follow Stateline on Facebook and Twitter.

]]>The aging of Kentucky's population will place new demands on the health care system. The National Council on Aging reports that about 95% of older adults have at least one chronic condition, such as diabetes and heart disease, and that almost 80% have two or more chronic conditions. (Getty Images)

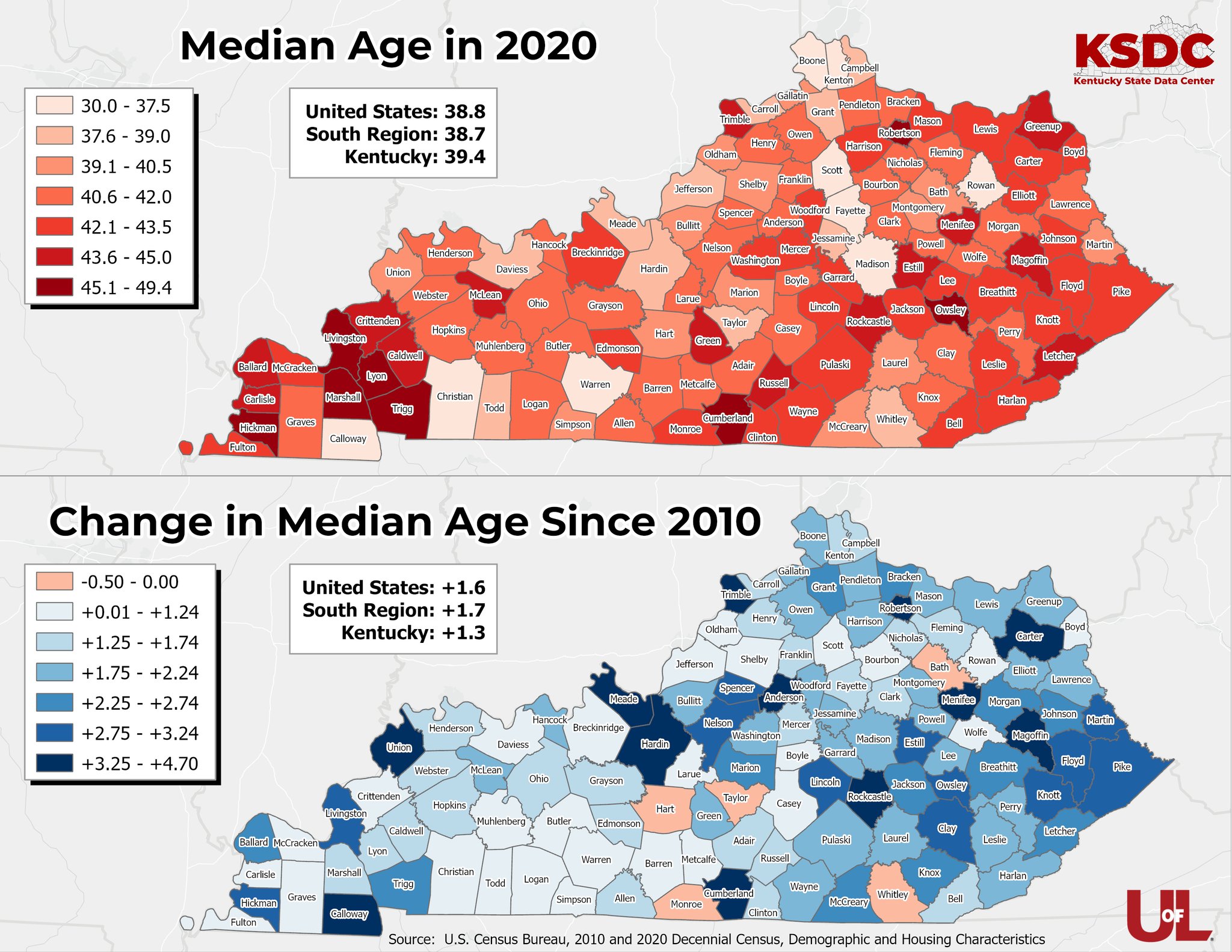

Kentucky’s population is shifting older, new data shows, with the oldest counties in the western part of the state.?

Counties with colleges and military clusters are home to the younger populations, according to analyses of new Census data by the Kentucky State Data Center (KSDC).

Eastern Kentucky is aging faster than the rest of the state, according to KSDC, which could be because of young people moving away.?

Between 2010 and 2020, the median Kentuckian age increased from 38.1 to 39.4. The population ages 65 and older also increased from 13.3% to 17%.?

An aging population — and fewer babies

“It’s not unexpected that the population is aging like this,” said Matthew H. Ruther, the KSDC director and a University of Louisville professor.?

However, the increase from 13% to 17% is “a really big jump,” he said. “And it’s not done yet. We’re going to still be seeing this going into the future.”?

In fact, Ruther estimates the 65 and older population will hit 20%.??

“The peak of the baby boom was in 1957,” he explained. “Those people are now 66. And so you’re … still going to be seeing this older population get larger, both in absolute terms and as a percent of the population.”?

With that increase, the state will need to consider the medical needs of the older population and the demands that will be placed on the health care system. The National Library of Medicine in 2008 reported that chronic conditions are more prevalent in older communities, producing greater utilization of health care services.?

The National Council on Aging said in March that about 95% of older adults have at least one chronic condition, such as diabetes and heart disease. Almost 80% have two or more chronic conditions, according to the Center on Aging.?

Yet large areas of Kentucky suffer from a lack of primary care providers.? The Kentucky Primary Care Association said in 2022 that 94% of the state’s 120 counties don’t have enough primary care providers.?

“People are already having trouble getting to doctors or hospitals because of supply issues,” Ruther said. “If nothing changed, then this is going to become more problematic in the future.”?

And while the older age group widens, some younger groups are smaller. That means fewer people are preparing to enter the workforce than are getting ready to leave it.?

We see fewer young people, in part, because people are delaying starting a family, Ruther said.?

Deaths exceeded births in 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, when there were nearly 4,000 more deaths than births in Kentucky. In 2021, deaths exceeded births by 8,089, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The trend is continuing. Preliminary data shows that in 2022 Kentucky deaths (57,269) exceeded births (52,458) by about 4,800.

The CDC said that in 2021, the mean age of American mothers at the time of their first birth was 27.3 years. That’s up from 27.1 in 2020.?

“People wait longer to have children,” Ruther said. “And then when people wait, they tend not to achieve their intended fertility.”?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says that “peak reproductive years” are between the late teens and late 20s.?

“By age 30, fertility (the ability to get pregnant) starts to decline,” ACOG says. “This decline happens faster once you reach your mid-30s. By 45, fertility has declined so much that getting pregnant naturally is unlikely.”?

These birth declines are “also not unexpected,” Ruther said. “But there are definitely going to be some ramifications for school systems across the state,” such as lower enrollments.?

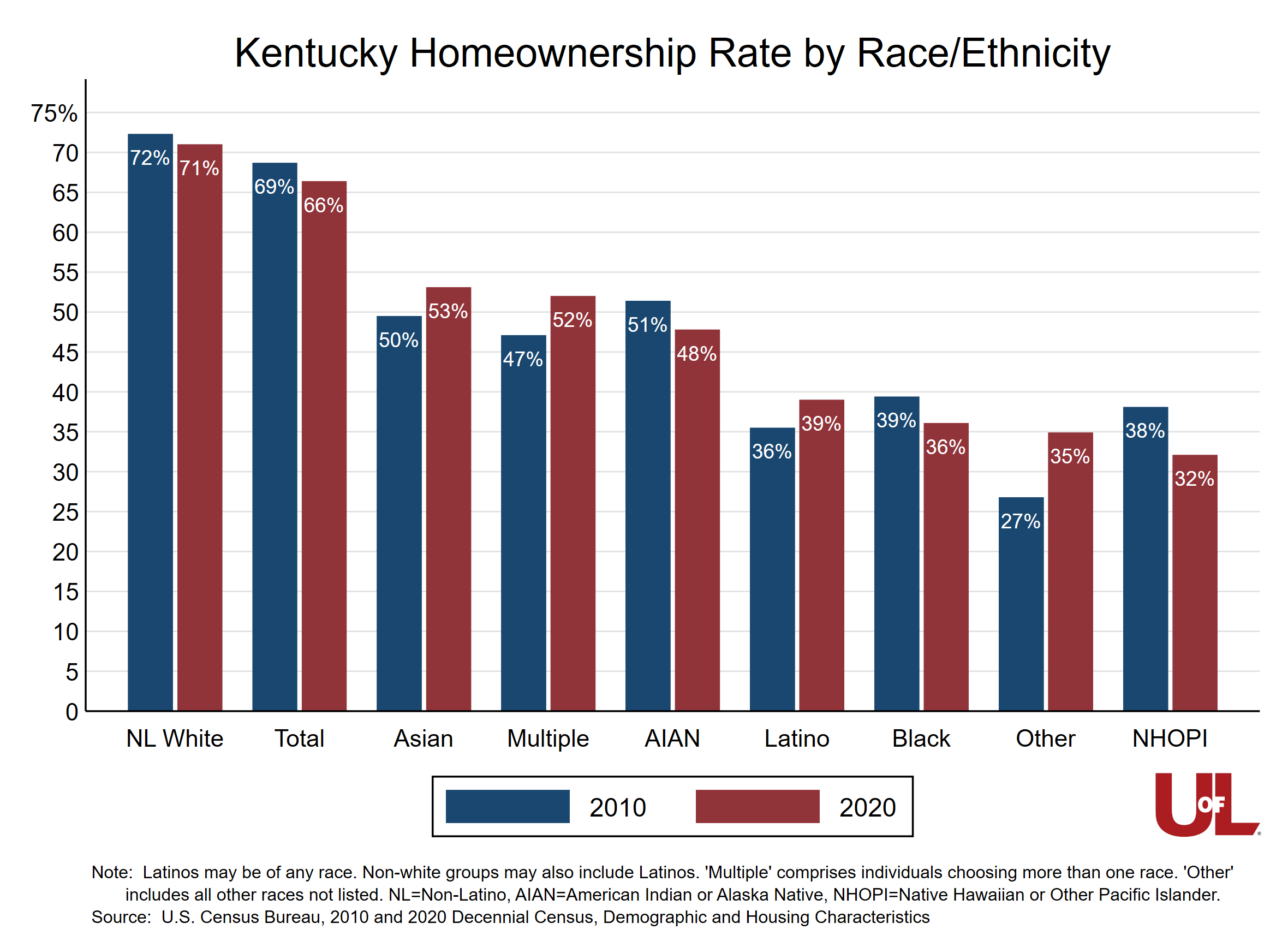

Homeownership disparities — by race

Meanwhile, the percent of Kentuckians who own homes declined from 2010 to 2029.

Between 2010 and 2020, homeownership in Kentucky declined overall from 69% to 66%. Factors may include the price of buying a house rising faster than wages and not enough access to credit, according to the KSDC.?

Beyond the general decline, there exist disparities between white and Black homeowners, Ruther said.?

Homeownership for white Kentuckians dropped from 72% to 71% over the decade, while for Black Kentuckians it fell from 39% to 36%.?

“Homeownership isn’t the end-all be-all of life, right?” Ruther said. “Some people don’t want to own a home. There’s … nothing necessarily wrong with that. But it is the primary way that people — that households — build wealth.”?

“Wealth-building opportunities are limited when you are renting,” he added. “So that’s … going to reverberate into the future.”?

A change in single households?

Kentucky is also seeing an increase in single-person households.?

“When we think of single-person households, most people tend to think of young people living carefree on their own,” Ruther said. “But a lot of the single-person households are actually … older individuals who are widowed or never married.”?

Especially in the western and eastern parts of the state, single-person households tend to be older people, Ruther said. Single-person households in urban areas like Lexington or Louisville are younger people, often college students living in apartments.?

“It’s sort of new that people are living by themselves,” Ruther said. “I don’t think that the number of single-person households outnumbers the number of two-parent family households, but it’s probably very close at this point.”?

COVID-19, floods and tornadoes

This data only covers up to 2020, so much isn’t represented, such as the full effect of COVID-19, as well as the housing and migration issues brought on by the deadly tornadoes in West Kentucky and the back-to-back floods in the East.?

The demographic fallout over these events, Ruther said, should show up in the next few data releases.?

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Parents walk with their 7-year-old and 10-week-old sons in June of 2020 in Stamford, Conn. Births increased last year by 262 in Kentucky but most states saw fewer babies in 2022. (John Moore/Getty Images)

Fast-growing Texas and Florida had the biggest increases in the number of births last year, while a dozen other states — half of them in the South, including Kentucky — continued to rebound from pandemic lows.

In the United States as a whole, however, the number of births has plateaued after a modest increase following the worst of the pandemic, according to preliminary data from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Births increased in only 15 states from 2021 to 2022, compared with growth in 43 states between 2020 and 2021. More detailed statistics, which could shift slightly, are due for release June 1.

Overall, the new data shows the continuation of a long-term trend toward fewer births in the United States, said Phillip Levine, an economics professor at Wellesley College who studies birth trends. Births were down more than 650,000 or 15% over the past 15 years.

“We’re back where we started before COVID hit,” Levine said. “Births are still declining, albeit perhaps at a slower pace. There certainly is no reason to stop sounding the sirens on the long-term decline in births in the United States.”

Without an increase in immigration, that trend could mean an older population, a smaller workforce and?diminished economic productivity. That’s true even in Texas, where second-generation immigrants and women under 30 in general are increasingly postponing parenthood.

Illinois, Pennsylvania and Michigan, states where the overall population is declining, experienced the largest decreases in births.

In Texas and Florida, the number of births was up 4% in 2022 compared with 2021. In terms of overall population, they are the fastest-growing states as of mid-2022, according to the latest U.S. Census Bureau estimates.

In Texas, births increased by almost 16,000, compared with an increase of 5,400 between 2020 and 2021. In Florida the increase was about 8,200 compared with 6,600 the previous year.

Other states with increases between 2021 and 2022 were:

- Georgia (about 1,900),

- North Carolina (1,200),

- New Jersey (795),

- Arizona (526),

- Virginia (361),

- Tennessee (359),

- Delaware (353),

- South Carolina (302),

- Maryland (272),

- ?Kentucky (262).

- Kansas, Idaho and Alaska had increases of fewer than 100 each.

Nationally, there were 700 more births in 2022 than there were in 2021. Between 2020 and 2021, the number of births increased by 51,000.

Florida’s increase in births is partly a reflection of more people moving to the state, but also higher birth rates after a dip during the depths of the pandemic, said Stefan Rayer, population program director at the University of Florida’s Bureau of Economic and Business Research. Even in Florida, however, the long-term trend is bending downward, with birth rates for Black, white and Hispanic women well below the peaks in the mid-2000s.

Arizona’s increase of about 500 births, about half the number of the previous year’s increase, may already be turning into a small decrease in early 2023, State Demographer Jim Chang said.

Illinois had the biggest drop in births, about 4,400, almost four times the previous year’s drop of 1,100. Pennsylvania and Michigan (both about -2,800) and New York (-2,300) saw births decline in 2022 after increases between 2020 and 2021.

It was a different story between 2020 and 2021, when New England states saw the largest increases. New Hampshire, Connecticut and Vermont had the largest percentage increases, according to final 2021 birth data released earlier this year.

Only North Dakota has bucked the overall trend of fewer annual births since 2007. Despite a drop in 2022, the state still had about 800 more births in 2022 than it did in 2007. As North Dakota’s fracking industry in the Bakken Formation has grown in that time, it has attracted more young people of childbearing age, said Kevin Iverson, a demographer in the state Department of Commerce.

Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott Greenberger for questions: [email protected]. Follow Stateline on Facebook and Twitter.

]]>