Cellist and vocalist Ben Sollee, above, in his "Misty Miles" video, will speak at the Kentucky Bike Walk Summit next month in Lexington. (Ben Sollee)

Acclaimed cellist and native Kentuckian Ben Sollee said he gained a sense of freedom growing up in Lexington on his bicycle. He would hop on it to ride around the neighborhood, no cell phone and little worries with him, not having to be home until dark.?

But as he grew into adulthood and a career as a touring musician across the country and world, traveling by cars, planes and trains, he began to feel disconnected from the “experience of music and being in a place” given his fast-paced, time-consuming travel.?

In 2009, he was booked to perform at the Bonnaroo music festival in Tennessee and decided to try getting there via a newly-bought bicycle capable of carrying more than 50 pounds of equipment, supplies and, of course, his cello. He remembers the roughly 330 miles between Lexington and the music festival as “very hot” as he pedaled across the Cumberland Plateau, playing several smaller shows along the way.

“The wonderful thing about being on a bicycle is you can only ride so far and so fast, especially when you’re hauling so much gear,” Sollee told the Lantern. “I found myself being very present.”?

He said over the next five years he would ride about 6,000 miles on his bike as he incorporated it into some of his tours. The bicycle, he said, provides him not only a healthy way to get around but also a way to be more present in his community and with himself.?

It’s that message of how bicycling has improved his life and its connections with his music that he hopes to bring as one of the keynote speakers for the Bike Walk Kentucky Summit next month at Transylvania University in Lexington.?

The conference, scheduled for Aug. 15-16, is described by organizers as a gathering of hundreds of Kentucky leaders in and outside of government hoping to brainstorm and envision safer and more numerous walking, hiking and biking routes and facilities across the state. A similar summit took place at the private university in 2018 connected to the nonprofit Bike Walk Kentucky.

Jim Gray, the secretary of the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet and a former Lexington mayor,? will give opening remarks along with current Mayor Linda Gorton. In a statement, Gray said the summit will “promote safe practices and encourage more complete streets to support a safer and more inclusive transportation system that protects all road users.”?

Other keynote speakers at the summit include Bill Nesper, the executive director of the League of American Bicyclists; Angie Schmidt, a writer and expert on sustainable transportation, and tourism and recreation leaders Kalene Griffith and David Wright from Bentonville, Arkansas, a community highlighted by Axios for its investments into the cycling industry.?

Sollee hopes the summit can promote cycling as not only something that’s healthy for Kentuckians and the environment but also something to be celebrated — highlighting the challenges bicyclists face on public streets battling traffic but also the fun it can bring people, too.?

“The biggest thing we could possibly do is just celebrate and promote people that use their feet and bicycles in the community,” Sollee said. “We really have to be very proactive about sharing, not just what a battle it is out there to ride your bicycle on public streets, but also what a joy it is, and how you know how it helps us connect with other people in our community.”

Those interested in attending the summit can register on Bike Walk Kentucky’s website.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Andrew Kenner donates blood at the Kentucky Blood Center on May 22, 2024, in Lexington. His son, Adam, donated blood at the same time and his wife donated later in the day. (Kentucky Lantern photo by Arden Barnes)

FRANKFORT — A Taylor Swift ticket giveaway worth thousands of dollars and aimed at incentivizing more people to donate blood worked, Kentucky Blood Center donor numbers show.??

From May 28 through June 29, anyone who donated at any Kentucky Blood Center location was entered to win two Eras Tour tickets for Nov. 3 in Indianapolis.?

The anatomy of Kentucky’s blood supply, and why more need to donate

The winner, who has not yet been announced, will also get a $500 gift card to help with travel. Seat Geek shows tickets for that day range from $1,988 to $6,486 apiece.?

Blood donors also received Swift-themed t-shirts and friendship bracelets, which are often exchanged by people in the Swift fandom at concerts.

During the month of the giveaway, 1,592 first-timers donated with the Kentucky Blood Center. That’s up from 929 during the same time period in 2023 and 799 during the same time period in 2022.?

During the giveaway time period, the center saw 9,233 total registrations, up from 8,479 in 2023 and 7,537 in 2022.?

The number of young donors dipped dramatically during the pandemic, in part because mobile drives couldn’t go into schools. In recent years, schools have allowed mobile blood drives to resume.

Still, donations haven’t reached pre-pandemic levels yet, which staff say is possibly because of lingering discomfort due to COVID-19.

A big goal of the Swift giveaway was to incentivize younger donors, KBC spokesman Eric Lindsey told the Lantern.?

While age data isn’t yet available, the increase of first-time donors “leads us to believe that we met our goal in terms of bringing in, bringing in a new crowd,” Lindsey said Monday.?

“The fact of the matter is, we brought in people who have never donated blood before,” he said.?

Donor data from the month of the giveaway shows that about 17% of all donors were first time donors. That’s more than 6% higher than the past two years.?

With any increase in new donors, the rate of deferrals is expected to increase. A deferral is when someone is turned away for issues like low iron or failure to meet other eligibility criteria.?

The deferral rate did increase to 15% during the month of the giveaway, up from around 13% the past two years during the same time. Despite this, Lindsey said, the rate of deferral was “honestly not as high as we thought it would be.”?

Thanks to the increase in donations, the center was able to keep a steady supply of blood despite the expected decrease in donations over the July 4 holiday, when donation centers were closed.?

“We did so well in terms of total blood collected,” Lindsey said, “that we just went through that (holiday) period, and yet we still have a really healthy supply.”?

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

A poster, handprinted by Just a Jar Design Press in Marietta, Ohio, will be available for sale. (Appalshop)

Appalshop has announced the lineup for Seedtime on the Cumberland June 1 in Whitesburg.

The free annual festival will feature live music, jam sessions, food and art, including a quilt exhibit hosted by the Southeast Kentucky African American Museum and Cultural Center.

Performers for the 2024 festival include Sunrise Ridge, John Haywood, Jay Skaggs, Randy Wilson, The Heavenly Voices (from Williams Chapel AME Zion Church in Big Stone Gap, Virginia), Mike Ellison, Coaltown Dixie, Matthew Sidney Parsons featuring Logan Cooper, and Sarah Kate Morgan.

The punk show will feature the Laurel Hells Ramblers, Appalachiatari, Kareem Ledell, geonovah, Dungeon, LIPS, Hedonista and Killii Killii.

The main event will be held from 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. June 1 at Appalshop’s Solar Pavilion at 91 Madison Avenue in downtown Whitesburg. The? punk show will begin at 7 p.m. at the Whitesburg Skate Park, 122 Arizona Avenue.

Founded in 1969, Appalshop is an arts, media and education nonprofit based in Whitesburg that seeks to document and revitalize the traditions and creativity of? Appalachia. A news release says Seedtime on the Cumberland “furthers Appalshop’s mission by celebrating Appalachian culture, music, and stories that commercial media won’t share; challenging stereotypes; supporting grassroots efforts to achieve justice and equity; and celebrating cultural diversity.”?

For more information, call (606) 633-0108, visit appalshop.org/seedtime, or email [email protected].

]]>The Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame will honor six new members Monday evening at The Kentucky Theatre in Lexington.

The ceremony begins at 7 p.m. Doors open at 6. p.m. The event is free and open to the public.

This year’s living inductees are:

George C. Wolfe, “titan of the American theatre,” according to The New Yorker.

The playwright and three-time Tony award winning director of plays and movies grew up in Frankfort. Among Wolfe’s many creative achievements, he directed Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America: Millennium Approaches.” Wolfe’s “Rustin,” now on Netflix, is a biography of Bayard Rustin, whose contributions to the civil rights movement have been obscured because he was gay.

Fenton Johnson, whose “Scissors, Paper, Rock” was the first major fiction about the AIDS crisis’ in rural America.

Johnson’s fiction and nonfiction are steeped in the culture and history of his native Nelson County and his family’s association with the Abbey of Gethsemani. His novels include “The Man Who Loved Birds” and his nonfiction includes “Geography of the Heart: A Memoir” and “Keeping Faith: A Skeptic’s Journey among Christian and Buddhist Monks.”

Mary Ann Taylor-Hall, a transplant to Kentucky whose fiction and poetry are suffused with the landscape and life of her rural Harrison County home.

Her novel “Come and Go, Molly Snow” is about Bluegrass music and a gifted fiddler’s struggle after a tragic loss sends her into the care of two older women on a small farm. “At the Breakers,” set in a hotel under renovation in coastal New Jersey, plumbs family and personal renewal.

The posthumous inductees are:

- Mary Lee Settle (1918-2005), a National Book Award winner for her novel “Blood Tie.” Spent her childhood in Pineville and was a founder of the annual PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction.

- Paul Brett Johnson (1947-2011), a landscape painter who wrote and illustrated children’s books, including “The Cow Who Wouldn’t Come Down” and “Farmers’ Market” inspired by Lexington’s farmers’ market.

- Billy C. Clark (1928-2009), a writer of? prose and poems who grew up in Catlettsburg. Time magazine said his autobiography is “as authentically American as Huckleberry Finn.”

Also, the second Kentucky Literary Impact award will be presented to the late Mike Mullins, who was director of the Hindman Settlement School from 1977 until his death in 2012. As director, he built the annual Appalachian Writers Workshop into a nationally known program and promoted the careers of many Kentucky writers.

The Hall of Fame was created by the Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning in 2012 to recognize outstanding writers with strong ties to Kentucky, according to a release from the Lexington nonprofit.?

Hall of Fame members are chosen by committees at the Carnegie Center and the Kentucky Arts Council that include accomplished Kentucky writers.

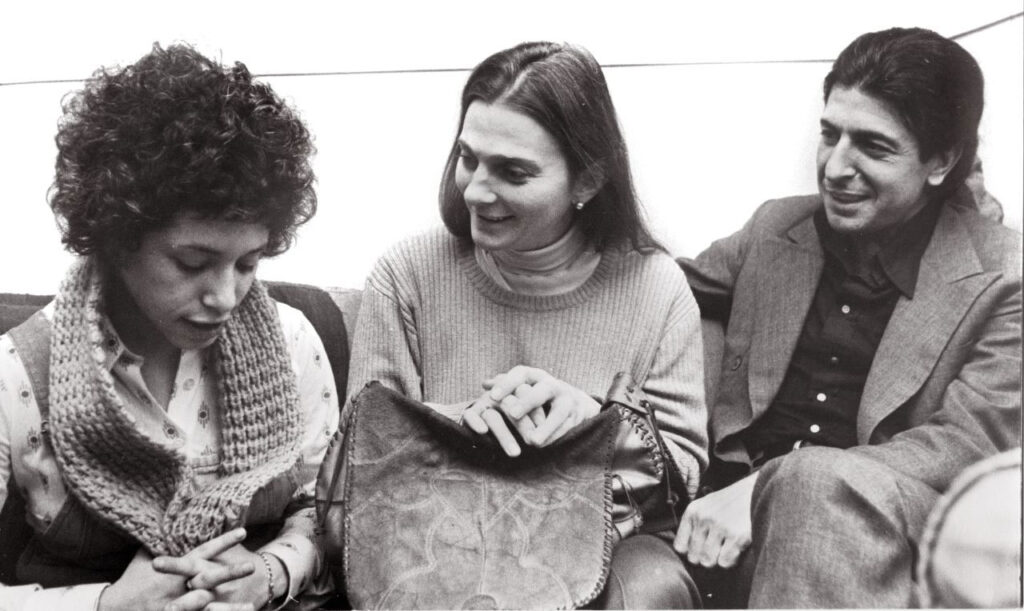

]]>Charlotte Henson, with her son, Robby, and daughter, Heather, at the theater in Danville.

Charlotte Hutchison Henson, the matriarch of the historic Pioneer Playhouse in Danville, has died. She was 93.

Charlotte Henson, with her late husband, Col. Eben Henson, brought Broadway to the Bluegrass by establishing what is now Kentucky’s oldest outdoor theater. It has attracted hundreds of young actors over the years, including John Travolta, Lee Majors, Jim Varney and Bo Hopkins and will be celebrating its 75th season this summer.

Charlotte shared her husband’s vision of the Playhouse and continued his legacy after he died in 2004, said Mike Perros, who was mayor of Danville from 2014 to 2022 and longtime board chairman of the theater.

Perros gave her the nickname “Iron Butterfly.”? “I called her that because she was tough as could be. She was light on her feet but could be all over the place at the theater. She was graceful but could get her message across. She was delightful yet so strong. She cared about that place.”

Charlotte Henson was producer and president of the Playhouse’s board of directors when she died Feb. 13 at her home on the grounds back of the historic theater.

Her daughter, Heather, said her mother had suffered a series of mini-strokes but had been able last summer, as she did every summer for decades, to sing for the patrons before the show. ? Her repertoire never varied, and she would start off her set with “Follow the Drinking Gourd.” The noted folk singer and archivist, John Jacob Niles, called Charlotte’s voice one of the purest he had ever heard.

Charlotte was born on Jan. 3, 1931 and raised on a farm on the Boyle-Mercer County line.

As a youth, she was praised for her voice. After graduating from Burgin High School, she studied music at Transylvania College (now University) in Lexington. After college, she taught music in North Carolina and later was the choir director of the First Christian Church in Danville.

Charlotte first met Eben Henson when she attended an early performance of his fledgling theater at Darnell State Memorial Hospital. He used a free auditorium at the site for his plays, where Northpoint Training Center is now located.

Later, Eben met Charlotte and her mother for lunch at a drugstore soda fountain booth in downtown Danville. He asked Charlotte for a date. Charlotte’s mother kicked Eben in the shin to signal disapproval but Charlotte already had said yes.

In the early years of their marriage, the Hensons saw big-name movie stars flock to their area of the state to star in MGM’s “Raintree County.” Charlotte was a featured extra in the film. The distinctive gingerbread ticket office at the Playhouse was taken from the set of the movie.

Charlotte worked hard with Eben to make the theater go. She also raised four children, all of whom grew up in the theater. Robby Henson today is artistic director, Heather is managing director. When Eben,

known as “the Colonel,” died in 2004, daughter Holly took over the helm of running the theater. It flourished under her leadership. But she died unexpectedly in May 2013 from breast cancer. Her husband, Tom Hansen, is the theater’s chef today. Another son, Eben David, has contributed musically and in other ways to the theater.

The theater also has been guided over the years by a board of directors and influential emeritus board members like the late Gov. Brereton Jones and Lexington businessman and philanthropist Warren Rosenthal.

Charlotte Henson was named Danville’s Arts Citizen of the Year in 2006. She donated space in the old Henson Hotel building for the Danville/Boyle County African-American Historical Space to have a home for meetings, exhibits and archives. She was a lifelong member of the First Christian Church of Danville.

Tori Kenley, office manager for Pioneer Playhouse, said she will miss “Miss Charlotte.”??

“She would come by every morning about 10:30 to say hi and ask how things were going.? She always took pride in the kitchen and was always working with the gift shop,” said Kenley. “Miss Charlotte was very much involved.”

Daughter Heather said it will be difficult to run the theater without her mom, “but as we always have said, ‘The show must go on.’? We will.”

Stith Funeral Home in Danville is handling arrangements. Visitation at the funeral home will be from 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. Feb. 22 and the funeral will be held at 1 p.m. Feb. 23 at the First Christian Church in Danville.

Donations may be made in Charlotte’s name to Heritage Hospice of Danville or to Pioneer Playhouse, both of which are non-profit organizations.

Lexington, the inspiration for Big Lex, the Blue Horse, was born in 1850 and was the greatest Thoroughbred sire of his time. (City of Lexington)

In honor of the 250th anniversary of its founding next year, Lexington is seeking proposals for an outdoor work of art to be placed in the Robert F. Stephens Courthouse Plaza.

“Lexington has a long history with the arts, and a new work of art in the heart of downtown for our city’s 250th anniversary provides a meaningful connection between our early identity as the ‘Athens of the West’ and the cultural legacy that we are building,” said Mayor Linda Gorton.

The 250 Lex Commission is inviting professional and practicing artists residing in the United States to submit qualifications to propose a permanent, unique, 3D artwork in recognition of the city’s anniversary, according to a news release.

A a prominent outdoor site along Main Street in front of the Robert F. Stephens Courthouse Plaza is the selected site for the permanent artwork, according to the release which said it will be “the largest work of public art ever commissioned by the City of Lexington.”

Artists and design teams interested in this project can access the official request for qualifications (RFQ) on the 250 Lex Commission website. Artists must submit their qualifications through CAFé – Call For Entry. All interested and qualified applicants must submit qualifications by 11:59 p.m. MST – Mountain, Thursday, February 29 (in Lexington, 1:59 a.m. EST-Eastern, Friday, March 1).

A selection committee composed of City of Lexington personnel, artists, arts professionals, and other community stakeholders will review the credentials of professional, practicing artists and design teams that can demonstrate experience in successfully executing large-scale public sculpture projects. Entries not meeting requirements will not be considered.

Upon review of all qualified RFQs, three finalists will be invited to submit a proposal for the design of a site-specific public artwork. Finalist proposals should represent a unique commission in ample detail.

For more information, go to https://www.lexingtonky.gov/250lex.

]]>KET will debut "Becoming bell hooks" on Feb. 27 and 29. (KET)

KET will celebrate the February premiere of its documentary “Becoming bell hooks” with preview screenings in Louisville and Lexington.

A KET release says the documentary “explores?the life and legacy of Kentucky-born author bell hooks, who wrote nearly 40 books and whose work at the intersection of race, class and gender serves as a lasting contribution to the feminist movement.

“The one-hour film examines bell’s childhood in Hopkinsville, her return to Kentucky in the early 2000s to join the faculty at Berea College, and how her connection to Kentucky’s ‘hillbilly culture’ informed her belief that feminism is for everybody,” says the release.

The film features selections from hook’s work read by Academy Award winner Octavia Spencer and includes interviews with friends and family, including feminist activist Gloria Steinem, Kentucky writers Crystal Wilkinson and Silas House, her younger sister Gwenda Motley and many others.

Steinem said bell was “one of the most universal writers and universal people” who made the feminist movement more accessible to all by going beyond issues of gender, race, class and geography. “It’s hard to imagine anyone who wouldn’t be enchanted, educated and made happier by her books.”

“Becoming bell hooks“?is a KET production, produced by Elon Justice and Sarah Moyer. It is funded in part by the KET Endowment for Kentucky Productions.

The documentary will air on KET at 9/8 p.m. Feb. 27 and Feb. 29.

Free preview screenings will be held at:

6:30 p.m. Feb. 20 at the Lyric Theatre & Cultural Center ?in Lexington.

7 p.m. Feb . 22 at the Speed Art Museum in Louisville.

To RSVP for a screening or find more information, visit KET.org/bellhooks.

This story has been updated. An earlier version contained errors in the dates of the preview screenings.

]]>Rosalynn Carter’s legacy includes her support for Habitat for Humanity. She helped her husband Jimmy frame houses across the country for the charity. (Photo by Chris Graythen/Getty Images)

Former first lady Rosalynn Carter has died, according to the Carter Center, leaving a rich legacy of championing mental health and women’s rights.

She will be buried at the ranch house in Plains she and former President Jimmy Carter built in 1961. She died Sunday just days after the family announced she had entered hospice at the home.

She was married for 77 years to Jimmy Carter, who is now 99 years old and entered hospice early this year.

“Rosalynn was my equal partner in everything I ever accomplished,” Jimmy Carter said in a statement on the center’s website. “She gave me wise guidance and encouragement when I needed it. As long as Rosalynn was in the world, I always knew somebody loved and supported me.”

Tributes poured in from across the political spectrum Sunday, a testament to her broad popularity that transcended partisan politics and her enduring contributions to causes and charities that stoked her passion.

President Joe Biden and first lady Jill Biden on Sunday were at Naval Station Norfolk in Norfolk, Virginia, participating in a Friendsgiving dinner with service members and military families from the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower and the USS Gerald R. Ford.

“Time and time again, during the more than four decades of our friendship – through rigors of campaigns, through the darkness of deep and profound loss – we always felt the hope, warmth, and optimism of Rosalynn Carter,” the president said in a statement. “She will always be in our hearts. On behalf of a grateful nation, we send our love to President Carter, the entire Carter family, and the countless people across our nation and the world whose lives are better, fuller, and brighter because of the life and legacy of Rosalynn Carter.’’

Georgia Democratic Sen. Jon Ossoff said Georgia and the country are better places because of Carter’s contributions.

“A former First Lady of Georgia and the United States, Rosalynn’s lifetime of work and her dedication for public service changed the lives of many,’’ Ossoff said. “Among her many accomplishments, Rosalynn Carter will be remembered for her compassionate nature and her passion for women’s rights, human rights, and mental health reform.’’

Georgia Republican Gov. Brian Kemp paid tribute to her, recalling her service as Georgia’s first lady during Jimmy Carter’s term as governor starting in 1971.

“A proud native Georgian, she had an indelible impact on our state and nation as a First Lady to both,” Kemp said in a statement. “Working alongside her husband, she championed mental health services and promoted the state she loved across the globe. President Carter and his family are in our prayers as the world reflects on First Lady Carter’s storied life and the nation mourns her passing.’’

Former President Donald Trump said on X that he and his wife Melania joined in mourning Carter.

“She was a devoted First Lady, a great humanitarian, a champion for mental health, and a beloved wife to her husband for 77 years, President Carter,” said Trump.

Georgia GOP Congressman Rick Allen posted on the X social media platform: “Rosalynn was a beloved Georgian and dedicated her life to serving others. Our nation will miss her dearly, but her legacy will never be forgotten.”

Former U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi called Carter “a saintly and revered public servant” and a leader “deeply driven by her profound faith, compassion and kindness.”

Pelosi, a California Democrat, recalled how Carter, while her husband was serving as Georgia governor, was moved by the stories of Georgia families touched by mental illness and took up their cause, despite the stigma of the time.

“Later, First Lady Carter served as honorary chair of the President’s Commission on Mental Health: offering recommendations that became the foundation for decades of change, including in the landmark Mental Health Systems Act,” Pelosi said. “At the same time, First Lady Carter was a powerful champion of our nation’s tens of millions of family and professional caregivers.”

The eldest of four children, Rosalynn was born at home in Plains on Aug. 18, 1927. One of her best childhood friends was Ruth Carter, Jimmy’s younger sister. Jimmy Carter’s mother, Lillian, was a nurse who treated Rosalynn’s father when he was ill with leukemia.

Rosalynn enrolled at Georgia Southwestern College in 1945 after she graduated from Plains High School with honors.

Jimmy Carter was home on leave from the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis that fall when he asked her to go to a movie. By Christmas he’d proposed to her, but she turned him down because things were moving too fast for her. He soon asked again and the couple married at Plains Methodist Church July 7, 1946, a month after Jimmy graduated from Annapolis.

As Jimmy Carter climbed the Navy’s ranks, the couple started a family with sons John William arriving in 1947, James Earl III (“Chip”) in 1950, and Donnell Jeffrey in 1952. Daughter Amy was born in 1967.

Carter was accepted into an elite nuclear submarine program, and the young family then moved to Schenectady, N.Y. But when his father fell ill, Jimmy left his commission and moved back to Plains to take care of the family’s peanut business.

Rosalynn was an active campaigner during her husband’s political climb, beginning with his run for state senator in the early 1960s. By the time he was elected president in 1976, she vowed to step out of the traditional first lady role.

Five weeks after Inauguration Day, the President’s Commission on Mental Health was established with Rosalynn serving as honorary chairperson. The Mental Health Systems Act that called for more community centers and important changes in health insurance coverage, passed in 1980 at her urging.

In 1982, the couple founded the Carter Center in Atlanta, with a mission to “wage peace, fight disease and build hope.” She later founded the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving at the school now known as Georgia Southwestern State University, her alma mater. The institute was renamed the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers in 2020.

She was also an active partner in her husband’s philanthropic support for Habitat for Humanity, often joining him in framing houses for charity.

Three months after Jimmy entered hospice in February, the Carter family announced Rosalynn had dementia. She entered home hospice Nov. 17.

Rosalynn Carter is survived by her children — Jack, Chip, Jeff, and Amy — and 11 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren.

The Carter family requests that in lieu of flowers people consider a donation to the Carter Center’s Mental Health Program or the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers.

This story is republished from Georgia Recorder,?a sister publication of Kentucky Lantern and part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity.?

]]>Exile (Courtesy of Exile)

Exile fans, KET needs you.

The Kentucky public television network is producing a documentary about the Kentucky band, which formed in Richmond in 1963 and achieved national success in 1978 with their chart-topping hit “Kiss You All Over.”

KET would appreciate the public’s help in tracking down old photographs, home movies (8mm or super 8mm footage) or other memorabilia of the band, particularly from the 1960s and 1970s. Both analog or digital content is welcome, according to a news release.

If you have Exile memorabilia you’d be willing to share — temporarily; it will be returned — please, contact producer Tom Thurman at [email protected]. ?

]]>Part of the cover of "Hawks on Hawks," published by the University Press of Kentucky. (UK photo)

A book published by the University of Press of Kentucky has made a list of the 100 greatest books about film

“Hawks on Hawks,” comprising author Joseph McBride’s interviews with director Howard Hawks by Joseph McBride, will appear on The Hollywood Reporter’s list of “The 100 Greatest Film Books” and will be celebrated in The Hollywood Reporter magazine and on its website on Oct. 11, according to a news release from the University of Kentucky.

The University Press of Kentucky is a statewide nonprofit publisher of scholarly works, serving Kentucky’s public and seven private colleges or universities and two major historical societies. The press says it is dedicated to the publication of academic books of high scholarly merit as well as significant books about the history and culture of Kentucky, the Ohio Valley, Upper South and Appalachia.

The UK release says the list of “The 100 Greatest Film Books” was chosen by a “blue-ribbon panel” including filmmakers Steven Spielberg and Ava DuVernay, film executives Sherry Lansing and David Zaslav, film book authors Leonard Maltin and Molly Haskell, and cultural tastemakers Maureen Dowd and Roxane Gay.

McBride is the author of 24 books, including the biography “Searching for John Ford” (hailed as “definitive” by The New York Times and the Irish Times), biographies of Frank Capra and Spielberg, three books on Orson Welles, and critical studies of Ernst Lubitsch and Billy Wilder. A former film and television writer as well as a reporter, reviewer and columnist for Daily Variety in Hollywood, McBride is a professor in the School of Cinema at San Francisco State University.

The UK release says: “Hawks on Hawks” draws on interviews that McBride conducted with Hawks (1896-1977) over seven years, giving rare insight into Hawks’s artistic philosophy, his relationships with the stars and his position in an industry that was rapidly changing. Hawks is often credited as being the most versatile of all of the great American directors, having worked with equal ease in screwball comedies, westerns, gangster movies, musicals and adventure films. He directed an impressive number of Hollywood’s greatest stars — including Humphrey Bogart, Cary Grant, John Wayne, Lauren Bacall, Rosalind Russell and Marilyn Monroe — and some of his most celebrated films include “Scarface” (1932), “Bringing Up Baby” (1938), “The Big Sleep” (1946), “Red River” (1948), “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” (1953) and “Rio Bravo” (1959).

“Hawks on Hawks,” which has been published in French, Spanish, Italian, Japanese, Finnish?and in England by Faber and Faber, was also chosen by The Book Collectors of Los Angeles as one of the “100 Best Books on Hollywood and the Movies.” The French director Fran?ois Truffaut, whose interview book with Alfred Hitchcock is a landmark in film studies, said, “I read ‘Hawks on Hawks’ with passion. I am very happy that this book exists.” In its new edition, this classic book is both an account of the film legend’s life and work and a guidebook on how to make movies.

“Howard Hawks was one of the great storytellers on film,” McBride said. “I sought him out because I wanted his advice on how to write screenplays. I continued talking with him in his home or in public venues for the rest of his life. He was a marvelous raconteur and a wise and witty man who taught me much about film. Toward the end of our time together, I realized I had the makings of an interview book. I am pleased that so many people have found it valuable and entertaining.”

The Hollywood Reporter and AFI FEST will collaborate on a celebration of the authors of books on the list, which will be held during AFI FEST ?Oct. 28, at the TCL Chinese Theaters in Hollywood.

]]>Taylor Swift performs on opening night of The Eras Tour at State Farm Stadium in March 2023 in Arizona. (Kevin Winter/Getty Images for TAS Rights Management)

There’s no question what motivated state Rep. Kelly Moller to push for changes in Minnesota law on concert ticket sales.

“Really, it was the Taylor Swift debacle for me,” she said.

A self-professed Swiftie, the Democrat found herself among millions of other Americans unable to buy tickets last year to Swift’s Eras Tour.

She preregistered for tickets, but never received a code to buy them. And on the day sales went live online, she sat by as friends with codes got bumped out of the ticket queue for no apparent reason.?Then Ticketmaster’s website crashed.

The ordeal convinced her that the concert ticket industry warrants more government oversight.

“I do think a lot of that is better served at the federal level, but that said, there are things we can do at the state level,” she said.

Moller introduced a bill this year that would force ticket sellers to disclose the full cost of tickets, including fees, up front to buyers in her state. It also would ban speculative ticketing — a practice in which resale companies sell tickets they don’t yet own.

The bill stalled, but Moller expects it to be reconsidered next year. It is part of a wave of legislation considered in more than a dozen states this year following the unprecedented disaster in the run-up to Swift’s Eras Tour, which is on pace to be the highest-grossing tour in history.

Swift and her legions of fans were outraged when Ticketmaster’s website crashed last November as it faced unprecedented demand from fans, bots and ticket resellers ahead of her tour.?Social media blew up over the fiasco, and news organizations published story after story. It sparked bipartisan legislative proposals in Congress, though no bill has become law yet.

That’s led state legislatures to step in: Lawmakers of both parties across the country introduced new bills this year to regulate concert and live event ticket purchasing.

Ticketing fights are far more contentious than anyone anticipates. Each side of the market likes to blame the other side, and consumers are stuck in the middle.

– Brian Hess, executive director of Sports Fans Coalition

It’s a rare bipartisan issue in statehouses. But lawmakers are learning how complicated — and controversial — the world of online ticketing is. In several states, legislators are caught in the middle between companies like Ticketmaster and secondary sellers such as StubHub.

“There are a lot of issues that beg for a national focus, a national solution. But because of the political dynamics in Washington, D.C., we haven’t gotten very many solutions. … So states believe they have to act,” said California state Sen. Bill Dodd, a Democrat.

Dodd sponsored a bill this year that would ban so-called junk fees on tickets — fees tacked onto the base price that lawmakers view as deceptive. The proposal targets other services, including hotel and resort fees, but Dodd said concerts were a major driver. President Joe Biden called out junk fees in his State of the Union address in February and has publicly praised companies that have committed to transparent pricing, such as Airbnb and Live Nation, Ticketmaster’s parent company.

Dodd said he isn’t hostile to ticket marketplaces such as Ticketmaster and StubHub. He uses those sites to buy tickets to concerts and basketball games. But, he said, consumers should know the full price up front. The White House estimates junk fees cost Americans more than $65 billion per year.

“It’s outrageous,” he said, “and I think Californians are sick and tired of dishonest fees being tacked onto just anything.”

Dodd’s bill, which was backed by California Democratic Attorney General Rob Bonta, passed the state Senate and is pending in the Assembly. It is one of several ticketing bills considered by Golden State lawmakers this session.

The state Senate unanimously passed a proposal from Republican state Sen. Scott Wilk that he said targets the “stranglehold” some companies have over sales. The bill would prohibit exclusivity clauses in contracts between a primary ticket seller such as Ticketmaster and an entertainment venue in California. Wilk said in his news release it would allow artists to work with other ticket sellers without the fear of retaliation from large ticket sellers — and ultimately reduce fees for consumers. It’s in committee in the Assembly.

‘The states are where it’s at’

Earlier this year, the Colorado legislature passed a bill that would have required sellers to fully disclose the total cost of event tickets, prohibited vendors from raising prices during the buying process and banned speculative ticketing.

But Democratic Gov. Jared Polis vetoed the act in June, saying it could prevent competition and “risk upsetting the successful entertainment ecosystem in Colorado.”

Chris Castle, an entertainment lawyer who tracks ticket legislation across the country, said the Colorado veto illustrates the industry’s ability to sway public officials.

Polis referenced concerns he heard from the National Consumers League and the Consumer Federation of America. Both of those consumer advocacy groups have received funding from secondary ticket marketplaces such as StubHub, the music publication Pitchfork reported.

“It’d be easy enough to say, ‘Well, I heard from the stakeholders, and I thought these guys had the better argument.’ But he didn’t say that,” Castle said of Polis. “He starts talking about these groups. And sure enough, it turns out, they’re all on the take.”

Conor Cahill, the governor’s spokesperson, did not answer questions about the influence of ticket marketplaces on the veto, but said Polis will apply a “consumer-first lens” to future legislation on the issue.

The National Consumers League has no problem being associated with groups like StubHub, said John Breyault, the organization’s vice president of public policy, telecommunications and fraud. He said the group shares a common belief with resellers that the marketplace needs more competition, not less. But it still disagrees on some specific issues, he said.

“There are problems at every level of the industry including in the secondary market that we are trying to address through both our advocacy at the state level and our advocacy at the federal level,” Breyault said.

Bills in several states backed by StubHub aim to protect so-called transferability of tickets — that is, the customers’ right to pass on or resell tickets they purchase.

Six states — Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, New York, Utah and Virginia — currently protect the right of fans to transfer or sell tickets. Without that right, some advocates say Ticketmaster’s terms and conditions can ban transferring tickets or require that they be resold on their own platform.

StubHub makes no secret of its efforts to educate and persuade state lawmakers.

“The states are really where it’s at in a lot of ways,” said Laura Dooley, the company’s head of global government relations.?“Our industry right now is almost exclusively regulated at the state level.”

This year, the company has tracked nearly 70 ticketing bills proposed across 25 states. Dooley said many state lawmakers introduce new regulations with good intentions, but don’t always understand the industry.

As an example, she pointed to state efforts to ban bots — software that can bypass security measures in online ticketing systems and buy tickets in bulk faster than humans.

Ticketmaster cited bots as a major cause of the Eras Tour fiasco. Bots are banned by federal law, though that regulation only has been enforced once since 2016, according to the Federal Trade Commission. Dooley said StubHub isn’t opposed to state bot bans, but does push legislators to consider enforcement measures in crafting their bills. That’s because regulators need cooperation from the industry and access to ticketing software to monitor for bots, Dooley said.

Dooley contends some lawmakers’ proposed solutions don’t target root causes, including the unique way live event tickets are sold, generally through exclusive deals with one retail platform.

“When you have millions and millions of people wanting to buy a product and they’re being asked to buy that product at the same time on the same day through an exclusive retail provider — in this case Ticketmaster and in many cases Ticketmaster — that system is going to be overloaded, right? And it’s going to be a frustrating experience,” Dooley said.

In a statement, Ticketmaster said the company was working with lawmakers across the country on “common-sense” ticketing reform measures. The company said it supports requirements for all-in ticketing pricing, bans on speculative ticketing and giving artists more say in how their event tickets are resold.

Brian Hess, executive director of the nonprofit fan advocacy organization Sports Fans Coalition, pointed out thatlawmakers have a variety of interests to consider: the primary ticket markets like Ticketmaster, the artists, the consumer, and secondary markets like StubHub.

“Ticketing fights are far more contentious than anyone anticipates,” he said. “Each side of the market likes to blame the other side, and consumers are stuck in the middle.”

The Sports Fans Coalition is in part funded by secondary marketplaces like StubHub and lobbies on ticket legislation across the country.

Hess said federal regulators should not have allowed the 2010 merger of Live Nation, an event promoter and venue operator, with Ticketmaster, a ticket provider.

“They are the monopoly in the industry,” he said. “They were the ones that botched Taylor Swift’s tickets, and they’re the ones that continue to have ticket sale problems when they launch new shows.”

A bipartisan focus

Texas Republican state Rep. Kronda Thimesch said she saw firsthand how bots can distort the marketplace and prevent customers from purchasing tickets.

That’s what she blamed for her own daughter’s unsuccessful attempts to buy Swift tickets last year.

“Fans then have to resort to paying hundreds, if not thousands, over face value to resellers in order to see their favorite artist,” she said.

That’s why she introduced a bill banning ticket-buying bots in Texas, which was signed into law by Republican Gov. Greg Abbott.

Thimesch noted that ticket issues aren’t just a problem for Swift fans — country star Zach Bryan named his December live album “All My Homies Hate Ticketmaster.” Thimesch said she is open to exploring more ticketing legislation when the Texas legislature reconvenes.

More than 1,500 miles away, Massachusetts Democratic state Sen. John Velis has a similar outlook. He’s interested in diving deep into the world of ticketing. But he’s starting off small.

“I think the art, if you will, of legislating is you kind of go little by little,” he said. “I think ticket pricing is a great and very logical place to start.”

Velis introduced a bill that would require upfront transparent ticket pricing and ban “dynamic pricing,” a practice in which sellers adjust prices based on demand. While he’s interested in eventually exploring ride shares or other services, his legislation is so far focused on concert and live event tickets, he said.

Before the Eras Tour mess, Velis said he got interested in the issue after hearing constituents and co-workers complain about exorbitant fees on live event tickets. Tickets advertised for $100 can sometimes end up costing double that once all the fees are tacked on, he said.

“I just thought to myself, ‘That is so incredibly wrong,’” he said. “If someone wants to spend their hard-earned money at $10,000 a ticket to go see Taylor Swift or Jay-Z or the Boston Celtics, giddy up. But I just want that consumer to know going into that initial transaction that they’re going to be spending $10,000.”

Velis said his bill should receive a hearing soon in the state Senate.

Jurisdictional bounds are likely to prove complicated, he acknowledged. After all, consumers often buy tickets for events in other states. But he said his bill is solely aimed at protecting consumers — a notion he says is hard to oppose.

“In my experience, this is without a doubt a bipartisan issue,” he said. “I’ve experienced nobody raising a concern from a partisan politics standpoint.”

Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: [email protected]. Follow Stateline on Facebook and Twitter.

]]>Appalshop in downtown Whitesburg. (Appalshop photo)

Appalshop, a community media and arts organization dedicated to preserving and sharing the rich cultural heritage of Central Appalachia, will host its 37th annual Seedtime on the Cumberland Festival on June 16–17, the first since the devastating 2022 summer flood.

This free festival featuring music, art, dance, film, local crafters, and food will be held across downtown Whitesburg in four different venues. The program features a passport page, and attendees will be entered to win a prize if they receive a stamp from?each location.

Performers for the 2023 festival include Dori Freeman, Adeem the Artist, the Don Rogers Band, Sparky & Rhonda Rucker, Travis Stuart, L.I.P.S., and many more. Beyond performances, there will also be a dance workshop, a banjo workshop, and several film showcases, including a screening of Appalshop’s newest film, “Wiley’s Last Resort.”

In the spirit of community arts, the festival provides a space for regional artists, crafters, authors, and organizations to showcase their talents and wares.

Seedtime on the Cumberland furthers Appalshop’s mission through the celebration of Appalachian culture, music and stories. ?This festival also challenges stereotypes, supports grassroots efforts to achieve justice and equity, and celebrate cultural diversity, according to a news release from Appalshop.

For more information, call (606) 633-0108 or email [email protected].

Riverside Cemetery in Perry County, where members of the author's family are buried. (Photo by Tracy Staley)

This story was first published in The Daily Yonder on May 21, 2021 and is is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

While their friends are cannonballing into the city pool this weekend, my sons will spend the day in an Eastern Kentucky cemetery, placing flowers on the graves of relatives they never knew.

We are going back home on Decoration Day — a folk tradition practiced by generations of Appalachians and Southerners dedicated to visiting cemeteries where their families are buried to clean and decorate their graves, and often to attend a religious service and dinner on the cemetery grounds.

Like most who grew up in Eastern Kentucky, I’ve been practicing various rites of Decoration Day all my life. I loved the reunions, playing with my cousins, and filling plates of food and desserts. Although, I admit: I have often seen the other parts of Decoration Day as an unnecessary effort, one I had little interest in carrying on. What good was there in spending money on artificial flowers for people who would never know you made the gesture?

Yet this year, something changed. Perhaps it was turning 40, or the reckoning of the pandemic, or both, that made Decoration Day seem urgent and important not only to observe, but to pass down to my children.

As my perspective changed, my interest grew and sent me seeking answers, both historical and personal, about the cultural tradition, its origins, and why I felt a sudden urge to drag my three children to a cemetery on their first week of summer vacation.

What Is Decoration Day?

In Ohio, the streets of my small town are lined with tiny American flags. Living near a military base, with many active-duty and retired U.S. Air Force neighbors, I am keenly aware of the reverence paid to Memorial Day. Each year, I’d find myself asking my friends, “We always called it Decoration Day. We decorated everyone’s graves. Did you?” The answer was, with rare exception, no. Secretly, I worried if somehow I had incorrectly celebrated a patriotic holiday. Was this the same as not knowing I needed to illuminate a flag at night or take it down in the rain? Did we get this wrong? Had we expanded it selfishly to include everyone when we should have been only honoring those who died in battle?

For insight, I turned to the book “Decoration Day in the Mountains,” by folklorist Alan Jabbour, founding director of the American Folklife Center?at the?Library of Congress.

Jabbour’s thorough exploration of Decoration Day relieved me of my concerns and filled me with a new appreciation for history and rituals.

Decoration Day, Jabbour wrote, actually inspired Memorial Day, pre-dating any post-Civil War celebration in the South or North. Before the war, Appalachians and Southerners were already practicing what they called Decoration Day, also called “a decoration,”??which involved an annual “cleaning of community cemeteries, decorating them with flowers, and holding a religious service in the cemetery, often with “dinner on the ground.” Families spent weeks leading up to Decoration Day making buds and petals from bright crepe paper, cleaning the cemeteries.

His research also softened my other silent concern that Decoration Day was tied up in celebrating the Confederacy. Jabbour

explains that two early and unrelated celebrations of the Confederate dead — one in Charleston, South Carolina, and the other in Petersburg, Virginia — both using the word “decoration” and both using flowers, led Jabbour to the conclude that organizers of the events each drew upon an existing tradition.

After reading Jabbour’s book, I called my grandmother, with whom I had tagged along to the cemetery, reunions and flower-buying expeditions. It was she who had carried the duty of Decoration Day to me, and I wanted to know why.

‘I was kindly like your youngins‘?

One question from me about Decoration Day transports my grandmother back to her childhood — and ties me to the generations that came before me.

From the old days?

“Yes.”

It used to be a big day for people. When I was a little girl, my grandma would start in her spare time … and make crepe paper flowers. She usually made them out of bright red and turquoise and bright pink and white crepe paper. They would make a bud, and cut out petals, and take a knife to the petal and scrape the end of it to make it lay down and curl. They would have their wire, and put that bud on the end of the wire, and start with the little petals and tie them on.?

It was about two-and-a-half ?miles to that cemetery. Grandpa would always walk, and grandma would be on the horse. She would have a basket full of fried chicken, maybe fried pies, and cake, just food like that. And me, I was always running. We cut through the hills instead of going on the main road … we’d come down so far out of that hollow and then cut through the hill. When you go through the hills there’s wild honeysuckle, the prettiest orange, and as you go up through there, there are pine trees … and it smells like pine all the way through there. It was where grandma’s babies were buried, ones who died when they were born, and her son who died when he was 21.?

They’d sing, decorate graves, and talk, a lot of them hadn’t seen each other in a month or a few weeks.?

They had a preacher; he always, at least to me, preached too long. I would get so hot and tired that I just wanted to hurry up and get gone. …?

I’ll be honest with you, I was kindly like your?youngins, I never was still.? As far as standing around and watching what everybody did, I just sure didn’t. But I do remember decorating the graves. I think it’s important to decorate.

Hearing her stories made it clear: Decoration Day, for me, was the remembering, linking myself and my children to the generations before us.

As I grow older, and as a pandemic has brought the fragility of life into clear focus, I’m buoyed by the remembering, by the traditions that connect the present, future and past. To quote Alan Jabbour, “At the deepest spiritual level, a decoration is an act of respect for the dead that reaffirms one’s bonds with those who have gone before.”

And so?today, my children will carry the flowers over the hillside to the graves of their great-grandfather, great-great grandparents and other relatives.

We’ll make sure to place a small bouquet on the stone of my grandfather’s little brother, who died as an infant.

They’ll listen to our stories as we walk around the cemetery, and I hope, feel connected to the people who came before them.

They will get hot, tired, and bored.

Like their great-grandmother 80 years before them, they will want us to hurry up and get gone.

But someday, maybe they will want to come back.

![]()

Silas House is inducted as Kentucky poet laureate at the annual Kentucky Writers Day celebration in the state Capitol rotunda in Frankfort. (Photo by Tom Eblen)

LOUISVILLE – Growing up in Eastern Kentucky, author Silas House saw early the power of representation in literature.?

Lead character John-Boy in the award-winning television series “The Waltons,” for example, was his “hero.”?

Here was a young country boy who, like House, dreamed of writing.?

“I didn’t know anybody who wanted to be a writer,” said House, who on April 24 became Kentucky’s new poet laureate. “I especially didn’t even know any boys who would admit to reading.?So I was pretty lonely in the world as a reader, as a boy.”?

In his new post, House feels “an extra layer of responsibility” to represent Kentuckians — and the full spectrum of the human experience, he said in a recent sweeping interview with the Kentucky Lantern.?

People call him many things: Appalachian writer, working class writer, a writer of faith.?

Now, he’s the state’s first openly gay poet laureate.?

“I’m not offended by any of those labels,” the New York Times bestselling author said. “But … the way I think of myself is totally multifaceted.”?

He strives to represent his characters that way, too.?

“Any good writer is fascinated by human beings,” said House, whose awards include the 2023 Southern Book Prize and the Duggins Prize.?

He started studying people in the long holiness church services he attended as a child.?

“I was not allowed to take any toys with me, but I was allowed to take a notebook and pencil,” he said. “I remember studying people during those church services, and I would write … a little character sketch about everybody in the church … when you really look closely at people, it’s hard to see them as one dimensional.”?

Books by Silas House:

- “Clay’s Quilt”

- “A Parchment of Leaves”

- “The Coal Tattoo”

- “Eli the Good”?

- “Same Sun Here” with co-author Neela Vaswani, who also authored “You Have Given Me a Country”

- “Lark Ascending”

- “Something’s Rising” with co-author Jason Kyle Howard, who also authored “A Few Honest Words”?

House has also had work appear in:

‘There is no monolithic gay person.’?

House’s appointment as poet laureate – the first openly gay Kentuckian in the role – comes after a legislative session featuring several?anti-LGBTQ bills.?

Lawmakers banned gender-affirming care for transgender minors amid some bipartisan opposition.?

Additionally, schools can now keep trans students from using the bathroom of their choice and teachers can misgender trans youth.?

Drag shows also came under heat this session, which ended March 30.?

“There are so many people that have felt … belittled and hurt by that legislation,” House said. “It feels like it’s legislation by a very vocal majority of the legislators that doesn’t really line up with the majority of Kentuckians, which, in a way, makes it even more frustrating.”?

House, who’s spoken openly about having a transgender son, said the push for more parents’ rights this session didn’t include parents of LGBTQ+ children.?

“No LGBT person I know is asking for special rights — they’re only asking to be treated equally. The same as parents of LGBT people should be treated like any other parents,” he said. “I think that’s one of the things that the legislation really has illuminated is that the parents of LGBT children are being given less rights than the parents of straight children.”?

He’s focused on being “diplomatic” while representing all Kentuckians in his new role.?

“I know that it’s important especially for young queer people to see me in the public,” he said. “I’m just happy to be out there as an openly gay person and to be visible and to show people that there is no monolithic gay person.”?

Being gay also shouldn’t be politicized, House said.?

“Somebody said to me the other day: ‘Why do you have to be so political about being gay?’” he said. “I’m not the one who politicized being gay. I’m just living my life.”?

‘No agenda’ when writing.?

(Photo provided by governor’s office)

Gov. Andy Beshear praised House’s work when introducing him as the new poet laureate.?

“We are so proud of Silas, who grew up in Kentucky, was educated in Kentucky and now represents our state with such pride,” Beshear said. “Our commonwealth is fortunate to have him here teaching our future writers and now serving as our literary ambassador to the world.”

After Beshear — who is running for a second term ?— announced House’s appointment, the Republican Governors Association featured the writer in a 28-second attack ad calling him a “radical.”?

Among those who jumped to House’s defense on Twitter was singer Jason Isbell, who tweeted, “Silas is my friend and he’s a wonderful person and y’all can just stay mad.”?

I know that it's important especially for young queer people to see me in the public. ... I'm just happy to be out there as an openly gay person and to be visible and to show people that there is no monolithic gay person.

– Silas House

“Anybody who knows me knows how much I love Kentucky,” House said in response to the ad. “I, especially as poet laureate, seek to represent as many Kentuckians as I can. I think that my many different identities allows me to represent a whole lot of Kentuckians because I’m not just one thing. Nor is anybody else.”?

House wants people to think when they read his work, but said he doesn’t write with an agenda.?

He seeks to challenge people’s way of thinking — just like literature did for him.?

The reach of literature: Books can change a worldview?

House’s latest book, “Lark Ascending,” is full of warning signs about what can happen when people buy into extremism.?

“I know literature can get to people like that and can change people like that because it’s happened to me,” House said.?

When he was a child, he said, he mostly believed whatever he learned in church. But when he was 14, he read the frequently banned book, “The Color Purple” by Alice Walker.

“I had been raised with this idea of God as this old white man in the sky with a big long white beard and he’s watching everything and he’s ready to throw a lightning bolt at anybody who disobeys,” House explained. “And suddenly she is showing me this idea of God that is loving and wants people to be happy and wants people to have pleasure. … Part of me was resisting this, because I’m like, ‘that’s not the God I was taught about.’ And the other part of me is like, ‘this is the God that makes so much more sense to me.’”?

“The Color Purple” also exposed him to race and to people unlike him for the first time.?

“I was only raised around white people,” he said. “It wasn’t an integrated place.”?

Literature, he learned, can set in motion a thinking evolution and expanding point of view.?

“That book totally changed my way of thinking,” he said. “It changed my worldview so that I evolved in my thinking afterwards.”

One of the first works of literature House can remember reading was “Charlotte’s Web” by E. B. White. Much like his fascination with “The Waltons” on television, he saw parts of his family life represented on the page.? “It resonated with me because … my grandparents were farmers. And when I went to their house, there were hogs and chickens, and it was just like ‘Charlotte’s Web,’” he said. “And so I think reading ‘Charlotte’s Web’ was like, ‘wow, this is about people like us.’ It was about country people.”? (He’s also never been able to kill a spider since reading that book).? House also loved the television show “Little House on the Prairie” growing up, and because of that he read “The Long Winter” by Laura Ingalls Wilder early on.? The first book that “just destroyed me in all the best ways” was “The Outsiders: by S. E. Hinton.” He saw himself represented by the lead character Ponyboy.? “He’s an outsider because he’s so sensitive,” House said of that character. “He loves ‘Gone with the Wind’ and Robert Frost and looking at sunsets.” Silas House on the first books he can remember reading:?

Coal and climate change: ‘We have to transition.’?

In 2021 and 2022, House’s home region of Eastern Kentucky was hit with back-to-back deadly floods.?

Though the region has survived many such catastrophes, science predicts flooding will become worse as Kentucky’s climate warms because of climate-warming emissions built up in the atmosphere.?

House has often written about climate change, too, and advocated for protecting natural resources.?

“I hear a lot of politicians talking about ‘we need a transitional economy,’” he told the Lantern. “That’s their job – is to make that happen. And one way that that could really happen is through … being a part of solar and wind power creation.”?

Kentucky is missing an opportunity, he said, to lead when it comes to solving the climate crisis.?

“The whole state is just a ripe opportunity for that to happen in a widespread way and we’re not taking advantage of it,” he added. “I think it’s easy to see why we’re not because it doesn’t behoove some politicians as much as other forms of energy do.”?

House grew up in a coal and tobacco economy. His uncles, grandfather and brother-in-law worked in coal mines. His coal mining grandfather lost a leg in the mines, House said, and suffered from black lung, which is lung scarring from coal dust inhalation.?

“I just keep hearing ‘coal’ dragged out,” House said. “It’s a proud heritage. We fueled the world. And I’m really proud to be the grandson of a coal miner. That’s a big part of my identity. … But we have to move beyond that. We have to transition.”

Lawmakers need to be “more progressive in their thinking about a just transitional economy for Kentucky,” House said.?

He wishes climate change and natural resources discussions were not politicized.?

“It just blows my mind that things like … keeping our water clean is politicized,” he said. “There’s this whole idea that if you say, if you acknowledge that climate change is real, then … you’ve … exposed yourself as too liberal or something. It boggles my mind that … we don’t do everything in our power to protect our water and our resources. It just speaks of what an instant gratification way of thinking we have.”?

‘Poetry has really always sustained me.’?

Kentucky’s poet laureate, whose job is to elevate the literary arts in the state, need not be a poet.

House is known for his novels but he has published poetry. And the genre “has really always sustained me,” House said, comparing the form to music and song.?

“The first thing I do when I start working on a novel is: I gather the poetry that is going to speak thematically and tonally to the novel I’m working on,” House said.?

To him, the best poetry is accessible verse and “can speak to you pretty easily.”?

One of the poets he thinks does that well is Ada Limón, the United States poet laureate who makes a home in Lexington but is from Sonoma, California.?

“A lot of people are turned off by poetry that makes them feel dumb,” House said. “And her poetry is easy to read even while it’s incredibly profound, thought provoking.”?

Other notable writers of our time have called Kentucky home – bell hooks, Barbara Kingsolver, Wendell Berry and more.

House wants to use his tenure to bring more attention to Kentucky’s writing community — essentially marrying tourism with the literary tradition.?

“The state is wonderful (at) historical markers, but there’s not a lot of them about our literature,” he said. “So I want to figure out ways to better acknowledge our literary history and our legacy and make that more visible for people who are visiting.”?

He also wants to create a program that will teach Kentucky youth how to “take oral histories from their elders,” and produce them.?

“I have … a two-year window where I can do a lot of things to help, especially young writers,” House said.?

Already, House’s days are full. He teaches at Berea College and Spalding University’s Naslund-Mann Graduate School of Writing. He’s a freelancer and self-promoter on top of being a writer.?

As a creative, though, it’s important that he finds stillness to avoid burnout.?

He finds it by the creek in his yard or lying in the grass with his dog, Ari.?

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Kentucky libraries are seeing a surge in challenges to books, most having to do with sexuality and gender identity. (Getty Images)

Like libraries nationwide, Kentucky libraries experienced a surge in challenges to materials in 2022.

Data released by the American Library Association’s Office of Intellectual Freedom last week indicated the number of challenges nearly doubled in the U.S. since 2021, but in Kentucky they tripled. The number of attempts to restrict materials went from just seven to 22 and the number of titles challenged rose from 23 to 70.

Andrew Adler is president of the Kentucky Library Association, the state’s ALA chapter. He said most of the challenged titles have to do with LGBTQIA+ lifestyles or sexuality and that these challenges are motivated by “a culture of fear and misunderstanding.”

“As a librarian and someone who values anti-censorship and intellectual freedom, I am very appalled and concerned by what we’re seeing nationally. [People are] challenging these materials and the way in which they are being categorized and described … has been as ‘pornographic’ and ‘subversive,’ whenever they are definitely not,” Adler said. “The idea of trying to silence and limit voices that, for so long, have always had been oppressed historically, to try to continue to do that, and see those challenges continue is something that is concerning to me, and very disheartening.

“The way they’ve been categorized and attacked is something that I believe that all people should be concerned about, not just librarians, but the larger public as well.”

President Joe Biden also acknowledged the rising trend in attempted book bans earlier this week when he announced he was running for office again.

PEN America – a nonprofit tracking national book ban data – found more than 40% of the books challenged in the U.S. in 2022 had to do with LGBTQIA+ lifestyles or sexuality and 21% dealt with issues of race or racism.

There were nearly 1,300 demands to censor library books and resources in 2022 — nearly double the 2021 total. That’s the highest total of attempted book bans since ALA started compiling data more than 20 years ago.

Nearly 51% of the attempts to challenge or censor books took place in school libraries and schools and 48% of book challenges targeted materials in public libraries.

The most challenged book nationwide, and in Kentucky, in 2022 was Maia Kobabe’s graphic memoir “Gender Queer.”

Jen Gilbert is a school librarian in Henry County and the president of the Kentucky Association of School Librarians. Gilbert said some challenges have attempted to restrict as many as 25 books at a time.

“There’s definitely way more than have happened in previous years,” she said. “Probably what’s most unusual is just the ones that are happening in mass.”

That’s in line with what American Library Association president Lessa Kanani?opua Pelayo-Lozada said is happening across the U.S. She said in the past titles, were challenged when a parent or other community member saw a book in the library they didn’t like. But now, things are different: “Now we’re seeing organized attempts by groups to censor multiple titles throughout the country without actually having read many of these books.”

This represents a big shift in the past year. A 2022 poll commissioned by the ALA found “national bipartisan support for the freedom to read.” The data indicated that over 70% of U.S. voters are against efforts to remove books from public libraries, including 75% of Democrats, 70% of Republicans and 58% of Independents.

The wave of challenges in Kentucky last year preceded legislation passed by the state legislature this spring that lawmakers said would make challenging “obscene” material easier. It also comes a year after another bill passed into law granted local officials more power over who sits on the boards that govern libraries.

Senate Bill 5 – sponsored by Republican Sen. Jason Howell of Murray – mandated that school districts have a process in place when it comes to material challenges. It also defined what sort of material can be classified as “harmful to minors.” That bill passed into law without Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear’s signature in March.

Adler said all but two of Kentucky’s 171 school districts already had a policy in place and that the bill was “a solution in search of a problem.”

Howell told the Senate, “The great thing about this bill is it keeps us from deciding this up here as legislation,” in reference to the authority of school boards to review parents’ complaints. The far western Kentucky senator did not respond to requests for comment.

After the bill was delivered to Kentucky Secretary of State Michael Adams without Beshear’s signature, the Republican Party of Kentucky released a statementaccusing Beshear of taking “the coward’s way out” and not standing up for parental rights in education.

Gilbert said that challenges can be costly and time-consuming for library systems. Some have policies that include purchasing enough copies for every member of an evaluation committee to be able to read and discuss the work before making a ruling on the material in question.

“In general, you put a committee together, and you take a lot of time to consider that one work. When that suddenly balloons to that many titles, then that can’t continue to happen in the same way with the same fidelity,” Gilbert said. “It quickly becomes a question [of] how do you actually address those [challenges] then. In one county, they’re almost done with the first batch of 20 and another batch has already come in.”

Gilbert said she and her school librarian colleagues “want to protect kids all the time” and they’re willing to work with parents to offer alternatives to any required text they’re concerned about their children reading.

However, she doesn’t think libraries should outright ban materials that could be helpful for other students.

“There already have been processes and ways to talk that through and to work with parents and – when there’s a problem with a student and a concern – that can be addressed without removing the rights of an entire school’s worth of students,” Gilbert said. “I really feel like, what it’s landed us is [that] it’s easier to take things away now and that concerns me.”

What the future holds for challenges in Kentucky’s libraries is difficult for Adler to project, but he anticipates more of them.

“Each independent library system will have to make their own decisions as to how they’re going to face these challenges and face these movements against some of these titles,” he said. “What I suspect is that a number of them are going to go back and review their policies and see in what ways can they work to continue to protect the values that are important to the profession and to ensure that we are fulfilling our missions to provide information access and material access to all members of the commonwealth.”

This story is republished from WKMS, Murray State’s NPR station.

]]>Janis Ian grew up in New Jersey, a long way from the Kentucky knobs where an abolitionist minister founded Berea College in 1855. (Photo by Melissa Falen, courtesy of Janis Ian)

BEREA — On one of their visits, Janis Ian took Berea College President Lyle Roelofs to her studio. There he saw a photo of “a very young” Ian sitting at a grand piano. “Looking over her shoulder at the music she had written and was playing from,” he realized, was Leonard Bernstein, the legendary songwriter and longtime conductor of the New York Philharmonic.

Roelofs was visiting Ian to assure her that Berea would be a good home for her archives, which chronicle more than five decades of her work and life as a singer, songwriter, activist and winner of two Grammy Awards.

?The material in the collection, Roelofs said, “will just totally blow you away.”

For Ian, it’s a “win-win” because her vast personal collection has found a place where it will be not only safe and cared for but appreciated and used.?

As she and her wife, Pat Snyder, started looking for a home for the collection, Ian said they spoke with many major institutions and some “fairly substantial amounts of money” were thrown around.?

But many had so much in their collections that Ian’s things would spend most of their time in storage. For example, the Smithsonian Institution said it would be at least a decade before any of Ian’s material could be exhibited. Ian appreciated the frankness but also “realized that all of the major institutions would face the same problem.”

And then there was also the quirkiness of the collection, she said. “Who wants the archives of a songwriter, it’s not like that’s an important thing, right?”?

Ian’s friendships and correspondence embrace a wide range of people — Dolly Parton, Stella Adler, Willie Nelson, Mel Torme, Chick Corea, Lily Tomlin. There’s a book of poetry, her mother’s plays, a Grammy not only for best female pop performance (“At Seventeen” in 1975) but for best spoken word (“Society’s Child: My Autobiography” in? 2012), there’s her father’s — later her — guitar and the sheets where she composed her songs.

“Most archivists have been trained to deal in paper” Ian said, “and if it’s a Hollywood star like Katherine Hepburn, costumes, but not an artist like me.”

Ian grew up in New Jersey, a long way from the Kentucky knobs where an abolitionist minister founded Berea College in 1855. Her career took her to Los Angeles and around the world as a performer before she settled in Nashville.?

Berea never hit her radar until she and Snyder created the Pearl Foundation around 2000 to honor Ian’s mother, who had always dreamed of going to college but wasn’t able to until her successful daughter sent her. Through the foundation they wanted to help other people realize their dream of an education.?

She said her friend, songwriter Billy Edd Wheeler, told her “’look, if you’re going to be giving money away in scholarships you ought to be giving it to Berea,”’ where he had graduated in 1955. Plus, Snyder had a former student who had gone there and was “just raving about how great it was.”??

“We visited Berea once and we were as impressed as we expected to be,” she said, so they established an endowment to provide scholarships there but left it to the school to administer, remaining very hands-off.

Years later as they worked their way through the major institutions looking for a home for her archives they found, “there was always some reason that it wasn’t right.” And then they began to consider Berea again.?

For a small school Berea has a pretty significant archive that now includes the collections of author and activist bell hooks and Appalachian folk singer Jean Ritchie, “who I admire greatly,” Ian said.

Plus, there was Berea’s mission. It was the first integrated, co-educational college in the South and hasn’t charged tuition since 1892. “I really like the dichotomy,” Ian said. “Berea is not a Jewish school, not a particularly gay school, not a lot of the things that I am … and yet, it is.”

Like many Berea students, Ian said, “I started out on a farm. My earliest memories are of singing to the chickens from the back of a flatbed truck.” And her family worked hard to create a place for themselves in this world, like those of many Berea students. “My grandparents were immigrants, I always felt out of place, I’m self-educated, my dad was the first person in either family to graduate from college.” So, for all the differences, “there’s a lot of commonality.”

And then there was the fact that Berea invests in its students. Ian said Snyder summed it up: “All of these schools have $15 million stadiums and then there’s the school that has the $15 million students, which do you want to be aligned with?” In the end, “it was pretty much a no-brainer.”

Ian had lunch with Teresa Kash Davis, a Berea grad herself who is now the school’s vice president for alumni and philanthropy. After lunch, Ian recalled, she said, “so, why don’t I just leave Berea my archives, let’s just do that.” Davis “just kind of looked at me with her mouth hanging open and said ‘well, we can’t pay you.’” And that was fine.?

Roelofs and others made trips to Florida — where Ian and Snyder now live — to assure them the collection would get the attention it deserves. Over the course of 18 months they worked out details about how the material would be transferred, Berea’s financial commitment to the care and display of the collection and other arrangements, including Ian’s commitment to

helping raise money to support Berea’s work with the collection. “Janis is a very thoughtful person who makes sure she gets all the details right,” he said.

He sees that attention to detail in her work. The archives will offer Berea students who aspire to careers in music to see the “real discipline of songwriting,” Roelofs said. Every word in her songs, he said, has been “intentionally and carefully chosen.” It was an education for him. “I’m not a songwriter, I’m a theoretical physicist,” Roelofs said, but going through some of Ian’s papers has “deepened my appreciation of songwriting and the seriousness of that as an artistic pursuit.”?

For archivist Peter Morphew the lode of songbooks, diaries, family documents and personal memorabilia that Janis Ian has donated to Berea College can be summed up in one phrase: “It’s her life.”