An ultrasound machine sits next to an exam table in an examination room at a women’s health clinic in South Bend, Ind. A recent study shows that there was a spike in the number of women seeking sterilizations to prevent pregnancy in the months after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision striking down the constitutional right to an abortion. (Scott Olson/Getty Images)

In the months after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the constitutional right to an abortion, there was a spike in the number of women seeking sterilizations to prevent pregnancy, a recent study shows.

Researchers saw a 3% increase in tubal sterilizations per month between July and December 2022 in states with abortion bans, according to the study published in September in JAMA, a journal from the American Medical Association. The Supreme Court struck down Roe v. Wade in June 2022.

The study looked at the commercial health insurance claim records of 1.4 million people from 15 states with abortion bans (Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, Wisconsin and Wyoming). The study also examined the records of about 1.5 million people living in states with some abortion restrictions and 1.8 million in states where abortion remains legal. The researchers excluded 14 states that didn’t have records available for 2022.

“It’s probably an indication of women [who] wanted to reduce uncertainty and protect themselves,” said lead author Xiao Xu, an associate professor of reproductive sciences at Columbia University. In the first month after the ruling, sterilizations saw a one-time increase across all states included in the study, Xu and her team found. Her team also found continued increases in states that limited abortion to a certain gestational age, but those were not statistically significant.

The researchers compared records for three groups: States with a total or near-total ban on abortion, including states where bans were temporarily blocked; states where laws explicitly recognized abortion rights; and limited states, where abortion was legal up to a certain gestational age.

While the study captures only the early months following the Dobbs ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade, experts say it’s part of an increasing body of evidence that shows a growing urgency for sterilization procedures amid more limited access to abortions, reproductive health care and contraception. Other studies have shown increases in tubal sterilization (commonly known as “getting your tubes tied”) and vasectomy requests and procedures post-Dobbs.

Diana Greene Foster, a professor and research director in reproductive health at the University of California, San Francisco, said the results are not surprising, given the negative repercussions for women who seek to end their pregnancies but are not allowed to do so.

Foster led the landmark Turnaway Study, which for a decade followed women who received abortions and those who were denied abortions. It found that women forced to carry a pregnancy to term experienced financial hardship, health and delivery complications, and were more likely to raise the child alone.

“We have found that women are able to foresee the consequences of carrying an unwanted pregnancy to term,” Foster told Stateline. “The reasons people give for choosing an abortion — insufficient resources, poor relationships, the need to care for existing children — are the same negative outcomes we see when they cannot get an abortion.

“So it is not surprising that some people will respond to the lack of legal abortion by trying to avoid a pregnancy altogether.”

As abortion bans delay emergency medical care, this Georgia mother’s death was preventable

Few doctors and services

States with abortion bans and other restrictions also tend to have large swaths of maternal health care “deserts,” where there are too few OB-GYNs and labor and delivery facilities. That creates greater maternal health risks.

One such state is Georgia where abortion is banned after six weeks. Georgia’s abortion ban was temporarily lifted last week by a Fulton County judge, but on Monday the Georgia Supreme Court reinstated the ban. Dr. LeThenia “Joy” Baker, an OB-GYN in rural Georgia, said she sees patients in their early 20s who have multiple children and are seeking sterilizations to prevent further pregnancies, or who have conditions that make pregnancy dangerous for them. Her state has one of the highest maternal death rates in the nation.

On Monday, a Georgia county judge struck down the state’s six-week abortion ban, meaning that for now, women have access to the procedure up to about 22 weeks of pregnancy. The state is appealing the decision, and it’s expected to eventually be decided by the state Supreme Court.

The county judge’s ruling comes two weeks after ProPublica reported that two women in the state died after they couldn’t access legal in-state abortions and timely medical care for rare complications from abortion pills.

Black and Indigenous women disproportionately experience higher rates of complications, such as preeclampsia and hemorrhage, which contributes to their higher maternal mortality and morbidity rates. Baker said some of her patients say they want to avoid risking another pregnancy because of those previous complications.

“I have had quite a few patients, who were both pregnant and not pregnant, who inquire about sterilization,” she said. “I do think that patients are thinking a lot more about their reproductive life plan now, because there is very little margin.”

Along with the state’s abortion restrictions, Baker said women in her Bible Belt community feel social pressure that can push them toward sterilization.

‘Between rock, hard place:’ Will anyone ever have standing to challenge Kentucky’s abortion ban?

“It is definitely more socially acceptable to say, ‘I’m going to get my tubes tied or removed,’ than to say, ‘Hey, I want to find abortion care,’” Baker said.

In states where lawmakers have proposed restrictions on contraception, women might feel tubal sterilization to be the most surefire way to prevent pregnancy. Megan Kavanaugh, a contraception researcher at the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive health policy research center that supports abortion rights, said the research doesn’t say whether women who seek sterilization would have preferred another form of contraception.

“We need to both understand which methods people are using and whether those methods are actually the methods they want to be using,” said Kavanaugh, whose team studied contraceptive access and use in Arizona, Iowa, New Jersey and Wisconsin. “It’s really important to be monitoring both use and preferences in terms of heading towards an ideal where those are aligned.”

Tubal sterilizations can still fail at preventing a pregnancy, Foster said. One recent study noted that up to 5% of patients who underwent a tubal sterilization got pregnant later.

“If people are choosing sterilization who would otherwise pick something less permanent, then that is another very sad outcome of these abortion bans,” she added.

Another recent study, by Jacqueline Ellison, a University of Pittsburgh assistant professor who researches health policy, found that more young patients — both women and men — sought permanent contraceptive procedures in the wake of the Dobbs decision. The study focused on people ages 18 to 30 — the age group most likely to seek an abortion and the ones who previous studies suggest are most likely to experience “sterilization regret,” Ellison said.

A troubled history

The issue also can’t be disentangled from the nation’s history of coercive sterilizations, Ellison and other experts said. In the 1960s and 1970s, federally funded nonconsensual sterilization procedures were performed on Indigenous, Black and Hispanic women, as well as people with disabilities.

“People feeling pressured to undergo permanent contraception and people being forced into using permanent contraception are just two sides of the idea of reproductive oppression in this country,” Ellison said. “They’re just manifested in different ways.”

Medicaid, the joint federal-state health insurance program for low-income people, now has regulations designed to prevent coerced procedures. But the rules can have unintended consequences, said Dr. Sonya Borrero, an internal medicine physician and director of the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Innovative Research on Gender Health Equity.

The process includes a 30-day waiting period after a patient signs a sterilization procedure consent form, Borrero noted. But pregnant women who want the procedure done right after delivery might not reach the 30-day threshold if they go into early labor, she said. She added that some patients are confused by the form.

Borrero launched a tool called MyDecision/MiDecisión, an English and Spanish web-based tool that walks patients through their tubal ligation decision and dispels misinformation around the permanent procedure.

“The importance and the relevance of it right now is particularly pronounced,” she said.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

This article is republished from Stateline, a sister publication to the Kentucky Lantern and part of the nonprofit States Newsroom network.

]]>A young boy places a stone on the grave of his father as friends and family gather to commemorate the first anniversary of his death from heroin overdose. Between 2011 and 2021, more than 321,000 children across the U.S. lost a parent to a drug overdose, according to a recent federal study. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)

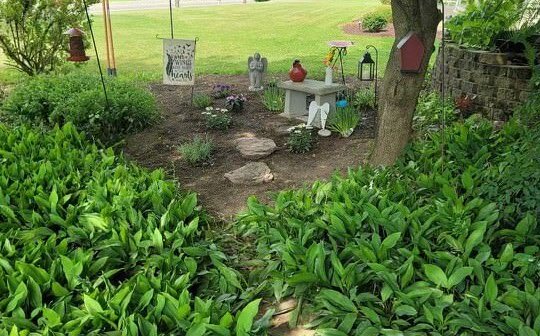

Every day, 8-year-old Emma sits in a small garden outside her grandmother’s home in Salem, Ohio, writing letters to her mom and sometimes singing songs her mother used to sing to her.

Emma’s mom, Danielle Stanley, died of an overdose last year. She was 34, and had struggled with addiction since she was a teenager, said Brenda “Nina” Hamilton, Danielle’s mother and Emma’s grandmother.

“We built a memorial for Emma so that she could visit her mom, and she’ll go out and talk to her, tell her about her day,” Hamilton said.

Lush with hibiscus and sunflowers, lavender and a plum tree, the space is a small oasis where she also can “cry and be angry,” Emma told Stateline.

Hundreds of thousands of other kids are in a similar situation: More than 321,000 children in the U.S. lost a parent to a drug overdose in the decade between 2011 and 2021, according to a study by federal health researchers that was published in JAMA Psychiatry in May.

In recent years, opioid manufacturers, distributors and retailers have paid states billions of dollars to settle lawsuits accusing them of contributing to the overdose epidemic. Some experts and advocates want states to use some of that money to help these children cope with the loss of their parents. Others want more support for caregivers, and special mental health programs to help the kids work through their long-term trauma — and to break a pattern of addiction that often cycles through generations.

The rate of children who lost parents to drug overdoses more than doubled during the decade included in the study, surging from 27 kids per 100,000 in 2011 to 63 per 100,000 in 2021.

Nearly three-quarters of the 649,599 adults between ages 18 and 64 who died during that period were white.

The children of American Indians and Alaska Natives lost a parent at a rate of 187 per 100,000, more than double the rate among the children of non-Hispanic white parents and Black parents (76.5 and 73.2 per 100,000, respectively). Children of young Black parents between ages 18 and 25 saw the greatest loss increase per year, according to the researchers, at a rate of almost 24%. The study did not include overdose victims who were homeless, incarcerated or living in institutions.

The data included deaths from illicit drugs, such as cocaine, heroin or hallucinogens; prescription opioids, including pain relievers; and stimulants, sedatives and tranquilizers. Danielle Stanley, Emma’s mother, had a combination of drugs in her system when she died.

At-risk children

Children need help to get through their immediate grief, but they also need longer-term support, said Chad Shearer, senior vice president for policy at the United Hospital Fund of New York and former deputy director at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s State Health Reform Assistance Network.

An estimated 2.2 million U.S. children were affected by the opioid epidemic in 2017, according to the hospital fund, meaning they were living with a parent with opioid use disorder, were in foster care because of a parent’s opioid use, or had a parent incarcerated due to opioids.

“This is a uniquely at-risk subpopulation of children, and they need kind of coordinated and ongoing services and support that takes into account: What does the remaining family actually look like, and what are the supports that those kids do or don’t have access to?” Shearer said.

Ron Browder, president of the Ohio Federation for Health Equity and Social Justice, an advocacy group, said “respecting the cultural traditions of families” is essential to supporting them effectively. The state has one of the 10 highest overdose death rates in the nation and the fifth-highest number of deaths, according to 2022 data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For second year in a row, Kentucky overdose deaths decrease?

The goal, Browder said, should be to keep kids in the care of a family member whenever possible.

“We just want to make sure children are not sitting somewhere in a strange room,” said Browder, the former chief for child and adult protection, adoption and kinship at the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services and executive director of the Children’s Defense Fund of Ohio.

“The child has gone through trauma from losing their parent to the overdose, and now you put them in a stranger’s home, and then you retraumatize them.”

This is a particular concern for Indigenous children, who have suffered disproportionate removal from their families and forced cultural assimilation over generations.

“What hits me and hurts my heart the most is that we have another generation of children that potentially are not going to be connected to their culture,” said Danica Love Brown, a behavioral health specialist and member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Brown is vice president of behavioral health transformation at Kauffman and Associates, a national tribal health consulting firm.

“We do know that culture is healing, and when people are connected to their culture … when they’re connected to their land and their community, they’re connected to their cultural activities, the healthier they are,” she said.

Ana Beltran, an attorney at Generations United, which supports kin caregivers and grandfamilies, said large families still often need money and counseling to take care of orphaned children. (UNICEF defines an orphan as a child who has lost at least one parent.) She noted that multigenerational households are common in Black, Latino and Indigenous families.

“It can look like they have a lot of support because they have these huge networks, and that’s such a powerful component of their culture and such a cultural strength. But on the other hand, service providers shouldn’t just walk away because, ‘Oh, they’re good,’” she said.

Counties with higher overdose death rates were more likely to have children with grandparents as the primary caregiver, according to a 2023 study from East Tennessee State University. This was particularly true for counties across states in the Appalachian region. Tennessee has the third-highest drug overdose death rate in the nation, following the District of Columbia and West Virginia.

‘Get well’

AmandaLynn Reese, chief program officer at Harm Reduction Ohio, a nonprofit that distributes kits of the opioid-overdose antidote naloxone, lost her parents to the drug epidemic and struggled with addiction herself.

Her mother died from an overdose 10 years ago, when Reese was in her mid-20s, and she lost her dad when she was 8. Her mom was a waitress and cleaned houses, and her dad was an autoworker. Both struggled with prescription opioids, specifically painkillers, as well as illicit drugs.

“Maybe we couldn’t save our mama, but, you know, somebody else’s mama is out there,” Reese said. “Children of loss are left out of the conversation. … This is bigger than the way we were seeing it, and it has long-lasting effects.”

In Ohio, Emma’s grandmother started a small shop called Nina’s Closet, where caregivers or those battling addiction can come by and collect clothing donations and naloxone.

Emma, who helps fill donation boxes, tells her grandmother she misses the scent of her mom’s hair. She couldn’t describe it, Hamilton said — just that “it had a special smell.”

And in an interview with Stateline, Emma said she wants kids like her to have hobbies — “something they really, really like to do” — to distract them from the sadness.

She likes to think of her mom as smiling, remembering how fun she was and how she liked to play pranks on Emma’s grandfather.

“This is what I would say to the users: ‘Get treatment, get well,’” Emma said.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: [email protected]. Follow Stateline on Facebook and X.

]]>A mother holds her baby. About 1 in 8 women suffer postpartum depression. With a new drug on the market approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the condition, experts and advocates are urging state Medicaid agencies and insurers to ensure equitable access to the treatment. John Moore/Getty Images

The first pill for postpartum depression approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is now available, but experts worry that?minority and low-income women, who are disproportionately affected by the condition, won’t have easy access to the new medication.

About 1 in 8 women experience symptoms of postpartum depression, federal data shows. Suicide and drug overdoses are among the leading causes of?pregnancy-related death, defined as death?during pregnancy, labor or?within the first year of childbirth. Black, Indigenous, Hispanic and low-income women are more likely to be affected.

Most antidepressants take six to eight weeks to take full effect. The new drug zuranolone, which patients take daily for two weeks, acts much faster. But the medication, manufactured jointly by Biogen and Sage Therapeutics under the brand name Zurzuvae, comes with a hefty price tag of nearly $16,000 for the two-week course.

Postpartum depression can be treated with a combination of therapy and other antidepressants. But Zurzuvae is only the second medication, and the first pill, that the FDA has approved specifically for the condition.

The first approved drug, brexanolone, also made by Sage Therapeutics, under the brand name Zulresso, costs $34,000 before insurance and requires a 60-hour hospital stay for an IV treatment. Doctors typically must get approval from patients’ health plans before prescribing it, and hospitals must be certified to administer it.

Experts and advocates are urging state Medicaid agencies to make sure the low-income patients who are covered under the joint state-federal program have easy access to Zurzuvae. They want Medicaid managed care plans — and private insurers — to waive any prior authorization requirements and other restrictions, such as “fail-first” approaches that require patients to try other drugs first.

Zurzuvae became available by prescription last month. Several state Medicaid agencies contacted by Stateline said they haven’t yet adopted a policy and will handle prescriptions on a case-by-case basis. Others said they automatically add FDA-approved drugs to their preferred drug lists, though some require prior authorization.

Medicaid covers about 41% of births nationwide and more than two-thirds of Black and Indigenous births, according to health policy research organization KFF.

As of last month, only 17 insurers in at least 14 states — less than 1% of the nation’s 1,000 private insurance companies — had published coverage guidelines for Zurzuvae, according to an analysis by the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health. Five of the 17 companies said they will require patients to try a different medication first. Three will mandate that psychiatrists prescribe Zurzuvae, though OB-GYNs can and do treat perinatal and postpartum depression, per the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Experts say restricting prescription privileges to psychiatrists will limit access because many of them don’t accept insurance. While most states now offer Medicaid coverage for a full year postpartum, many psychiatrists don’t accept Medicaid due to low reimbursement rates.

States also are grappling with shortages of psychiatrists and OB-GYNs.

“A lot of people in the early postpartum period are going to still be served by their obstetric provider, and if their obstetric provider is very, very far away, it’s going to be more difficult for them to get diagnosed with postpartum depression and have the recommended follow-up care, whether that’s through an obstetric provider or referral to a mental health care provider,” said Maria Steenland, a researcher on maternal and reproductive health services and health policy at Brown University.

Postpartum Medicaid expansion is the first step to maternal health equity, experts say?

In a statement to Stateline, a spokesperson for the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said Sage Therapeutics participates in the federal Medicaid drug rebate program, but that individual state Medicaid agencies will determine their own coverage policies.

Dr. Leena Mittall, a psychiatrist and chief of the Division of Women’s Mental Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, advocates a “no wrong door” approach to the new treatment and mental health coverage overall.

“I’m really hopeful that there will not be excessive restrictions in terms of especially burdensome authorization processes or availability,” she said. “If somebody’s seeking treatment or help, that we have multiple points of entry into care.”

In New Mexico, more than a third of residents are covered by Medicaid, the highest percentage in the nation, according to 2021 figures analyzed by KFF. New Mexico Medicaid said it automatically adds drugs approved by the FDA to its preferred drug list, meaning Zurzuvae is covered.

A spokesperson for the Medicaid agency in Louisiana, which has the nation’s second-highest proportion of Medicaid recipients at 32%, said it also will cover the drug.

In Illinois, where 20% of people are covered by Medicaid, officials told Stateline that for now, they will cover the cost of the medication on a case-by-case basis.

“We will not have them wait for our system to have it listed on that [preferred drug] roster,” said Dr. Arvind Goyal, chief medical officer of the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. “We will maybe talk to the prescriber and make sure that it’s the appropriate medication.”

The Massachusetts state health department told Stateline it will add Zurzuvae to its preferred drug list in March, but will require prescribers to get prior authorization. The Georgia Department of Community Health said it will consider coverage on a case-by-case basis until May 1, after the issue is discussed at an April drug board meeting.

“We recognize that Black and Brown women are reported to be disproportionally impacted by [postpartum depression]. In addition, those who live in rural areas and those who have Medicaid may be more likely to receive inadequate postpartum care, compared to those who live in urban areas,” Biogen spokesperson Allison Murphy wrote in the statement.

“We are also working with key stakeholders across states to help raise awareness of the importance of treating [postpartum depression] rapidly and helping remove potential barriers to treatment.”

In a 2022 report, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention detailed causes of maternal deaths between 2017 and 2019, finding that pregnant women and newly postpartum mothers were more likely to die from mental health-related issues, including suicides and drug overdoses, than any other cause. In total, mental health conditions were responsible for 23% of more than 1,000 maternal deaths, the CDC study found.

The Kentucky Lantern has previously reported that at least 8.4% of Kentucky’s maternal deaths between 2017 and 2019 were from suicide, according to a state report presented last February to the Senate Standing Committee on Health Services.

Mental health support needed to curb Kentucky’s maternal deaths

The CDC report also found that about 31% of maternal deaths among Indigenous women were due to mental health conditions. Black women, whose national maternal death rate is three times higher than white women’s, are twice as likely as white moms to suffer from a maternal mental health condition but half as likely to get treatment, according to the Maternal Mental Health Leadership Alliance.

Similarly, a review published in 2021 in The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing found a higher prevalence of postpartum depression among American Indian and Alaska Native women.

Previous analyses also have shown disparities in postpartum depression prevalence and its risk factors among Latina women.

Sage Therapeutics and Biogen tapped Kay Matthews, founder of Houston-based Shades of Blue, a national Black maternal mental health advocacy and support group, to help craft culturally sensitive advertising campaigns.

Matthews, who struggled with postpartum depression after giving birth to her stillborn daughter, said she was glad to see financial assistance programs offered but hopes they will continue beyond the rollout. Matthews said more pharmaceutical companies should focus on developing postpartum mental health drugs.

“We know that all drugs don’t work the same for everybody, right? There’s no one-size-fits-all approach,” she said. “The more we uplift these things in a way, then we start to really reach towards equitable care within a system that we know wasn’t designed to care for us, but we have the ability to change that.”

Catherine Monk, a clinical psychologist and director of the Perinatal Pathways Lab at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, said while the medication “isn’t a panacea,” access to it as a treatment option is an opportunity for insurers to improve mental health coverage parity.

“We’re stuck in our unfairness, and I’m deeply concerned about that,” Monk told Stateline. “Please cover it so we don’t have the situation of greater inequities in terms of access to frontline treatments. … [There’s] really strong evidence that these untreated mental health conditions contribute to maternal mortality.”

In Washington state, Uniform Medical, which covers state government employees, requires a diagnosis of severe postpartum depression, though Zurzuvae is approved for use by the FDA regardless of severity, according to the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health’s report.

University of Washington professor Dr. Ian Bennett, a family medicine physician, specializes in perinatal mental health. Bennett said he hopes that state Medicaid agencies won’t use the introduction of Zurzuvae as an excuse to cut back on other types of mental health care for new mothers. UnitedHealthcare Community Plan under Washington’s Apple Health, the state’s Medicaid program, added Zurzuvae to its preferred drug list but requires prior authorization.

“The issue is not just that we should be covering these medications, but that there needs to be an attention to the increasing costs of these medications and the need to increase overall coverage and funding of the cost for serving these communities,” he said.

In a recent MedPage Today piece, Monk and psychiatrist Dr. Andrew Drysdale criticized the new drug’s high cost, which they fear will limit access to the patients who need it most.

“We’ve already seen this play out with infused brexanolone: Barriers to treatment, such as cost, insurance coverage, availability, and logistical difficulties, have hampered uptake,” she and Drysdale wrote.

Stateline, like Kentucky Lantern, is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: [email protected]. Follow Stateline on Facebook and Twitter.

]]>A man jogs past a sign about crisis counseling on the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. The Biden administration is pushing insurers and state regulators to improve mental health care coverage. (Eric Risberg/The Associated Press)

If you or someone you know is in need of help, dial 988 for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline for free and confidential support or text?HELLO?to 741741 for the Crisis Text Line.

When she tried to find help for her daughter’s depression, Michelle Romero was frantic, panicked and heartbroken. She searched and searched for mental health clinicians within her daughter’s insurance coverage network.

But the Houston-area mom of three couldn’t find a psychiatrist nor a psychotherapist who accepted her daughter’s health insurance and was close enough to the family’s neighborhood, she said. In her network, one clinician had closed their practice. Another was at capacity with patients.

So, each week, the family paid?about?$300 out of pocket for their daughter’s psychotherapy and psychiatry sessions. Romero has maxed out her credit cards.

At Christmastime last year, Romero’s daughter was hospitalized for two weeks. Then 14, she had tried to kill herself. It wasn’t her first attempt: That was when she was a 10-year-old fifth grader.

The?family began the new year with a $30,000 hospital bill, of which insurance paid just a portion.

The Biden administration is pushing insurers and state regulators to improve mental health care coverage. The move comes as overdose deaths rise and youth mental health problems grow more rampant, disproportionately affecting communities of color. Inflation and a shortage of mental health care providers, including psychiatrists and specialists who treat adolescents, further hinder access to care.

“Something needs to change,” Romero said. “There are too many people who need help. And there’s not enough doctors.” Insurers, she said, “need to do better.”

The federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, enacted in 2008, doesn’t require insurance plans to offer mental health coverage — but if they do, the benefits must be equal with coverage for other health conditions. That means deductibles, copayments, out-of-pocket limits and prior authorizations — approvals from health plans for a particular service or to fill a prescription — can’t be more stringent than those for other medical care.

But despite the federal law, many insurers continue to charge higher copayments for mental health care, limit the frequency of mental health treatment, or impose more restrictive prior authorization policies, according to The Kennedy Forum, a nonprofit that advocates for equal mental health coverage. A joint report provided this year to Congress by the Department of Labor, the Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of the Treasury validated those assertions.

The Biden administration recently proposed a rule that would strengthen parity under the law by requiring that insurers show how their coverage rules affect patients by, for example, sharing denial rates for mental health care claims compared with other claims. The insurers also would have to provide data on other restrictions, such as prior authorization. The public comment period just ended.

The new rule also would close a loophole that has allowed more than 200 state and local government health insurance plans to opt out of the law.

The whole thing about parity is realizing that mental health and physical health are the same.

– Kim Jones, executive director of Georgia’s National Alliance on Mental Illness chapter

Since the parity law was enacted 15 years ago, “nobody can claim that we’ve achieved parity,” said Shawn Coughlin, president and CEO of the National Association for Behavioral Healthcare, a nonprofit that represents mental health care providers, programs and facilities. Coughlin said the problem is prevalent across the board — from private insurance plans to Medicaid managed care.

To provide greater oversight, some states have passed their own parity policies. Over the past decade, 10 states have fined insurance companies a total of nearly $31 million for violating parity rules, according to The Kennedy Forum. And since 2018, 17 states have passed legislation requiring insurers to demonstrate compliance on an annual basis, according to the Council of State Governments.

“We’ve been playing this rope-a-dope with them [insurers] now for 15 years. And the fact is that without more stringent enforcement, plans have just basically scoffed at the law and have ignored the law,” Coughlin said. “This is why states have stepped in … because the federal parity law really just does not have any real teeth in this enforcement.”

In most states, patients with private insurance have to go out-of-network for behavioral health care more often than they do for other health care, reports The Kennedy Forum. Narrower networks are a notorious problem for mental health care, compounded by clinician shortages. In Texas, where Romero lives, about 98% of the state’s counties are at least partially designated as mental health professional shortage areas.

In a collaborative with other groups, including Health Law Advocates and the Treatment Research Institute, the nonprofit created a state parity policy tracker and compiled a list of resources to help patients find their state regulators to submit a parity violation claim.

Shortages and dismal reimbursement rates

When her daughter’s asthma flares up, Maria Garcia has no problem getting her insurance to cover a visit to the pediatrician.

But when her sixth grade girl began to suffer severe anxiety — sobbing daily, cutting off her hair and trying to hurt herself — she couldn’t find a psychologist that accepted their insurance and took new patients. The ones who did had a six-month wait time.

Garcia and her husband had to pay out of pocket — around $200 per therapy session each week on top of home-schooling expenses. Garcia had to pull her daughter out of school last year because of her severe anxiety.

“I was desperate. I felt really powerless,” Garcia said in Spanish through an interpreter. “My daughter was saying she wanted to kill herself.”

After months of searching, Garcia found Community Does It, a nonprofit that offers free, culturally competent therapy sessions for immigrant families.

But other nonprofits haven’t been able to remain in operation. Last month, Phoenix House Texas, a drug rehabilitation program for low-income Texas youth, closed its doors, citing unsustainable reimbursement rates.

Because insurers typically reimburse mental health care providers at lower rates than other providers, psychiatrists are less likely to participate in insurance plans, studies show. This forces patients to pay out of pocket, or, if their coverage includes mental health care, file an insurance claim to get partial reimbursement, assuming they’ve met their annual deductible.

“Psychiatrists are actually paid a lot more to deliver services out-of-network than they are to deliver service in-network, which is a clear, natural disincentive to participating in insurance or accepting insurance,” said Dr. Jane Zhu, a primary care physician and professor at Oregon Health & Science University’s Center for Health Systems Effectiveness. “There is a lot of evidence that suggests that these low participation rates amongst psychiatrists in particular are driven in part by low reimbursement.”

Zhu, who researches mental health parity and access to care, noted about 27 states and Washington, D.C., have reported increases in or plans to increase Medicaid reimbursement rates for behavioral health services between 2022 and this year. But in many states, the rate change is minimal.

States parity statutes vary

The American Psychiatric Association created model parity legislation tailored to each of the 50 states and Washington, D.C., with a focus on insurer and state regulator accountability.

Right now, parity policies vary widely, but?some?states have been making strides?toward tightening their rules. Georgia, which?the research and advocacy nonprofit Mental Health America ranks 47th?in provider availability at?640 residents?per mental health provider, last year?began requiring?health insurers to use “generally accepted” health care standards when reviewing claims, instead of their own non-scientific criteria. Sometimes, insurance plans will deny coverage, claiming the care isn’t medically necessary.

“The whole thing about parity is realizing that mental health and physical health are the same,” said Kim Jones, executive director of Georgia’s National Alliance on Mental Illness chapter.

Like Romero and Garcia, Jones couldn’t find an in-network clinician for her own 9-year-old son, who suffered panic attacks. He was on a three-month wait list for a psychologist, an hour away and out-of-network.

Meanwhile, statutory language in other states, such as Florida, poses more hurdles.

The state — 46th in access to care, according to Mental Health America’s report — requires insurance plans to offer “optional coverage” for mental health conditions.

“The insurance company or the employer can offer or choose to offer it as part of their package. It doesn’t mandate it,” explained Marni Stahlman, president and CEO of the Mental Health Association of Central Florida. “That’s where we see the loophole.”

What’s more, the statute says a plan can limit outpatient mental health treatment to a maximum of $1,000.

“If benefits are provided beyond the $1,000 per benefit year, the durational limits, dollar amounts, and coinsurance factors thereof need not be the same as applicable to physical illness generally,” the Florida statute reads.

Cherlette McCullough, an Orlando, Florida-based mental health counselor who recently began accepting insurance, said one client’s plan only covers five sessions of psychotherapy.

“It’s extremely limited,” McCullough said. “There can be one traumatic incident where treatment needs about 13 sessions to work through it. So, what happens after she completes those five sessions?”

It would be “unheard of,” Stahlman of the Mental Health Association of Central Florida said,?if a breast cancer patient “was told that she could have three sessions of chemotherapy.”

Back in Texas, many therapy sessions later, Romero’s daughter is better and recovering.

Months ago, Romero had emptied out the medicine cabinet for fear of her daughter using pills.

In their place, Romero left a message.

She?cut a heart out of pale yellow construction paper and pasted it inside?for her daughter. On it she wrote the words:

“You are worth it. You are loved.”

This story is republished from Stateline, a sister publication to the Kentucky Lantern and part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: [email protected]. Follow Stateline on Facebook and Twitter.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.