Voters in Grand Rapids, Mich., cast their ballots during the state’s August primary. Michigan was one of the swing states that has greatly expanded voter access since 2020. (Matt Vasilogambros/Stateline)

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. — Some voters are already casting early ballots in the first presidential election since the global pandemic ended and former President Donald Trump refused to accept his defeat.

This year’s presidential election won’t be decided by a margin of millions of votes, but likely by thousands in the seven tightly contested states of Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

How legislatures, courts and election boards?have reshaped?ballot access in those states in the past four years could make a difference. Some of those states, especially Michigan, cemented the temporary pandemic-era measures that allowed for more mail-in and early voting. But other battleground states have passed laws that may keep some registered voters from casting ballots.

Trump and his allies have continued to spread lies about the 2020 results, claiming without evidence that widespread voter fraud stole the election from him. That has spurred many Republican lawmakers in states such as Arizona, Georgia and North Carolina to reel back access to early and mail-in voting and add new identification requirements to vote. And in Pennsylvania, statewide appellate courts are toggling between rulings.

“The last four years have been a long, strange trip,” said Hannah Fried, co-founder and executive director of All Voting is Local, a multistate voting rights organization.

“Rollbacks were almost to an instance tied to the ‘big lie,’” she added, referring to Trump’s election conspiracy theories. “And there have been many, many positive reforms for voters in the last few years that have gone beyond what we saw in the COVID era.”

The volume of election-related legislation and?court cases?that emerged over the past four years has been staggering.

Nationally, the Voting Rights Lab, a nonpartisan group that researches election law changes,?tracked 6,450 bills?across the country that were introduced since 2021 that sought to alter the voting process. Hundreds of those bills were enacted.

Justin Levitt, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, cautioned that incremental tweaks to election law — especially last-minute changes made by the courts — not only confuse voters, but also put a strain on local election officials who must comply with changes to statute as they prepare for another highly scrutinized voting process.

“Any voter that is affected unnecessarily is too many in my book,” he said.

New restrictions

In many ways, the 2020 presidential election is still being litigated four years later.

Swing states have been the focus of legal challenges and new laws spun from a false narrative that questioned election integrity. The 2021 state legislative sessions, many begun in the days following the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, brought myriad legislative changes that have made it more difficult to vote and altered how ballots are counted and rejected.

The highest profile measure over the past four years came out of Georgia.

){var e=document.querySelectorAll("iframe");for(var t in a.data["datawrapper-height"])for(var r=0;rUnder a 2021 law, Georgia residents now have less time to ask for mail-in ballots and must put their driver’s license or state ID information on those requests. The number of drop boxes has been limited. And neither election officials nor nonprofits may send unsolicited mail-in ballot applications to voters.

Republican Gov. Brian Kemp said when signing the measure that it would ensure free and fair elections in the state, but voting rights groups lambasted the law as voter suppression.

That law also gave Georgia’s State Election Board more authority to interfere in the makeup of local election boards. The?state board[AS1]??has made recent headlines?for paving the way for counties to potentially refuse to certify the upcoming election. This comes on top of?a wave?of voter registration challenges from conservative activists.

In North Carolina, the Republican-led legislature last year?overrode?Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper’s veto to enact measures that shortened the time to turn in mail-in ballots; required local election officials to reject ballots if voters who register to vote on Election Day do not later verify their home address; and required identification to vote by mail.

This will also be the first general election that North Carolinians will have to comply with a 2018 voter ID measure that was caught up in the court system until the state Supreme Court?reinstated?the law last year.

And in Arizona, the Republican-led legislature pushed?through?a measure[AS2]??that shortened the time voters have to correct missing or mismatched signatures on their absentee ballot envelopes. Then-Gov. Doug Ducey, a Republican, signed the measure.

“Look, sometimes the complexity is the point,” said Fried, of All Voting is Local. “If you are passing a law that makes it this complicated for somebody to vote or to register to vote, what’s your endgame here? What are you trying to do?”

Laws avoided major overhauls

But the restrictions could have gone much further.

That’s partly because Democratic governors, such as Arizona’s Katie Hobbs, who took office in 2023,?have vetoed?many of the Republican-backed bills. But it’s also because of how popular early voting methods have become.

Arizonans, for example, have been able to vote by mail for more than three decades. More than 75% of Arizonan voters?requested?mail-in ballots in 2022, and 90% of voters in 2020 cast their ballots by mail.

This year,?a bill?that would have scrapped no-excuse absentee voting passed the state House but failed to clear a Republican-controlled Senate committee.

Bridget Augustine, a high school English teacher in Glendale, Arizona, and a registered independent, has been a consistent early voter since 2020. She said the first time she voted in Arizona was by absentee ballot while she was a college student in New Jersey, and she has no concerns “whatsoever” about the safety of early voting in Arizona.

“I just feel like so much of this rhetoric was drummed up as a way to make it easier to lie about the election and undermine people’s confidence,” she said.

Vanessa Jiminez, the security manager for a Phoenix high school district, a registered independent and an early voter, said she is confident in the safety of her ballot.

“I track my ballot every step of the way,” she said.

Ben Ginsberg, a longtime Republican election lawyer and Volker Distinguished Visiting Fellow at the think tank Hoover Institution, said that while these laws may add new hurdles, he doesn’t expect them to change vote totals.

“The bottom line is I don’t think that the final result in any election is going to be impacted by a law that’s been passed,” he said on a recent call with reporters organized by the Knight Foundation, a Miami-based nonprofit that provides grants to support democracy and journalism.

Major expansions

No state has seen a bigger expansion to ballot access over the past four years than Michigan.

Republicans tried to curtail access to absentee voting,?introducing 39 bills?in 2021, when the party still was in charge of both legislative chambers.

Two?GOP?bills?passed, but Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer vetoed them.

The next year, Michigan voters approved ballot measures that added nine days of early voting. The measures also allowed voters to request mail-in ballots online; created a permanent vote-by-mail list; provided prepaid postage on absentee ballot applications and ballots; increased ballot drop boxes; and allowed voters to correct missing or mismatched signatures on mail-in ballot envelopes.

“When you take it to the people and actually ask them about it, it turns out most people want more voting access,” said Melinda Billingsley, communications manager for Voters Not Politicians, a Lansing, Michigan-based voting rights advocacy group.

“The ballot access expansions happened in spite of an anti-democratic, Republican-led push to restrict ballot access,” she said.

In 2021, then-Nevada Gov. Steve Sisolak, a Democrat,?signed into law?a measure that transitioned the state into a universal vote-by-mail system. Every registered voter would be sent a ballot in the mail before an election, unless they opt out. The bill made permanent a temporary expansion of mail-in voting that the state put in place during the pandemic.

Nevada voters?have embraced?the system, data shows.

In February’s presidential preference primary, 78% of ballots cast were ballots by mail or in a ballot drop box, according to the Nevada secretary of state’s office. In June’s nonpresidential primary, 65% of ballots were mail-in ballots. And in the 2022 general election, 51% of ballots cast were mail ballots.

Last-minute court decisions

Drop boxes weren’t controversial in Wisconsin until Trump became fixated on them as an avenue for alleged voter fraud, said Jeff Mandell, general counsel and co-founder of Law Forward, a Madison-based nonprofit legal organization.

For half of a century, Wisconsinites could return their absentee ballots in the same drop boxes that counties and municipalities used for water bills and property taxes, he said. But when the pandemic hit and local election officials expected higher volumes of absentee ballots, they installed larger boxes.

After Trump lost the state by fewer than 21,000 votes in 2020, drop boxes became a flashpoint. Republican leaders claimed drop boxes were not secure, and that nefarious people could tamper with the ballots. In 2022, the Wisconsin Supreme Court, then led by a conservative majority,?banned?drop boxes.

But that ruling would only last two years. In July, the new liberal majority in the state’s high court?reversed the ruling?and said localities could determine whether to use drop boxes. It was a victory for voters, Mandell said.

With U.S. Postal Service delays stemming from the agency’s restructuring, drop boxes provide a faster method of returning a ballot without having to worry about it showing up late, he said. Ballots must get in by 8 p.m. on Election Day. The boxes are especially convenient for rural voters, who may have a clerk’s office or post office with shorter hours, he added.

“Every way that you make it easy for people to vote safely and securely is good,” Mandell said.

After the high court’s ruling, local officials had to make a swift decision about whether to reinstall drop boxes.

Milwaukee city employees were quickly dispatched throughout the city to remove the leather bags that covered the drop boxes for two years, cleaned them all and repaired several, said Paulina Gutierrez, executive director of the City of Milwaukee Election Commission.

“There’s an all-hands-on-deck mentality here at the city,” she said, adding that there are cameras pointed at each drop box.

Although it used a drop box in 2020, Marinette, a community on the western shore of Green Bay, opted not to use them for the August primary and asked voters to hand the ballots to clerk staff. Lana Bero, the city clerk, said the city may revisit that decision before November.

New Berlin Clerk Rubina Medina said her community, a city of about 40,000 on the outskirts of Milwaukee, had some security concerns about potentially tampering or destruction of ballots within drop boxes, and therefore decided not to use the boxes this year.

Dane County Clerk Scott McDonell, who serves the state capital of Madison and its surrounding area, has been encouraging local clerks in his county to have a camera on their drop boxes and save the videos in case residents have fraud concerns.

A risk of confusing voters

Many local election officials in Wisconsin say they worry that court decisions, made mere months before the November election, could create?confusion?for voters and more work for clerks.

“These decisions are last-second, over and over again,” McDonell said. “You’re killing us when you do that.”

Arizonans and Pennsylvanians now know that late-in-the-game scramble too.

In August, the U.S. Supreme Court?reinstated?part of a 2022 Arizona law that requires documented proof of citizenship to register on state forms, potentially?impacting?tens of thousands of voters, disproportionately affecting young and?Native?voters.

Whether Pennsylvania election officials should count mail ballots returned with errors has been a subject of litigation in every election since 2020. State courts continue to?grapple?with the question, and neither voting rights groups nor national Republicans show signs of giving up.

Former Pennsylvania Secretary of the Commonwealth Kathy Boockvar, who is now president of Athena Strategies and working on voting rights and election security issues across the country, said voters simply need to ignore the noise of litigation and closely follow the instructions with their mail ballots.

“Litigation is confusing,” Boockvar said. “The legislature won’t fix it by legislation. Voter education is the key thing here, and the instructions on the envelopes need to be as clear and simple as possible.”

To avoid confusion, voters can make a plan for how and when they will vote by going to?vote.gov, a federally run site where voters can check to make sure they are properly registered and to answer questions in more than a dozen languages about methods for casting a ballot.

Arizona Mirror’s Caitlin Sievers and Jim Small, Nevada Current’s April Corbin Girnus and Pennsylvania Capital-Star’s Peter Hall contributed reporting.

]]>An election observer monitors two poll workers processing absentee ballots in the Milwaukee Election Commission warehouse on Aug. 13. Discrepancies in the count could be used by county canvassing boards in swing states as a reason not to certify elections. (Photo by Matt Vasilogambros/Stateline)

GRAYLING, Mich. — Clairene Jorella was furious.

In the northern stretches of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula, the Crawford County Board of Canvassers had just opened its meeting to certify the August primary when Jorella, 83 years old and one of two Democrats on the panel, laid into her Republican counterparts.

Glaring, she said she was gobsmacked by the partisan opinions they’d recently aired publicly.

“We are an impartial board,” she told them a day after the primary election, sitting at a conference room table in the back of the county clerk’s office. “We are expected to be impartial. We are not expected to bring our political beliefs into this board.”

The two Republicans, Brett Krouse and Bryce Metcalfe, had two weeks earlier written a letter to the editor of the local newspaper, endorsing a candidate for township clerk because of “her commitment to election integrity.”

Citing their positions on the Board of Canvassers, the letter went on to claim that because of new state election laws, including one that allows for early voting, “All of the ingredients required for voter fraud were present.”

Jorella thought the letter was inappropriate. And she had reason to worry, having seen in recent years Republican members of county boards in Michigan and in other states refuse to certify elections when their preferred candidate lost. It was a preview of the battles communities nationwide might face in November’s presidential election.

Metcalfe, 48, said he didn’t do anything wrong.

“I don’t serve the Democrat Party in any way, shape or form,” he said. “I serve the Republican Party.”

“Bryce, you serve the people,” said Brian Chace, 77, the board’s other Democratic member.

Metcalfe raised his voice. “I will not be silenced.”

The board members argued for 20 minutes, then broke into two bipartisan teams to begin their task at hand. In a process known as canvassing, they looked through documents precinct by precinct, making sure that the total votes shown on a polling place’s ballot tabulator matched the number of ballots issued.

While members of the board eventually certified the election after meeting a few times over the following week, the kerfuffle illustrates the tension consuming communities around the country over one of the crucial final steps in elections.

Stateline crisscrossed Michigan and Wisconsin — two states critical in the race for the presidency — to interview dozens of voters, local election officials and activists to understand how the voting, tabulation and certification processes could be disrupted in November.

There is broad concern that, despite checks and balances built into the voting system, Republican members of state and county boards tasked with certifying elections will be driven by conspiracy theories and refuse to fulfill their roles if former President Donald Trump loses again.

Last month, the Georgia State Election Board passed new rules that would allow county canvassing boards to conduct their own investigations before certifying election results. State and national Democrats have sued the state board over the rules.

The fear that these efforts could sow chaos and delay results is not unfounded: Over the past four years, county officials in the swing states of Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada and Pennsylvania have refused to certify certain elections. After immense pressure, county officials either changed their minds, or courts or state officials had to step in.

“People are now trying to interfere with this otherwise pretty boring process, based on the false idea that the 2020 presidential election was stolen, and that widespread voter fraud continues to pervade our election system,” said Lauren Miller Karalunas, a counsel for the Brennan Center, a voting rights group housed at the New York University School of Law.

“This is a mandatory process with no room for these certifying officials to go behind the results to investigate anything,” she added.

What they do

Clerks: Municipal or county clerks are tasked with running elections, along with other duties including issuing marriage licenses, collecting fines and maintaining death records. They supervise the election workers who manage and prepare for an upcoming election, as well as the poll workers on duty for Election Day.

Canvassers/certifiers: A board of canvassers is a bipartisan panel of Democrats and Republicans that ensures the accuracy of precinct or ward vote total numbers. The boards also certify the elections. There is broad concern this year that Republican members of some state and county boards will refuse to fulfill their roles if former President Donald Trump loses again.

‘We’re working for the people’

Michael Siegrist, the Democratic clerk for Canton Township, Michigan, has zero patience for election deniers.

On the Saturday before the August primary, he stood before 11 soon-to-be poll workers at a training session, repeatedly emphasizing one point: Run a good, clean, legal election.

“All of the rules we have in place are either to protect the integrity of the election or to protect the voters,” Siegrist said. The trainees nodded along.

Down the hall, two dozen election inspectors and township officials opened and processed absentee ballots.

“We’re working for the people,” Siegrist continued. “We’re not working for ourselves. We’re not working for our philosophies. And we’re not working for our political parties.”

Siegrist, who serves a suburban Detroit community of nearly 99,000 people within Wayne County, has seen it before.

Two Republican members of the Wayne County Board of Canvassers initially refused to certify more than 800,000 votes cast during the 2020 presidential election; Siegrist was one of many people who joined a Zoom call the county board set up for public comments two weeks after the election and berated them.

“We are basically doing what no foreign country has ever been able to do, which is successfully undermine our election system,” he told them.

Years later, the Detroit News uncovered audio of Trump pressuring those GOP members of the Wayne County Board of Canvassers not to certify the 2020 election, promising them legal representation. Siegrist is still concerned about the certification process and worries that board members will be compromised by partisanship and refuse to certify the election in November.

In 2021, Robert Boyd, at the time the newest Republican on the Wayne County Board of Canvassers and one of the people who will be tasked with certifying November’s election, told the Detroit Free Press that if he were in his position in 2020 he would not have certified the election.

Certifying elections had been a mostly routine formality for more than a century across the country. The results that come out after the polls close on election night are unofficial and need to be certified. While laws vary slightly by state, bipartisan, citizen-led panels are typically tasked with certifying elections at both the county and state levels.

Usually known as boards of canvassers, the panel’s job is to compare the number of ballots cast according to poll books with the number of ballots fed through a tabulator. Sometimes, those numbers don’t match.

Those mismatches are to be expected and are almost always handled swiftly. But in 2020, they formed one of the bases for the lie — spread widely by Trump and his supporters — that the election was stolen in favor of Democrat Joe Biden.

If the numbers are off in a precinct — usually by one or two votes — a poll worker might provide an explanation to the canvassing board. A voter may have been impatient with a long line and left the precinct with a ballot in hand, for example, or two ballots may have been stuck together. Sometimes, board members ask poll workers or municipal clerks to come in and explain a discrepancy.

It’s a tedious process akin to watching paint dry, said Christina Schlitt, president of the League of Women Voters of Grand Traverse Area, which sends volunteers throughout Michigan to make sure canvassing board members follow the rules.

“They’re not to look for any nefarious actions, although some inexperienced canvassers, particularly in one party, seem to look for problems,” she said, referring to the GOP.

The proper way to contest the election results is not through the certification process, she said. Aggrieved candidates can always call for a recount or go to the courts.

Local officials prepare

Barb Byrum, the Democratic clerk for Ingham County, Michigan, recently had to use some of her political capital to keep an election denier off the certifying panel for the county of nearly 285,000 people.

Republican members of the county’s Board of Commissioners listened to and agreed with Byrum, an outspoken former state representative who is not afraid to negotiate.

“I needed someone else,” she said, praising cooperative local leaders. “Many other county clerks did not have that luxury, so they do have conspiracy pushers and believers on their board of canvassers.”

Byrum, whose county includes the state capital of Lansing, works from the county courthouse in Mason, a rural city of about 8,200 people. “Hometown, U.S.A.” signs line its streets. Downtown, LGBTQ+ flags hang from the windows of Byrum’s first-floor office, where passersby can see them through the beech trees.

After Trump lost Michigan in 2020, his supporters sued to have Ingham County’s and two other counties’ 1.2 million votes excluded from the state’s 5.5 million vote count, saying there had been “issues and irregularities.” At the time, Byrum called the lawsuit “ludicrous” and full of conspiracy theories. Biden won the state by 154,000 votes.

The desire to keep election troublemakers off county canvassing boards is bipartisan.

Justin Roebuck, the clerk for Ottawa County, Michigan, and a Republican, said he has been dispelling election lies about alleged widespread fraud in elections since 2016. So, he feels more prepared than ever to deal with potential disruptions this fall.

“It’s not something that I worry about; it’s something that I prepare for,” said Roebuck, who serves a county of about 301,000 people who live near Lake Michigan’s coastline.

“We’re asking our community to trust us,” he added. “I want to trust them too. I want to be able to dialogue with people, even in heated situations.”

During the 2022 midterm elections, a group of around 15 voters went to the Board of Canvassers meeting and said there must be fraud because the Republican gubernatorial candidate had received fewer voters than the county commissioner in a precinct. They accosted Roebuck in the hallway, he recalled.

Instead of getting security involved, he invited them into a nearby conference room.

“We have to be transparent and talk through the challenges,” he said.

A preview of November

One of the leading voices questioning the integrity of Wisconsin’s elections is named Jefferson Davis.

On the morning of Wisconsin’s Aug. 13 primary, Davis quarterbacked the Republican observers at the Milwaukee Election Commission’s warehouse south of downtown. The only person wearing a suit in a sea of casually dressed election workers, Davis weaved throughout the crowded facility with familiarity.

“I don’t care if you beat me in an election, as long as you don’t cheat or steal or compromise or whatever,” he told Stateline, before outlining eight ways he claimed voter fraud is occuring in Wisconsin, including inflated voter lists, noncitizens voting and harvesting ballots from people in long-term care facilities.

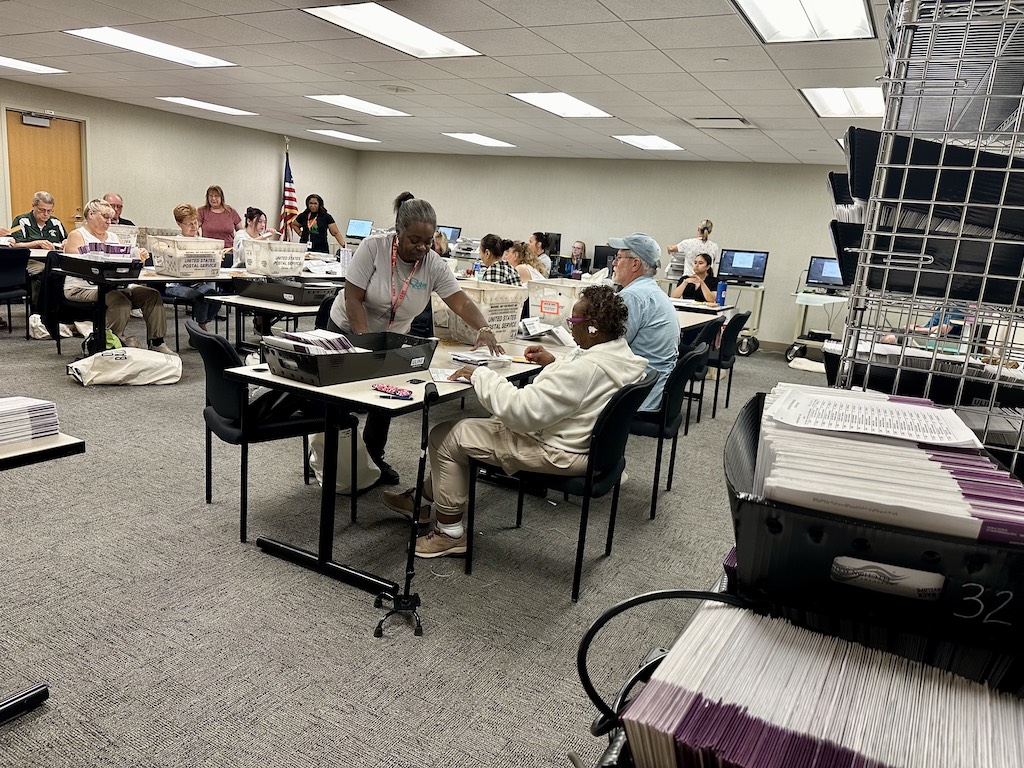

Davis, the spokesperson for a group called the Ad-hoc Committee for the Wisconsin Full Forensic Physical and Cyber Audit, placed his people in front of the yellow caution tape that sectioned off election workers who were processing 23,000 absentee ballots. There were 15 Republican observers and two Democrats and a handful of unaffiliated observers.

Bipartisan pairs of Democratic, Republican or unaffiliated poll workers sorted and counted absentee ballots, checking to see whether the voter had provided their required signature and address on the envelope. The workers wore paper wristbands colored blue, red or purple to mark their party affiliation. Facing hours of work, some brought pillows for their chairs.

Davis’ observers had clipboards and forms, developed by the Republican National Committee, noting the number of security cameras, tables, election workers by political affiliation, building access points and tabulating machines. They also noted when and why each ballot was rejected.

“We care about our Constitution, we care about our freedom, our liberty, our independence, because we cannot have an election stolen again,” Davis said, raising his voice over the whirr of four high-speed letter openers.

Before the ballot-counting process began, Brenda Wood, a member of the Board of Absentee Canvassers in Milwaukee, walked observers through the rules: They had to stay three feet away from election workers and could only ask them a voter’s name and address and why an absentee ballot was rejected.

“If they provide only ‘Milwaukee, Wisconsin,’ and not their street address, then it will be rejected,” Wood said.

“Oh good,” Davis quickly responded.

After her spiel, Davis rapidly but politely peppered her with more than 20 questions that he called “quickies,” grilling her on the day’s process. He wanted to make sure there wasn’t any “hanky-panky” going on. Other observers asked one or two questions.

Throughout the day, election workers processed ballots without significant issues. Occasionally, one would raise a cardboard paddle to ask staff a question about procedure or whether they should reject a ballot. At one point, an election worker, overwhelmed by observers asking her questions, put her forehead on the table and asked them to give her space.

“Can we put a note saying the observer wanted this ballot rejected?” asked one GOP observer, wanting to have her concern in writing on the ward’s official documents.

“You can, but we’re not going to reject it,” a commission staffer said. “It’s the rules. It’s how we’ve been doing it.”

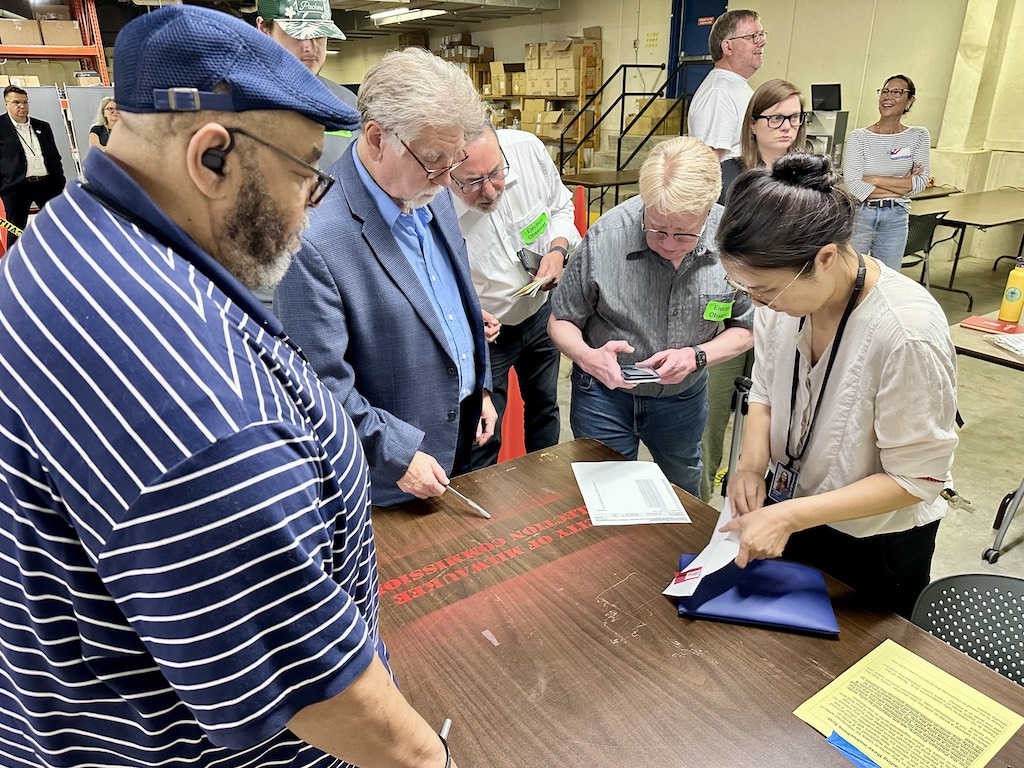

Fourteen hours later, around 9 p.m. and after all the absentee ballots had been counted, Bonnie Chang, another member of the Board of Absentee Canvassers, went around with blank flash drives and downloaded the vote totals from the nine ballot tabulators in the warehouse.

A gaggle of observers followed her every step, while the chairman of the Republican Party of Milwaukee County, a member of the Wisconsin Election Commission who was one of Trump’s fake electors in 2020 and a host of others looked on.

As two county election workers who had been paired that day were leaving the warehouse, one leaned over to the other.

“It’ll be busy in November,” she said.

“We’ll make it through,” he said.

“We always do,” she responded.

This story is republished from Stateline, a sister publication to the Kentucky Lantern and part of the nonprofit States Newsroom network.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Poll workers check in a voter during Georgia’s May primary at a Marietta polling place. Local election officials across the country face a poll worker shortage, and a coalition of election leaders, nonprofits and businesses are making a push for more on Aug. 1, National Poll Worker Recruitment Day. (Matt Vasilogambros/Stateline)

This week, a coalition of election officials, businesses, and civic engagement, religious and veterans groups will make a national push to encourage hundreds of thousands of?Americans to serve as poll workers in November’s presidential election.

Poll worker demand is high. With concerns over the harassment and threats election officials face, and with the traditional bench of poll workers growing older, hundreds of counties around the country are in desperate need of people who are willing to serve their communities.

On Aug. 1, there will be a social media blitz across Facebook, TikTok, X and other platforms that will encourage Americans to spend a few hours helping democracy. They’re being asked to wake up before sunrise, welcome voters to polling places, hand them a ballot, and make sure the voting process goes smoothly.

Many sites will see long lines and frustrated voters; they may face unexpected problems such as a power outage or a cantankerous voting machine. Nearly all will hand out scores of tiny “I Voted” stickers.

Poll workers are the face of our democracy and the face of our elections.

– Marta Hanson, national program manager for the nonpartisan Power the Polls

The U.S. Election Assistance Commission, a federal agency that works with election officials to improve the voting process, established the recruitment day in 2020. The commission offers a social media toolkit, full of suggested hashtags and cartoon video snippets, to help local election officials reach potential new workers. There are 100,000 or so polling places across the country, and the agency’s website shows potential workers how to sign up.

“Serving as a poll worker is the single most impactful, nonpartisan way that any individual person can engage in the elections this year,” said Marta Hanson, the national program manager for Power the Polls, one of the leading nonpartisan groups in the recruitment effort.

“Poll workers are the face of our democracy and the face of our elections,” she told Stateline.

Launched in the spring of 2020 during the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic, Power the Polls gathered nonprofits and businesses together to help election workers close the gap left after many poll workers, who tend to be older, decided to no longer serve due to health concerns. Nearly half of the poll workers who served in 2020 were older than 60.

The group’s effort recruited 700,000 prospective poll workers nationwide.

“It is our vision that every voter has someone who looks like them and speaks their language when they show up at the polling place, and that election administrators have the people that they need,” Hanson said.

Polling places still need poll workers. This year Power the Polls is tracking more than 1,835 jurisdictions, spanning all 50 states and the District of Columbia, that the group identified through outreach to election administrators, monitoring local news and working with on-the-ground partners.

Of those jurisdictions, Hanson said, 700 towns and counties have “really, really high needs.”

For example, Boston needs 500 new poll workers by its Sept. 3 primary, while Detroit needs 1,000 more people to sign up before November. In small towns in Connecticut and rural California, officials are desperate to find 20 people to help. Los Angeles County is looking for people who speak one of a dozen languages that are prevalent in the area.

In suburban Cobb County just outside of Atlanta, Director of Elections Tate Fall said recruiting poll workers has been difficult, but not at the level she’s heard about in other communities nationally. Her team has found success at farmers markets, Juneteenth festivals and senior services events.

Among her challenges, she said, is that many of the poll workers who have signed up this year are new and need more training and practice before November. She also worries about reliability.

“It’s just we have a lot of people sign up and then they never mark their availability, or they only want to work in their precinct,” Fall said. “We need people that are a bit more flexible. But overall, we’re doing good.”

Over the past four years, local election officials have been bombarded by misinformation, harassment and threats fueled by the lie that the 2020 presidential election was stolen.

To ease voters’ skepticism about ballot security, officials will often welcome them into the elections office and give them a tour.

In Nevada, Carson City Clerk-Recorder?Scott Hoen goes a step further by inviting skeptical residents to see the election process firsthand as a poll worker.

“Lo and behold, once they go through the cycle, they understand and they can touch, feel it, see it, know it, understand it, that we run a really good, tight election here in Carson City,” Hoen said. “I think they have a better comfort with me now doing that, teaching them what’s going on.”

In Marion County, Florida, Supervisor of Elections Wesley Wilcox has been worried about people who believe the 2020 election was stolen working as poll workers and potentially disrupting the voting process. But the required training to become a poll worker has alleviated some of that concern.

“We’ve had them, and they actually become some of our advocates in this process,” he said.

Joseph Kirk, the election supervisor for Bartow County, Georgia, said that, beyond learning about the voting system, being a poll worker is just fun.

Kirk tells voters that it’s an opportunity to take a day off work, get paid, meet new people, see the characters of the community and enjoy a good meal, since some poll workers bring in homemade food to share.

And for the high school government students he recruits in their classes, it’s a way to participate in elections as early as 16.

“It’s a community,” he said. “And being part of it is really special.”

Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: [email protected]. Follow Stateline on Facebook and X.

]]>Voters line up outside a Takoma Park, Maryland, polling place. Takoma Park is one of 17 jurisdictions nationally that allow noncitizens to vote in local elections. (Jose Luis Magana/The Associated Press)

Preventing people who are not United States citizens from casting a ballot has reemerged as a focal point in the ongoing Republican drive to safeguard “election integrity,” even though noncitizens are rarely involved in voter fraud.

Ahead of November’s presidential election, congressional and state Republican lawmakers are aiming to keep noncitizens away from the polls. They’re using state constitutional amendments and new laws that require citizenship verification to vote. Noncitizens can vote in a handful of local elections in several states, but already are not allowed to vote in statewide or federal elections.

Some Republicans argue that preventing noncitizens from casting ballots — long a boogeyman in conservative politics — reduces the risk of fraud and increases confidence in American democracy. But even some on the right think these efforts are going too far, as they churn up anti-immigration sentiment and unsupported fears of widespread fraud, all to boost turnout among the GOP base.

While Republican congressional leaders want to require documentation proving U.S. citizenship when registering to vote in federal elections, voters in at least four states will decide on ballot measures in November that would amend their state constitutions to clarify that only U.S. citizens can vote in state and local elections.

Over the past six years, Alabama, Colorado, Florida, Louisiana, North Dakota and Ohio have all amended their state constitutions.

In Kentucky — which along with Idaho, Iowa and Wisconsin is now considering a constitutional amendment — noncitizens voting will not be tolerated, said Republican state Sen. Damon Thayer, who voted in February to put the amendment on November’s ballot. Five Democrats between the two chambers backed the Republican-authored legislation, while 16 others dissented.

“There is a lot of concern here about the Biden administration’s open border policies,” Thayer, the majority floor leader, told Stateline. “People see it on the news every day, with groups of illegals pouring through the border. And they’re combined with concerns on election integrity.”

U.S. House Speaker Mike Johnson expressed similar concerns last month when he announced new legislation — despite an existing 1996 ban — that would make it illegal for noncitizens to vote in federal elections. During a trip to Florida to meet with former President Donald Trump, the Louisiana Republican said it’s common sense to require proof of citizenship.

“It could, if there are enough votes, affect the presidential election,” he said, standing in front of Trump in the presumptive presidential nominee’s Mar-a-Lago resort. “We cannot wait for widespread fraud to occur, especially when the threat of fraud is growing with every single illegal immigrant that crosses that border.”

That rhetoric is rooted in a fear about how the U.S. is changing demographically, becoming more diverse as the non-white population increases, said longtime Republican strategist Mike Madrid. Though this political strategy has worked to galvanize support among GOP voters in the past, he questions whether this will be effective politically in the long term.

“There’s no problem being solved here,” said Madrid, whose forthcoming book, “The Latino Century,” outlines the group’s growing voter participation. “This is all politics. It’s all about stoking fears and angering the base.”

Noncitizens are voting in some elections around the country, but not in a way that many might think.

Where noncitizens vote

In 16 cities and towns in California, Maryland and Vermont (along with the District of Columbia), noncitizens are allowed to vote in some local elections, such as for school board or city council. Voters in Santa Ana, California, will decide in November whether to allow noncitizens to vote in citywide elections.

In 2022, New York’s State Supreme Court struck down New York City’s 2021 ordinance that allowed noncitizens to vote in local elections, ruling it violated the state constitution. Proponents have argued that people, regardless of citizenship status, should be able to vote on local issues affecting their children and community.

During the first 150 years of the U.S., 40 states at various times permitted noncitizens to vote in elections. That came to a halt in the 1920s when nativism ramped up and states began making voting a privilege for only U.S. citizens.

The number of noncitizen voters has been relatively small, and those voters are never allowed to participate in statewide or national elections. Local election officials maintain separate voter lists to keep noncitizens out of statewide databases.

In Vermont’s local elections in March, 62 noncitizens voted in Burlington, 13 voted in Montpelier and 11 voted in Winooski, all accounting for a fraction of the total votes.

In Takoma Park, Maryland, of the 347 noncitizens who were registered to vote in 2017, just 72 cast a ballot, according to the latest data provided by the city. And in San Francisco, 36 noncitizens registered to vote in 2020 and 31 voted.

This is all politics. It’s all about stoking fears and angering the base.

– Mike Madrid, Republican strategist and author

Voter turnout among noncitizens is low for two reasons, said Ron Hayduk, a professor of political science at San Francisco State University, who is one of the leading scholars in this area. Many noncitizens in these jurisdictions do not realize they have the right to vote, and many are afraid of deportation or legal issues, he said.

Registration forms in jurisdictions that allow noncitizens to vote in local elections do acknowledge the risks. In San Francisco, local election officials warn that the federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement or other agencies could gain access to the city’s registration lists and advise residents to consult an immigration attorney before registering to vote.

“Immigrants were very excited about this new right to vote, they wanted to vote, but many of them did not ultimately register and vote because they were concerned,” Hayduk said.

While there are some noncitizens participating in a handful of local elections, they’re not participating illegally in any substantial way in state and national elections.

Though there’s room for legitimate debate about whether noncitizens should be allowed to vote at the local level, there is no widespread voter fraud among noncitizens nationally, said Walter Olson, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank.

In 2020, federal investigators charged 19 noncitizens for voting in North Carolina elections. A national database run by The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, shows that there have been fewer than 100 cases of voter fraud tied to noncitizens since 2002, according to a recent count by The Washington Post.

Trump continues to falsely assert that he was the rightful winner of the 2020 presidential election and that he had more of the popular vote in 2016. He has claimed without evidence that voter fraud was to blame, including in part from noncitizens.

With illegal immigration near the top of major issues for voters ahead of November, Trump and his movement sense they have momentum with the public to tie immigration concerns with their continued election claims, Olson said.

It’s a way of keeping Democrats on the back foot, by falsely accusing them of allowing immigrants to come into the country illegally so they can vote, he added.

“The imaginings that there is some sort of plot by an entire major political party is just remarkably evidence-free,” he said.

Fighting ‘the left’

Although voter fraud among noncitizens is not happening widely, states should still add protections to their voting systems to prevent that possibility, said Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a Republican.

Kentucky Republicans and Democrats prepare to face off on ‘school choice’ amendment

Raffensperger has been a major proponent of a Peach State law that requires documentation to verify the citizenship status of voters. In 2022, he announced that an internal audit of Georgia’s voter rolls over the past 25 years found that 1,634 noncitizens had attempted to register to vote, but not a single one cast a ballot.

“I will continue to fight the left on this issue so that only American citizens decide American elections,” Raffensperger wrote in a statement to Stateline.

Meanwhile, lawmakers in Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina and West Virginia are actively considering legislation that would add ballot initiatives for November to prevent noncitizen voting. Those bills are at various points in the legislative process, with many having already passed one chamber.

During a committee hearing last week, Republican Missouri state Sen. Ben Brown said the state’s constitutional language is vague enough to allow cities to let noncitizens vote. While presenting his bill, he cited California’s parallel constitutional wording and how cities such as Oakland and San Francisco allow noncitizens to vote in local elections.

Most state constitutions have similar language around voter eligibility, saying that “every” U.S. citizen that is 18 or over can vote. The proposed amendments usually would change one word, emphasizing that “only” U.S. citizens can vote, eliminating an ambiguity in the text that has left room for cities in several states to allow noncitizen participation in elections.

It’s a “pretty simple” fix, said Jack Tomczak, vice president of outreach for Americans for Citizen Voting, a group that works with state lawmakers to amend their constitutions so that only citizens can vote in state and local elections.

“It does dilute the voice of citizens of this country,” Tomczak said. “And it also dilutes the nature of citizenship.”

This story is republished from Stateline, a sister publication to the Kentucky Lantern and part of the nonprofit States Newsroom network.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Along a highway just south of Fox, Ore., ranch owners post their support for the movement to join Idaho. If Eastern Oregon succeeds in joining Idaho, it could breathe life into similar secessionist movements nationwide. (Photo by Matt Vasilogambros/Stateline)

ENTERPRISE, Oregon — This small ranching town, surrounded by towering tree-topped mountains and a valley of rolling grass fields, sits tucked into the northeast corner of the state — both out of the way and right in the middle of a contentious debate.

At a meeting late last month, 25 people packed into a stuffy conference room in the Wallowa County Courthouse — 35 miles west of the Idaho state line and 260 miles east of Portland — to hear county commissioners debate a single agenda item: leaving Oregon.

The Greater Idaho movement, which wants to secede from the Beaver State and become a part of its neighbor to the east, had sputtered along for years, gaining little traction. But then, the coronavirus hit in the spring of 2020.

The global pandemic was “a blessing” for the movement, according to Mike McCarter, who took up the movement’s mantle in 2019. Quarantines and remote learning inflamed residents’ anger with the state government for shutting down schools and businesses. This tension invigorated the effort to join Idaho, a state whose government reacted wholly differently to COVID-19 than Oregon did.

“Our movement brings things to light, and it brings hope,” McCarter said. “I don’t want to see the guns picked up. I don’t want to see the battles. Why can’t we sit down and talk?”

Secession is a long shot that would require approval by Congress; so far, there have been ballot measures, and there has been a lot of talk. But the fact that the movement has gotten even this far illustrates the growing tear in the American fabric.

Greater Idaho has seen a success that other secessionist movements, regionally and in states such as California and Illinois, never reached. If supporters here achieve their goal, it could mean a paradigm shift nationally, proponents say, inspiring more states to split along cultural and political lines.

County by county, Eastern Oregonians have voted on similar measures over the past three years, securing much of the large rural region for the secessionist movement. In June, Wallowa County became the 12th to pass a ballot initiative in support of joining Idaho. The measure, to begin biannual discussions, won by just seven votes of the 3,497 that were cast.

In the stone courthouse last month, in a town square that honors the first settlers who came in the 1880s and the Nez Perce peoples who predated them, supporters argued that Democratic lawmakers, who control the capitol in Salem and were elected largely by Western Oregonians, have ignored the other side of the state and are hurting its way of life.

“I just feel unrepresented, completely,” said Rob DeSpain, standing tall in the back of the room, his white goatee pronounced under a black cap. “We just don’t have a voice. It’s very frustrating.”

Shaking his head at a series of pro-secession speakers who brought up transgender youth, urban decay and the struggle to protect cattle from wolves, another man, David Hayslip, finally raised his hand. There would be cuts in the minimum wage, he pointed out to his neighbors, and a new state sales tax and a potential decline in home values if they joined Idaho.

“If you want to go over there, U-Haul has really good deals,” Hayslip said after exhaling in frustration, looking up from the floor. “Don’t like it here? Hit the road. This is democracy, folks. You don’t like the results? You keep fighting in the democratic system.”

Other residents opposed to secession said they feared what would happen if they lost access to abortion rights, health care coverage, infrastructure funding, mail-in voting and marijuana. Some of them said that while they weren’t born in Oregon, they have lived in the state more years than not. They’re Oregonians and want to remain Oregonians.

The room was split, much like the county. But as in other small towns in America, people knew one another, greeting old friends and neighbors before tension filled the room.

Oregon is divided geographically, politically, economically and culturally. Beyond the Cascades, the population drops off with the elevation, as the terrain turns from the moist mountains of the coast and the fertile farmland and progressive population hubs of the Willamette Valley to the high desert, golden grasslands and craggy mountain ranges of the immense east.

Stateline traveled more than 1,000 miles of Eastern Oregon, where supporters of the movement to join Idaho said they feel unheard by the decisionmakers in Salem. Would-be secessionists freely recognize that their communities represent less than a tenth of the state’s population, but they also asked: Don’t we matter?

“You have two very different cultures that shouldn’t be sharing a state government,” said Matt McCaw, the spokesperson for the Greater Idaho movement and a resident of Powell Butte, an unincorporated town near the geographic center of Oregon.

Their grievances are many: They dislike rules that restrict tree-cutting, protect coyotes and promote electric vehicles. They oppose transgender rights, classroom discussions of gender and race, and limits on guns. They detest the taxes and regulations they believe have devastated the region’s economy. And they hate what became of Portland, a city many of them look back on with nostalgia.

For many Eastern Oregonians, there’s a sense of desperation, as if all options have been exhausted and all that remains is joining Idaho.

“I have people come at me and say, ‘Well, what can we do to change it?’” said McCarter, a deeply religious man and an Air Force veteran. “It’s gone too far over the top to change. It really has. It is a battle for our freedom and our self-sufficiency.”

Whether they can succeed is another story.

While they work to secure more wins at the ballot box — including in Crook County next May, and later Gilliam and Umatilla counties — supporters of the movement are beginning a broader effort to lobby the Idaho and Oregon legislatures to start an interstate dialogue to shift their border — a dialogue for which Oregon Democrats do not have an appetite.

A growing movement out of a divided state

Sitting on the front deck of his single-story green home in La Pine, a wooded city of 2,500 people who live past the lava fields south of tourism haven Bend, McCarter has two flags flying off his house: the American flag and the Idaho flag.

When the 76-year-old is not assisting with pastoral duties at his 30-person church, he fills his retired life with fixing old ham radios, getting back into long-distance running, teaching gun safety and leading the Greater Idaho movement.

Though McCarter lives in Deschutes County — which voted for President Joe Biden in 2020 with 53% support and has not voted to join Idaho — Oregon’s new border could follow the Deschutes River, he said, snaking to the west of his home and putting him within the new Idaho boundary.

I just feel unrepresented, completely. We just don’t have a voice. It’s very frustrating.

– Ron DeSpain, an Eastern Oregon. resident who supports joining Idaho

Greater Idaho could encompass roughly 15 eastern counties, representing 65% of Oregon’s landmass and one congressional district. Each county handily voted for former President Donald Trump in 2020 with two-thirds or more of the vote. While the movement tried ballot initiatives in Douglas and Josephine counties, which are west of the Cascade Range, those failed in 2022.

A splintering of Oregon would mean new tax structures, a transfer of public debts, the loss of state parks and natural resources, and a fundamental shift in social program benefits. The details could take years to work out, but that’s a problem down the line, supporters say. Now, they just want the two states to start talking about a transition.

Supporters for the movement vote mostly Republican, but some are socially conservative while others are more economically libertarian. Some are not even registered to a political party.

“I have very deep roots in the state, or what used to be this state,” said Sandie Gilson, a fifth-generation Oregonian with ancestors who mined gold and operated sawmills. “I don’t recognize it.”

Over chicken Caesar salad at a Main Street eatery in John Day, a town in a high-desert canyon, Gilson described how she’s crisscrossed Grant County, even planning to speak at an upcoming Democratic Party meeting, to talk about the deterioration of Portland, how taxes and regulations stifle housing, and the unrealistic shift away from gas-powered cars for rural communities.

The policies of Salem don’t consider the commonsense requirements of life in the state’s east, she said.

Don’t like it here? Hit the road. This is democracy, folks. You don’t like the results? You keep fighting in the democratic system.

– David Hayslip, an opponent of secession

Oregon hasn’t had a Republican governor since 1987; Democrats have held a trifecta for more than a decade, controlling the governor’s office as well as the state House and Senate.

This is one of the latest iterations of a debate over minority political representation that is as old as this nation’s founding, Gilson said. The U.S. Constitution was written to encourage consensus, she said; the Revolutionary War was fought because people were being taxed but not listened to. “Isn’t that our message?” she asked.

Stephen Piggott doesn’t see it that way.

“I totally understand their concerns,” said Piggott, the momentum program director for Western States Strategies, a Portland-based nonpartisan social welfare organization that campaigned against the ballot measure in Wallowa County. “But for Greater Idaho, there’s no other solution except to say, ‘We can’t find any common ground, so screw it, we’re?going to just go up and leave.’”

And while it may not be espousing racist viewpoints, the movement is supported by white nationalists and militia leaders such as Ammon Bundy, Piggott said, harking back to Oregon’s racist founding, when Black people were banned from settling the land. Among the 15 counties that could be part of Greater Idaho, all but three have white populations above 75%, according to census numbers.

Greater Idaho proponents vehemently reject charges of racism or hatred, saying they can’t control the people who agree with their cause. And they say they are not seeking violence, but a peaceful political solution.

“I have people come to me and say, ‘But isn’t this movement kind of racist?’ Well, I had nothing to do with that,” McCarter said, the air around his home still thick with wildfire smoke. “In rural Oregon, if it’s predominantly white, so be it. And we make a point that we don’t get into that angle at all. That’s not what it’s about.”

Retired chimney sweep Grant Darrow said that letting a few counties join Idaho could be a “pressure relief valve” to avoid violence from people long frustrated with Oregon’s policies.

“People are fighting mad,” said Darrow, who sported a handlebar mustache and an “Awake Not Woke” T-shirt in his home in Cove, Oregon, a town nestled in an agricultural valley. “If you’re not moving in a direction that everybody thinks positive, it’s going to blow up.”

But to slice up states to reflect residents’ politics is not how the American political system works, regardless of an urban-rural divide that exists across the country, said Judy Stiegler, a former Oregon Democratic state representative who now is a political science instructor at Oregon State University-Cascades, located in Bend.

“We should be having conversations with each other,” Stiegler said. “The Greater Idaho movement is taking advantage of people’s frustrations. And I believe they’re not being honest about the real objective, which is power.”

The reality of the secession happening is “slim to none,” she said. She expects neither state Democrats nor Congress to endorse the move.

Can it pass the Idaho and Oregon legislatures?

When Idaho Republican state Rep. Barbara Ehardt first heard about Oregon’s movement to join her state, it just resonated with her. Why wouldn’t Idaho be interested in more land, more resources such as timber, minerals and water, and more like-minded people? she asked.

“You can only push people so far, demanding that they acquiesce to some of your non-constitutional whims before people push back,” Ehardt said.

In February, the Idaho House passed her bill to open a formal interstate dialogue with Oregon to secure those counties that want to secede. Although it didn’t move forward in the Senate, Ehardt is “hopeful and optimistic” she can get her bill passed in both the legislative bodies next year. For this to succeed, “it will involve the hand of the Lord.”

When the Oregon state legislature reconvenes next year, Republican state Sen. Dennis Linthicum plans on reintroducing legislation to let those 15 eastern counties secede and join Idaho. His bill died in committee earlier this year.

“I thought we were talking about tolerance and welcoming all ideas and welcoming other thoughts and perspectives, and it turns out none of that is true,” said Linthicum, who voted for the Klamath County ballot measure. “It’s a storyline. And that’s why Eastern Oregonians are fed up with it.”

While she “1,000% agrees” with the reasons why people are so frustrated with the policies coming out of Salem, freshman Republican state Rep. Emily McIntire worries about Eastern Oregonians who have superior health care, child care, food stamps and other state services than Idaho offers, including Oregon’s $14.20 minimum hourly wage compared with Idaho’s $7.25, the federal minimum wage.

“Everybody that’s working at a Walmart in a county in Eastern Oregon, that Walmart can go, ‘We’re going to drop you guys all down to eight bucks an hour,’” she said. “It’s not just like we flip the switch, you’re part of Idaho and everything stays as it is.”

In Enterprise, the meeting wrapped up after more than an hour of discussion involving those in the room and another 30 people who joined by Zoom. The county commissioners finally chimed in.

Though they are officially neutral on the question, all three said they understood the concerns expressed by both sides. Commissioner John Hillock said he’s submitted pieces of legislation, grant proposals for sewer and water projects and new funding requests for the county fairgrounds to lawmakers in Salem and been ignored. He gets it.

As does Commissioner Susan Roberts, who asked attendees to come up with ideas before they meet next in February on how to constructively move forward and get “our friends on the west side of the state” to have a dialogue.

“They don’t get us. On the other hand, I don’t get most of them. Most of the time, I can’t figure it out,” she said with a chuckle. “But that is the back-and-forth that we need.”

Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: [email protected]. Follow Stateline on Facebook and Twitter.

]]>Crime in Kentucky was down in 2022 compared with the previous year. (Photo by Brandon Bell, Getty Images)

When shots ring out on the South and West sides of Chicago, Sam Castro and his team at the Institute for Nonviolence Chicago race to the scene of the shooting and to the hospital where emergency responders are treating the gunshot victim.

Knowing most of the city’s gun violence is caused by a small cluster of people who are usually gang-affiliated, the group wants to prevent the often-expected retaliation shooting by intervening in victims’ lives to stop the cycle of violence and the revolving doors of the hospital.

Castro, the organization’s director of community violence intervention, and his colleagues meet gunshot victims at their hospital beds and walk the streets of the Austin, Back of the Yards, Brighton Park and West Garfield Park neighborhoods, talking with those who are at a high risk of committing or being the victim of gun violence. They offer individualized “wraparound” support services, whether being a caseworker, delivering food or helping residents find and keep jobs.

Like many of the people who run these programs nationally, Castro has personal experience with gun violence. He’s been shot three times, the first when he was 3.

“We’re investing in the people in communities that have been disinvested for generations.”

– William Simpson, Equal Justice USA

He became part of the gun violence cycle as a gang leader, spending 12 years in state and federal prison. He wanted something better for his children and community through “relentless engagement.” It’s his calling, he said.

“It’s hard,” Castro told Stateline. “We’ve been through some traumatic stuff. We’ve got to figure out how to heal the people in the community while still running into this gunfire.”

Now the Institute for Nonviolence Chicago and similar organizations nationwide have a new opportunity to expand their work. A massive injection of federal grant money, beyond the private philanthropy that has previously sustained their mission, will help more programs offer an alternative to law enforcement that, supporters say, gets at the root drivers of violence.

“We’re investing in the people in communities that have been disinvested for generations,” said William Simpson, the director of violence reduction initiatives at Equal Justice USA, a nonprofit that advocates for public funding for these programs in states like California, Louisiana, New Jersey and North Carolina.

“Folks are doing the lifesaving work and never getting the resources they need to do it,” Simpson said. “The dollars are allocated, but there’s so much more work.”

He and Castro were among roughly 700 experts from 200 organizations in 45 cities who gathered last week at a community violence intervention conference in Los Angeles, hosted by the Giffords Center for Violence Intervention. The program launched last year within the national gun safety organization led by former U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords of Arizona, a mass shooting survivor.

Part pep talk, part professional development seminar, the conference gave people from some of the deadliest and economically depressed cities in the country a chance to share their strategies for curbing urban gun violence, tapping new funding streams and getting more state and city money.

Feds invest big

Through its Community Violence Intervention and Prevention Initiative, the Biden administration recently freed up $50 million in grants for community violence intervention programs. This comes on top of the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, which President Joe Biden signed last year, allocating $250 million over the next five years for these programs.

This is the largest federal investment in community violence intervention programs in U.S. history, said Amy Solomon, the assistant attorney general of the Office of Justice Programs in the U.S. Department of Justice.

So far, the feds have dished out $100 million in grants and will allocate an additional $100 million by September.

“These are not our resources, these are your resources,” she told the conference. “Collectively, we can save lives and build safer communities.”

Community violence intervention programs embrace a nonpunitive way to prevent chronic gun violence. The programs work to interrupt the cycle of violence by working with people who are at highest risk through the provision of individually tailored support services, said Paul Carrillo, vice president of the Giffords Center for Violence Intervention.

Long studied and lauded by academics and activists as an alternative to law enforcement-focused responses, these programs are starting to get the attention of leaders from city, state and federal government, and money is beginning to flow into the programs.

The federal money available, however, is far less than the $5 billion that Biden proposed in 2021, following a 30% surge in homicides in 2020. But the president has told state and local leaders that they also can use American Rescue Plan money for community violence intervention programs.

Still, Carrillo, who grew up around gun violence in Southeast Los Angeles and started his career at a hospital-based violence intervention program, added a warning to activists and program leaders at the conference.

“As the old saying goes, when there’s more money there’s more problems,” he said.

The influx of federal dollars is an extraordinary opportunity for community groups to get much needed funding, said Connie Rice, a civil rights lawyer who helped reshape the Los Angeles Police Department through lawsuits and working within the department. She also created community safety partnerships that reduced the city’s violent crime rate over the past three decades.

But she cautioned that it is very difficult to distribute money effectively.

The work must be grounded in specific programs to address specific violence challenges in specific neighborhoods, or the programs will fail, she warned.

“When you have a lot of money, it’s like a gold rush,” said Rice, who co-founded the Urban Peace Institute. “You have got to do it in consultation and co-development with the groups that are most experienced and expert on the ground working.”

Those local groups, however, often don’t have the administrative capacity to apply for and dole out public dollars, she said; groups need intermediaries.

New money is also flowing in from cities and states. In 2017, five states invested $60 million in community violence intervention programs. By 2021, 15 states invested $700 million. Those programs and the funding continue to expand.

Last year, California announced $156 million in community intervention grants. Democratic lawmakers in the Golden State have also proposed legislation this year that would tax firearm sales to fund more community violence intervention programs. The bill passed the Assembly in May and is being considered in the state Senate.

Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass, who took office in December, will launch the Office of Community Safety to lead violence intervention initiatives to lower gun deaths through nonprofit partnerships.

The Los Angeles City Council heeded the mayor’s budget request to raise the starting salary for community intervention workers from $40,000 to $60,000 — a livable wage for people who have made communities safer for years, said Deputy Mayor Karren Lane, who heads the new office. But often, she argued, they have not gotten the credit they deserve.

“Homicides are down in Los Angeles because everyday people with lived experience, deep relationships in communities, put their lives on the line and disrupt violence,” she said. Indeed, after a spike in 2020, mirroring a national increase, homicides fell in 2022.?

Lane added, “While law enforcement may play a role, we also realize that once paramedics are called, police officers are called, emergency operating centers are established, we have already lost.”

An alternative to policing

The role of police in urban gun violence prevention has been contentious, especially as law enforcement agencies are funded substantially more than community-led programs. Many of the program leaders have been personally affected by police violence.

In March, police in New Jersey shot and killed Najee Seabrooks, a member of the Paterson Healing Collective. Seabrooks, whose job was to work with people who are at a high risk to commit or be the victim of gun violence, was having a mental health crisis when he was confronted by police at his home. He was wielding knives, according to police.

Members of the Paterson Healing Collective, trained in de-escalation and mediation, pleaded with police to allow them to talk to Seabrooks but were denied, despite Seabrooks asking for his colleagues’ help. He should be alive today, said Casey Melvin, the field operations manager for the organization.

“We’re still reeling from that,” he said.

Solomon, at the U.S. Department of Justice, asked the activists and program leaders gathered in Los Angeles last week how they can identify new opportunities for communities and police to “come together and leverage each other’s collective strengths.”

While she acknowledged that it was a “complicated ask in a complicated time,” she implored the room to realize they can’t do it alone.

This is an opportunity to show that community violence intervention can become even more effective, said Simpson, of Equal Justice USA.

Community violence intervention programs need multiyear funding from both private philanthropy and governments to create a sustainable infrastructure that lasts, he said. The current federal investment is a “drop in the bucket,” he said, and needs to increase consistently over time to reduce gun violence.

“We’re not just going to arrest our way out of this,” Simpson said.

Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott Greenberger for questions: [email protected]. Follow Stateline on Facebook and Twitter.?

]]>Corn grows at a farm in Belvidere, Ill. Many farmers throughout the Midwest are dealing with the fallout of a drought that has harmed corn and soybean growth. (Scott Olson/Getty Images)

City leaders in Storm Lake, a rural community of 11,000 in Northwest Iowa, are asking residents not to wash their cars or water their yards and gardens during the hottest part of the day. The city also has cut back on watering public recreational spaces, such as ballfields and golf courses.

These are highly unusual steps in a state that is normally flush with water and even prone to flooding. But the rain in Iowa, along with the rest of the Corn Belt states of the Midwest, has been mysteriously absent this spring, plunging the region into drought.

“It’s something new that residents have never had to really deal with before,” said Keri Navratil, the city manager of Storm Lake.

As California and much of the Western United States ease out of drought conditions after a spectacularly wet winter, the Midwest has fallen victim to a dry, hot spell that could have devastating consequences for the world’s food supply.

“America’s Breadbasket” — the vast corn, soy and wheat fields that extend from the Great Plains to Ohio — hasn’t had enough rain to sustain crop growth, which fuels a major part of the region’s economy, including food, animal feed and ethanol production. The region last suffered a substantial drought in 2012, and before that in 1988.

Though experts have not tied this event to climate change directly, scientists have warned that climate change will lead to more summer droughts for the Midwest in the years to come.

An unusually dry spring and summerlike heat have stunted crops, forced water conservation measures and lowered levels in major waterways, which could prevent barges from transporting goods downstream.

Missouri Republican Gov. Mike Parson has declared a drought alert to assist counties hurt by these dry conditions. City leaders in Oak Forest, Illinois; Wentzville, Missouri; and Lincoln, Nebraska, have called on residents to limit their water usage.

The region’s drought conditions are both unusual and concerning, said Dennis Todey, the director of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Midwest Climate Hub, which provides scientific analysis to the region’s agricultural and natural resource managers. This is the fourth year in a row of significant drought for much of the Midwest and Great Plains, he said.

“We’re reaching a point where we absolutely need to start getting rainfall over the main core of the Midwest,” he said. “We’re reaching a very concerning time here.”

This dry spell should not be happening, he added, especially with the return of El Ni?o, a cyclical weather event in which surface water temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean rise, causing wetter and warmer global weather. The Midwest is not getting that moisture.

Instead, a high-pressure system — which usually means sunny, calm weather — has parked itself above the region, preventing the precipitation needed for healthy crops and fully flowing waterways such as the Mississippi River. The frequent storms that are typical during the spring, fueled by moisture in the Gulf of Mexico, did not happen.

The majority of Iowa corn and soybean production is all rain-fed, and right now we just don’t have any.

– Mark Licht, Iowa State University associate professor and cropping systems specialist

Though “weird,” this weather pattern is not yet being connected to climate change, said Trent Ford, the Illinois state climatologist, who collects and analyzes the state’s climate data.

“It’s just extremely dry,” he said. “That’s why I said it’s weird. It is sort of this random weather pattern that’s established and has just really either persisted or I suppose evolved in a way to keep this part of the country very, very dry.”

Parts of Illinois have received only around 5% of normal rainfall this month, he added. Several places in the state should have 10 more inches of precipitation than they’ve gotten since April. Cities in the Chicago area are having their driest periods since 1936. Major rivers in the state, such as the Illinois and Kankakee, are at record lows for this time of year.

Nearly 60% of the Midwest, which includes Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio and Wisconsin, is under moderate drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, which is run jointly by the federal government and the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Nearly 93% of the region is abnormally dry, with around 16% of it suffering severe drought.

In the Great Plains states of Kansas and Nebraska, the situation is far worse. A quarter of Nebraska and 38% of Kansas are under extreme drought. More than a tenth of Nebraska and 8% of Kansas are in exceptional drought — the monitor’s most severe stage. The Great Plains has had drought conditions for more than a year, though it has received some rain in recent weeks.

The region’s drought couldn’t come at a worse time from an agricultural point of view, said Brad Rippey, a U.S. Department of Agriculture meteorologist and author of the U.S. Drought Monitor report. While?the arid conditions are?concerning, he said, there’s still time for the region to rebound.

“It’s still very young in the year, and if you look at drought intensity it’s not high yet,” he said. “Obviously, if it doesn’t rain over the next few weeks, that’s going to change. We’re really watching how this develops.”

These dry conditions have led to topsoil and subsoil moisture depletion, meaning less water in the ground to support planting and growing crops. Additionally, drier conditions have meant a vast browning of grasses and pasture lands, forcing farmers to buy more feed, instead of relying on grazing.

This is a critical time for farmers, as they approach the reproductive stage of crop development, when corn starts to silk and soybeans begin to blossom.

Mark Licht, an associate professor and cropping systems specialist at Iowa State University, recently walked the fields of a farm in Northeast Iowa that planted its soybeans after the early spring rains. Those soybeans didn’t have the moisture to germinate and emerge, he said, which has become a common problem throughout the state.

The state hasn’t had good rain since early May. What rain the state has gotten has been “spotty and patchy,” not providing enough precipitation to sustain the crops, he said. Soybean and corn plants are shorter than expected, with not enough canopy growth to protect the soil from weeds and sustained sunlight, which are harmful to crop development.

There is still some time for crops to rebound if the rain comes back. But if it doesn’t rain by the time the Iowa corn crop starts pollinating in a few weeks, its corn will have fewer kernels, which will raise prices for cattle owners who might have to look for alternative feed sources.

“We’re in a situation where we essentially need very timely rains to be able to get this crop through,” Licht said. “The majority of Iowa corn and soybean production is all rain-fed, and right now we just don’t have any.”