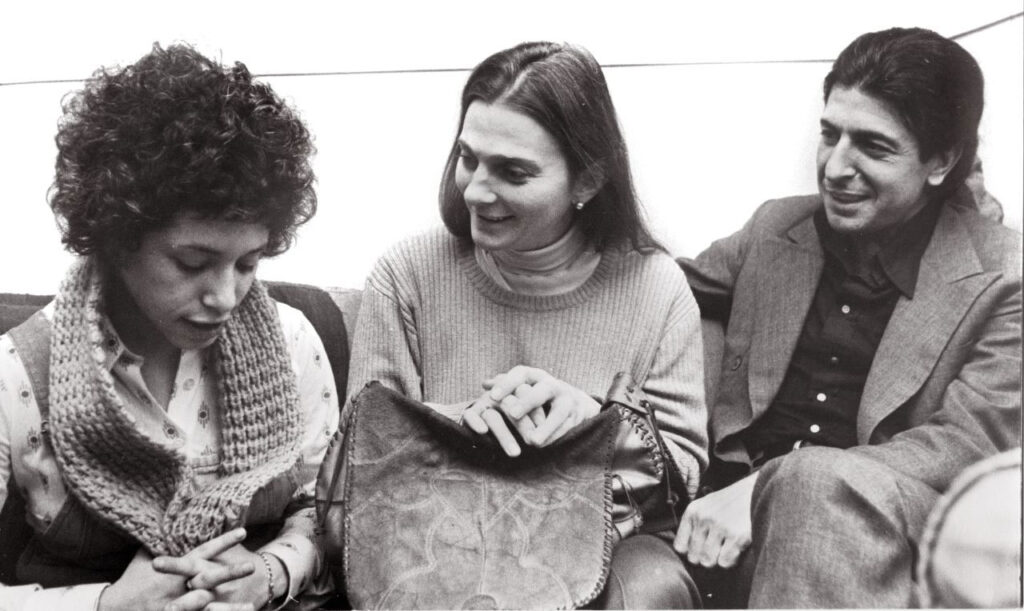

Multiple Grammy winner Janis Ian, left, in 2008 plays with the late Jean Ritchie, a Kentuckian who grew up in Viper in Perry County and after moving to New York became a celebrated artist in the folk music revival. (Photo courtesy of Janis Ian)

It was big news last year when singer-songwriter and multiple Grammy winner Janis Ian announced Berea College would be the home for her archives.?

Berea College archivists have been working with the collection since the first materials arrived and are now ready to share some of what they’ve cataloged. The college is celebrating the archives’ opening with a series of events Oct. 17-20.

Ian’s archives span over a century, beginning with her grandparents’ immigration papers early in the 20th century through Ian’s career performing around the world and with musical legends including Joan Baez, Leonard Berstein, Dolly Parton and many others, to her advocacy for civil, women’s and LGBTQ rights.?

Click here for information about the “Breaking Silence” celebration and a short video in which project archivist Peter Morphew offers an introduction to the collection.?

Some highlights of the weekend’s events:

Friday and Saturday, Oct. 18-19: During the day guests can see samples from the Ian archives in the Hutchins Library atrium as well as archival footage from Ian’s public addresses and concerts.

7 p.m. Friday, Oct. 18: The play “Mama’s Boy,” written by Ian’s mother, Pearl, will be performed at the Jelkeyl Drama Center.

7 p.m. Saturday, Oct. 19: Janis Ian Tribute Concert at Phelps Stokes Chapel emceed by Silas House will feature Amythyst Kiah, Aoife Scott, Melissa Carper, S.G Goodman, Senora May.

]]>One of Kentucky's largest employers, UPS operates what is described as the world's largest fully-automated package handling facility at its Worldport in Louisville. Ground crews unloaded loose parcels from the aft belly section of a Boeing 747 on Jan. 3, 2022. (Photo by Jon Cherry/Getty Images)

As the Kentucky General Assembly gathers in Frankfort, lawmakers will be looking for ways to lift Kentucky’s workforce participation rate, attract employers and usher in a more prosperous future.

They’ll likely consider tax policy, infrastructure subsidies and education’s role in growing an economy, making this a good time to look at the bigger economic picture. What are the industries that feed our families, pay our mortgages and our auto loans? What are the building blocks of a better, more prosperous Kentucky? And what can state government do to create that brighter future?

First, a few facts

- Kentucky’s economy accounts for about 1% of the GDP (gross domestic product) of the United States, meaning we are to some extent at the mercy of what happens in that other 99% of the national economy. “The Kentucky economy and Kentucky employment is really driven by what’s going on in the national market … and even the global economy,” explained Mike Clark, director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Kentucky’s Gatton College of Business and Economics.?

- One of the biggest contributors to the Kentucky budget is the federal government. As the annual report prepared by Clark’s center notes, pre-pandemic 27.8% of state and local revenue came from the feds (compared to a U.S. average of about 18.7%). That accelerated with federal aid during the pandemic to about 32.2 percent in 2020 (compared to a 21.3% national average.) Since then both the American Rescue Plan Act and the Infrastructure Act have directed even more federal money toward Kentucky.

- In November, 2023, the Kentucky nonfarm, civilian workforce was 2,036,638, of whom 87,245, or 4.3%, were unemployed. Like everywhere, employment in Kentucky largely revolves around the service economy, whether that’s providing medical care and education or food and lodging. The growth of service industry employment in Kentucky has been strong and steady in the last two decades, with short blips for recessions and the pandemic.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics - Kentucky has a higher percentage of people employed in manufacturing than most of the country, particularly in the auto and auto parts industries. The logistics industry, spurred by the presence of UPS, DHL, Amazon and FedEx is also a large and growing employer, driven in part by the explosion of online shopping during the pandemic, a trend that does not seem to have abated. “If you look at the four biggest employers in Kentucky, two of them are automakers, Ford and Toyota, and two of them are logistics, UPS and Amazon,” said Jason Bailey, executive director of the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy. Bourbon production, coal mining and horse racing and breeding, while very visible legacy sectors that in the case of horses and bourbon also drive tourism, are not significant drivers of the Kentucky economy.

State government employment has dropped by more than 25% in the last two decades. (Getty Images) - A sector where full time employment has declined is state government, dropping 27%, from 40,081 to 29,267, between 2002 and 2022, according to the state’s annual financial reports for the years 2022 and 2008. There are worker shortages across state government, including among K-12 teachers and bus drivers, social workers and public defenders. Every cabinet, from Tourism to Public Protection, has fewer employees than a decade ago.

- Kentucky continues to lag the nation in labor force participation, a measure of how many working-age people are working or looking for work. Kentucky’s rate hovers around 57% compared to closer to 63% for the nation. The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland analyzed factors contributing to low labor force participation. Generally, more people work in metropolitan areas and where wages are higher but they found that states, like Kentucky, with the lowest rates had older populations, lower educational attainment and higher disability rates.?

‘No magic bullet’

So, what’s a state government supposed to do to improve the economic life of a small state that still has a significant rural population and is at the mercy of national government spending as well as national and international economic trends?

There is “no magic bullet,” Clark said, but “if we can improve the overall level of education, that tends to improve our employment outcomes, our wages, our overall quality of life.”

An economist, Clark also said, “the market doesn’t seem to be providing child care,” throughout the state and at affordable rates which, he said, keeps some people, mostly young women, out of the labor force. Government subsidies of child care could provide benefits beyond those to the individuals involved. More fully employed, they would pay more taxes and be less likely to call on other government assistance, he said.??

“States have an impact on the long term trajectory by having an educated population, a modern infrastructure, good quality of life but in the short term they can’t change things rapidly,” Bailey said.

At this moment, Bailey and Clark agreed, unemployment is low and wages are relatively high in Kentucky. But, Bailey pointed out that Eastern Kentucky, “is not sharing in that prosperity,” and continues to lag in almost all indicators — employment, income, labor force participation, etc. He believes that the state should invest directly in the region rather than pursue “this idea that a (private industry) knight in shining armor is going to come and create jobs for all of us,” lured with state tax breaks or outright gifts. “A lot of hope and a lot of money were poured into things that led nowhere,” he said.

In the same vein, Bailey said the proposal to locate another federal prison in the region is ill-conceived, citing a report his center completed in 2023 that showed the other three federal prisons in Eastern Kentucky “haven’t moved the needle at all on the counties where they were located, they are still among the poorest in the country.”?

Instead, Bailey suggested, the federal government could spend the nearly $500 million the prison would cost, to “create jobs doing things people actually need, whether that’s reforestation, or youth leadership programs, or drug treatment or anything else.”?

Where the jobs are

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Kentucky Labor Force in November, 2023 was 2,036,600

That included:

- 444,600 people employed in the category listed as trade, transportation and utilities

- 307,800 in education and health services

- 232,900 in professional and business services

- 259,400 in manufacturing

- 307,900 in government

- 8,700 in mining and logging

Bourbon: The Kentucky Distillers Association in 2022 estimated that the industry accounted for “more than 22,500 jobs” and by 2025 will be “fueling more than 24,000 jobs”

Equine: The Kentucky Thoroughbred Association includes these numbers for direct jobs attributed to the equine industry: racing 24,402; equine competition 7,924; recreation 5,828.

The University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food and Environment reported 12,500 workers on Kentucky’s equine operations during 2022, comprising 6,300 full-time and 6,200 part-time employees

Coal: 4,804 were employed in mining, prep plants and office in the third quarter of 2023, according to the Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet’s Quarterly Coal Dashboard.

Despite the hazards that low head dams pose to humans and wildlife, fewer than a dozen of the 1,000-plus such structures in Kentucky have been removed in recent years, including a failing low head dam on the Barren River, above. (Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources)

In the early years of this nation and state, settlers built small dams on rivers and streams to capture waterpower for mills, enable navigation and assure a water supply. In the middle part of the last century even more were built as government agencies tried to bring waterways under control.

Today, thousands of those dams remain although new power sources and transportation methods, among other societal changes, have made most of them obsolete. Worse, almost all of them present a threat to humans and the aquatic environment.

In Kentucky alone, there are probably more than 1,000 of what are called low head dams — structures spanning a waterway that range in height from as little as one foot to about 15 feet.?

“In a lot of cases they’re not being used at all, nobody even knows who owns them, they’re just sitting there crumbling and they’re just a hazard” said Ward Wilson, a former executive director and board member of the Kentucky Waterways Alliance.

Like many historic structures, they can be scenic. There’s still water, like a pond, above the dam and, below, spillways that look like horizontal waterfalls. But, unlike aging courthouses and elegant mansions, low head dams disrupt aquatic species and degrade our environment. And they kill people.

“It doesn’t look like much, it doesn’t look like some raging rapid, but the way the water flows, it’s really hard to swim out of,” explained Wilson. “People are out there wading and they get caught and they die.”

That dangerous aquatic vortex is variously called a boil, backwash, danger zone or a drowning zone.?

A National Weather Service illustration dispassionately describes what it designates the “drowning zone” as “area of river in which only prompt, qualified rescue is likely to save a victim.”

And, just as there is no count of the number of dams themselves, there is no official database for dam-related deaths, either nationally or in Kentucky.

In Kentucky, there have been in the neighborhood of 40 fatalities documented in recent decades as kayakers, canoeists, tubers, swimmers and waders were sucked into their drowning zones. But Mike Hardin, assistant director of fisheries at the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources, says the death toll is much higher. “When you look up the history of some of these old dams … you will inevitably come across some old news story of somebody drowning. It is not new,” he said. As for the true total over the lifespan of the dams, he said, “I’d hate to think of what that number is.”

Water quality declines

Human deaths at low head dams are tragic and newsworthy. Less likely to capture headlines is the profound toll the dams take on aquatic species.?

“The rivers have a lot of functions and processes, such as moving sediment and gravel,” Hardin explained. “When the river flows it keeps those things clean swept, it keeps the water cool, it provides more complex habitat so that results in healthier fisheries, more diverse and rich species.”

But when rivers are interrupted by dams that all breaks down. “The long and short of it is, you’re basically creating a kind of semi-pond,” explained Lee Andrews, the field office supervisor in Kentucky for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service. “These structures that seem like pretty small, localized, man-made creations really have some wide-ranging effects.”

When water slows down or stands still, oxygen levels drop, the temperature rises and the sediment the water is carrying falls to the bottom, burying the gravel and stones on the stream floor, and the species that live there —? invertebrates like mussels and crayfish — in mud.?

In the loop that nature creates, declining water quality destroys mussels and a declining mussel population reduces water quality. While mussels are small, Andrews said, they are nonstop water purifiers. “That mussel is out there 24 hours a day, seven days a week, inhaling that water and filtering constantly. The more of them you have the cleaner your water is going to be.”?

Dirty water kills mussels and the fewer mussels, the dirtier the water.

And there are many fewer. Of the 103 species of mussels native to Kentucky, 20 are no longer found here and another 36 are considered endangered or threatened.

Damming streams also damages fish populations. Surveys have found the population of smallmouth bass “was 1,500% higher in free flowing water than it was in the impounded water,” Hardin said.?

In addition to higher temperatures and reduced food supply, dams also take a toll by isolating populations of the same species above and below the impoundment, which decreases the genetic diversity “that makes that species a little more resilient,” Andrews said.?

Plus, more species find homes in the stream when dams are removed. This summer, a year after a dam was removed on the Barren River, Andrews said, “we started finding some fairly rare fish were showing up on some of those habitats that were created.”

Beyond the individual streams and the species that occupy them, the entire watershed benefits, said Rich Cogen, president of the?Ohio River Foundation. Removing dams improves water quality in streams flowing into the Ohio, which American Rivers recently designated an?endangered river, and “since the water quality is better in those rivers then the water quality is improved in the Ohio River,”?Cogen said.

Removal is costly and complicated but cheaper than replacing a dam

The benefits are many but the number of low head dams removed is few, perhaps seven to 10 in total in Kentucky in the last several years. There are a lot of reasons for the slow pace. It can be costly, although never as expensive as replacing a failing or damaged dam. Sometimes it’s not even clear who owns a dam and obtaining all the permits — federal, state and sometimes local — required to remove a dam, can be a long and complicated process.

Cogen, who has been involved in several dam removals in Kentucky and Ohio, said there can also be concerns about water supply. “Land owners get nervous but really only people very close to the dam are going to see significant change,” he said. When a dam was removed near Owingsville a couple of years ago, a farmer upstream was worried about losing his water supply but the change “was imperceptible.”?

And, people don’t like change.?

When a dam has been in place for decades or centuries, the people who live nearby have a store of memories built around the way it has always been.?

Dam 6 on the Green River failed in 2017, becoming a hazard, and had to be removed, Andrews said, but it was a sad leave-taking. “We heard stories like ‘my grandpa taught me how to fish right here,’ ‘me and my girlfriend, now my wife of 55 years, used to come down here and picnic.’”

Andrews and others said that removing dams typically provides more opportunities, and safer ones, for recreation. Often, much of the debris from the dam is broken up and used to stabilize the banks, and the project includes creating a small park and new access to the water. Canoeists and kayakers no longer have to portage around the dams and people can play and swim safely in the free flowing water.?

Andrews’ message is simple: “If you know of one of these places don’t be afraid to allow somebody to take it out.”?

The benefits, he said, “spread all across society.”?

A healthier environment means more species thrive and fewer have to be listed as endangered which prompts regulatory intervention. But Andrews said that his agency doesn’t want to spend its time creating and enforcing regulations, it wants to save species. “We just want to have better habitat and more critters moving around out there for people to enjoy.”

Bass like free flowing water

The? Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources surveyed sport fisheries to compare free flow vs. impounded flow in the Barren and Green rivers and found notable differences based on habitat.

Barren River sport fishery

- Dominant species:

- The free flow section of the fishery is dominated by smallmouth bass, spotted bass and rock bass. These species reach quality and trophy sizes.

- The impounded sections fishery is dominated by largemouth bass, spotted bass and bluegill. These species on average do not reach the quality sizes that anglers prefer.

- Abundance of species:

- Black bass catch rates averaged 106% higher in free flow sections.

- Smallmouth bass, the more desirable stream black bass, catch rate averages 600% higher in the free flow sections.

- Rock bass catch rates average 3,731% higher in the free flow sections.

- Bluegill are the only sport fish species that is more prevalent in the impounded sections.?

- Overall, sport fish catch rates of all species combined was 51% higher in the free flow sections than the impounded sections.

Green River sport fishery

- Dominant species:

- Upstream of? Mammoth Cave National Park the free flow fishery is dominated by smallmouth bass, rock bass and channel catfish. These species reach quality and trophy sizes.

- Pool 5 (impounded) is dominated by spotted bass, largemouth bass and bluegill. These species on average do not reach the quality sizes that anglers preferof Black bass catch rates averaged 69% higher in the free flow sections.

2. ?Abundance of species:

- Smallmouth bass, the more desirable stream black bass, catch rates average 155% higher in the free flow sections.

- Rock bass catch rates average 2,600% higher in the free flow sections.

- Bluegill are the only sport fish species that is more prevalent in the impounded sections.

- Overall sport fish catch rates of all species combined was 114% higher in the free flow sections than the impounded sections.

This story has been corrected to show that Owingsville is the city near where a dam was removed. The city was incorrect in the earlier version. It also has been updated to clarify that Ward Wilson is a former member of the board of the Kentucky Waterways Alliance.

]]>From left, Rona Roberts, Councilman-At-Large James Brown and Barbara Sutherland stand on the site of what once was the racially integrated South Hill neighborhood, now the Rupp Arena parking lot. (Kentucky Lantern photo by Abbey Cutrer)

LEXINGTON — On Friday, May 17, 1907, the Lexington Leader ran an ad promoting a new subdivision. “Mentelle Park is the only perfectly appointed and finished residence park ever attempted in Lexington,” it proclaimed.?

The joys of the park were extolled: ?“model macadam roads … streets curbed with Bedford stone … splendid forest and shade trees on every lot.”?

And there were assurances the properties would not lose their value: “Every lot … of the same high class thus assuring the same high class of residents. … No nearby steam-railroads. … No negroes can ever own property or live in the park.”

This ad was uncovered by two women who set out to discover and document why Lexington housing is so segregated. The resulting website, Segregated Lexington, includes this ad and many more painful and much more current reminders of the enormous effort to create and reinforce segregated housing in Lexington that continued for decades after the development of Mentelle Park.

Barbara Sutherland and Rona Roberts document that virtually every institution connected to real estate — the federal and local governments, banks, developers and real estate agents — worked to restrict where Black people could buy and finance homes.

For example, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), created in 1934 to help the country and the building industry revive from the Great Depression, subsidized white suburbs with low down payments and affordable long-term mortgages. But the FHA enforced segregation by insisting the races not mix — a practice known as redlining — while imposing more stringent terms for people buying in the neighborhoods the FHA approved for Black residents.

Roberts and Sutherland figure that of 15,546 lots developed in Lexington from 1945 to 1961, Black families had access to only 225 lots, or 1.45%.

By the 1940s many new developments had restrictive covenants in property deeds that limited ownership to whites. Some were even included in deeds after 1948, when the Supreme Court rejected their legality.

After that court decision, racial segregation continued to be enforced through real estate agents, lending institutions, zoning and a variety of other structural and cultural avenues. For example, they found that in one 1960 edition of the Lexington Leader newspaper, Guyco real estate had one ad for “Wish House on Beautiful Fairway… that speaks of Southern Hospitality,” and another offering “Investment, Colored Property.”

The 1968 Federal Fair Housing Act outlawed steering — the practice of pointing homebuyers or renters toward or away from neighborhoods based on race — but a decade later a study by the Kentucky Commission on Human Rights found it was still prevalent.

People trained for the study, who differed in almost no way but by race, approached real estate agents and apartment complexes looking for a place to live. “At the rate of two out of every three cases, blacks and whites seeking homes or apartments in Fayette County were given racially discriminatory information about the availability, prices and requirements,” the KCHR reported.

In 1987, almost 20 years after steering was outlawed, the commission conducted a similar study. The rate of discrimination had dropped but remained at slightly over 38%. “It takes a long time for a law to become effective,” Roberts said.?

Time to level the playing field?

“I think their presentation makes it very clear that it has not been a level playing field,” said Urban County Council Member-at-Large James Brown, himself a real estate agent and one of the early supporters of Roberts’ and Sutherland’s work. And, he agrees, Lexington is still very segregated. Brown rejected the idea that people “self sort” based on cultural affinities. The source of the persistent segregation, he said, “is 80% economic.”

Americans have traditionally built wealth through their homes, often a family’s main asset. As homes appreciate, families are able to buy bigger, better houses, pay for college educations and help their kids, in turn, buy their own homes, continuing a cycle of generational wealth.

Brown has supported Lexington’s investment in recent years in an affordable housing trust fund that has invested almost exclusively in rental property. Now he said, he’s shifting his focus to “creating a wider path” to home ownership for historically underserved groups. “I think it not only helps stabilize families but it also helps stabilize neighborhoods.”

Brown foresees “a parallel affordable housing fund that’s targeted at home ownership,” with funding from the private sector. He’s had some conversations with financial institutions and others who might invest in it and is hopeful. “I think some folks are ready to put their money where their mouths are … helping to undo some of these historic wrongs.”

Another ally in the effort to address historic wrongs is the Bluegrass Realtors, led by CEO Justin Landon. “Many people think of this as ancient history and it’s just not,” he said, about the history of enforced segregation in housing. “The impacts of it are something we are very much still feeling today.”

There is no quick fix, he said. “It’s going to take a lot of work over a protracted period of time” to address the inequities baked into the system over more than a century. “Organizationally, we’re committed to doing that work.”

That’s starting in-house, he said, by making sure all their members see the material and understand their responsibilities both under the law and the Realtor code of ethics, which prohibits discrimination of any kind, not just in real estate transactions.?

His organization has approached the county clerk about helping to ferret out some of the restricted covenants in deeds to get them modified or removed. “They’re not enforceable but the reality is nobody should ever have to go in to buy their house and see that still sitting on their deed, right?”

Landon also believes his industry must work to diversify itself. “We need more Realtors, more mortgage lenders, more title professionals who come from the communities that don’t have as high home ownership rates,” he said. There are a few now, “and I could name them all,” which, he said, tells the whole story. The more real estate professionals from diverse communities “we can bring into the industry the more home ownership will seem like a natural, obtainable goal” for everyone, he said.

He agrees with Brown that there needs to be some kind of public-private partnership to help people whose families had been locked out of the market “begin the process of getting on that home ownership ladder,” whether that’s through down payment assistance or other services.?

But Landon thinks the search for solutions must go much further and deeper. “This did not happen by accident. This was public policy that was made by the government and reinforced by cultural issues,” he said, and it will take changes in public policy to find solutions.?

Noting that the Realtors are the largest trade association in America, Landon suggested some legislative changes the local chapter is likely to pursue in Frankfort, including homeowner savings accounts and tax credits for first time homebuyers.?

‘Unequal life opportunities’

In 2020, after the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, as the country seemed to, once again, unravel over racial tensions, Roberts and Sutherland,?self-described senior citizens who have known each other for decades, “turned toward the question of what responsibility white people like us bear for the horrors of systemic racism.”?

They decided to focus on Lexington and to investigate residential segregation. “We saw that race-based differences in Black and white home ownership result in unequal life opportunities that affect wealth, work, income, health, and education,” they wrote on the Segregated Lexington website.

And so they set out to research and document how residential segregation came about in Kentucky’s second-largest city and why it persists.

They have stayed away from suggesting “fixes,” deciding instead to remain focused on their research. “We can share this little body of information with other people but that doesn’t make me an expert in what to do about it, absolutely not,” Sutherland said.

Awareness, Landon said, is the first step in righting wrongs, finding solutions to difficult problems, and the two women took on the hard work of raising awareness. “It’s incredibly important work,” he said.

And hard. “It is always difficult to be the first person to speak up in a very public way about a topic that will make people uncomfortable.”?

One integrated neighborhood lost

For decades, there was at least one racially integrated neighborhood in Lexington.

The South Hill area had existed since at least the 1850s, and although it included blocks that were all-Black residents and all-white residents, since the 1930s there were blocks that were home to both Black and white residents.?

Then, in the 1970s, the Lexington Center Corporation was created to build Rupp Arena to provide a new home to the Kentucky Wildcat men’s basketball team right next door to South Hill. Since basketball fans would need a place to park, LCC turned its sights toward the “modest but livable homes in the three blocks closest to South Broadway,” to create a vast asphalt lot, according to Segregated Lexington.?

Although this was the era of urban renewal and slum clearing, the blocks were hardly slums. A 1971 planning commission study found that only 7.6% of the homes could be termed dilapidated.

Still, in November 1974 the Urban County Council backed LCC’s plan, setting off three years of protests, acrimonious public meetings, and lawsuits,” the authors, Barbara Sutherland and Rona Roberts, note. Ultimately, though, LCC won.

The result, they write, was that 580 residents of this small, stable, integrated neighborhood of modest homes, had to move.?

As Roberts and Sutherland sum it up, “the neighborhood was demolished, the residents were relocated, and Rupp Arena got its parking lot.”?

The first known advertisement by a slaveholder seeking return of an enslaved person in Kentucky was published in 1788, before statehood. (University of Kentucky Libraries)

LEXINGTON — Throughout the late spring of this year a group of nine University of Kentucky students did work that no one had ever done before.?

They scrolled through digital copies of early Kentucky newspapers, looking for advertisements seeking the return of people who had fled slavery, to record and preserve them.

“Ran away last spring, a man named Bartlett,” began one of the ads found in the Kentucky Gazette in 1803. “Uncommonly stout and broad across the shoulders, very dark complexion, his eyes sunk deep into his head, when spoken to generally puts on a smile but other times he has a thoughtful, ill look and possessing a great share of cunning acquiescence.”

Once owned by Colonel William Montgomery in Lincoln County, the ad said, he was sold to Henry Hall of Shelby County in 1801. The slaveholder trying to get him back lived in Natchez, Mississippi, and thought Bartlett might be trying to make his way “to Kentucky to his former place of residence.”?

The reward for returning this stout, cunning man was $100, close to $3,000 today.

Although the description of Bartlett is exceptionally detailed and the amount offered for his return is unusually large, advertising for the return of human property in early Kentucky was very ordinary.

“Each ad is probably the only record that exists for a whole person’s life,” said Caden Pearson, a history major, who recorded the ad for Bartlett.

In a matter of weeks the students found more than 700 ads that ranged from the vivid and specific like that for Bartlett to descriptions so generic it “almost makes you wonder if they even cared if they got the same person back,” Pearson said.

These ads, and thousands more that University of Kentucky research librarians and historians believe remain to be found in historic Kentucky newspapers will join the national digital archive Freedom on the Move.?

Based at Cornell University, Freedom on the Move’s goal is to create a database containing every runaway slave ad published in the United States from the Colonial Period until slavery was abolished in 1865 by the 13th Amendment.?

“It’s heartbreaking but it’s also inspiring,” said Vanessa Holden, the history professor at UK who formed the link with the national archive.

The descriptions often include scars from beatings, missing limbs, fingers and toes as well as evidence of sexual violence. “There are a lot of ads for young girls, 13, 14,” Holden said. “They’re described as beautiful, their hair is described, their stature is described, they’re described as attractive. And then you look to see who the enslaver is and it’s a guy who is significantly older.”?

But, horrible as it all is, she’s inspired by the fact that they left, even if they knew they would likely be recaptured. “It’s really empowering to learn stories of resistance. It’s really important to know that people fought back,” Holden said. “Can you imagine,” she said, in 1803 striking out alone as a runaway slave into the Kentucky wilderness? “We’re talking about people who are making these courageous leaps.”

Holden, an associate professor of history and African American and Africana studies and director of the Central Kentucky Slave Initiative, joined UK in 2017.?

That year ?she also became part of the group that was working to make the? idea of a digital registry into the reality it has become. By lucky coincidence, she arrived in Kentucky just as the project was getting underway and at UK, which has the biggest collection of historic newspapers in the state.

“Kentucky and Kentuckians are everywhere,” in the ads, Holden said. “Thanks very much to the slaving industry right here in Lexington, black Kentuckians are sold all over the American South,” she said. One of many misapprehensions the archive destroys is that enslaved people were only running to freedom. As was the case for Bartlett, “people looking for them often thought they might be heading back to Kentucky to be near family,” Holden said.

Not all the ads are placed by slave owners, there are also many from jailers — a very loose term that could include an actual public official but in many cases also meant just any white person who had a place to tie up people, often called slave jails or holding pens.??

Sometimes the people were being held while a slave trader accumulated enough people to make up a coffle to take South, sometimes it was a person who had run away and the ad hoc jailer was looking for a reward from the owner. If they weren’t claimed within a certain time the jailer could sell the person and keep the money.?

“It’s really crass to talk about human life in that way but you have to think in terms of movable property. The way large animals are treated legally is very close to slave law,” Holden explained. “They do treat people like runaway horses, or runaway livestock.”

But, as the ads illustrate clearly, the runaways were individuals with distinctive personalities and with families. Now the ads collected in a searchable database might help African American genealogists reconstruct those families that slavery tore apart.?

The archive “takes them so far beyond that 1870 wall,” explained Reinette Jones, reference librarian and researcher in UK Special Collections who is co-creator of the Notable Kentucky African-Americans Database.

To reach back into a family’s history, genealogists typically search census records for information about family groups, births, places of residence and the like. But before the 1870 census enslaved African Americans appeared only as property, perhaps with a first name or an age but often simply enumerated with other possessions. They didn’t appear as individual humans with full names and family groups until the first census after emancipation, in 1870.

Jones said this archive opens up additional information that people who want to break through that wall can use. Linking it with other sources, “you can go through and possibly piece together the genealogy.”

Freedom on the Move launched in 2018 with ads that had been collected for other research projects, bringing them into one database. But by last year it was beginning to look for other institutions around the country that could add to the collection.?

Jones was the person Holden reached out to as she sought a way to bring Kentucky and UK into the Freedom on the Move project. Soon, they assembled a meeting that included two others from UK Special Collections, Jennifer Bartlett, oral history librarian, and Kopana Terry, curator of the newspaper collection at UK.?

They met in August last year and by the fall began planning to bring in students to find the ads. The students began work in mid-March. This summer the team is working with Cornell to sort out any glitches in uploading the Kentucky information into the national database and expects the first Kentucky ads will go online in late July or early August.

It is Jennifer Bartlett who sorted out how to make the technical aspects of the project work. “We wanted to make it as easy as possible (for the students) to go in and concentrate on the papers themselves,” she said. In early newspapers the ads can be hard to find because they might just be words in type without images or anything else to separate them from other items on the pages. Sometimes, too, Jones said, the ad may start off being about a missing horse and it’s only farther down that you see a human ran away with the horse.?

Without getting deep into the technical aspects, because the ads are clipped in Photoshop, all the metadata associated with the ad — publication, date, page, column and how many slave ads are on the page — is automatically recorded along with a rough, searchable transcription. That means the ads can much more easily be searched for information that could add to the understanding of slavery in the United States — whether it’s by occupation (seamstress, groom, blacksmith, carpenter, etc.) or by former owners, or physical characteristics like scars or missing digits. The system is also designed to allow researchers to click through and see the entire page where an ad appears, providing context for that moment in time.

Using this system — which Bartlett hopes to be able to hand over to other institutions as they join the Freedom on the Move project —- the students had clipped over 700 ads by the end of the semester, barely nine months after the team first started planning. “This team worked together better than any team I’ve ever been on,” Jones said.

All of this means that when the effort started there were both newspapers to search and the technical know-how to make the findings available to the world. For Kopana Terry that means anyone going forward will be able to see the humans in the story that was slavery in the United States. She believes a vast collection of thousands upon thousands of runaway slave ads will have “far more impact” than reading one or two. “Imagine how humanizing it’s going to be to look at all those ads in a single database and realize that those are people, those are people,” she said. “You really get an insight into who these people were.”

The ads open a window on the people trying to break free, Holden agrees, but they also tell a story about the slaveholders and the society that tolerated, profited from slavery. “Enslavers knew how much enslaved people didn’t want to be slaves and that is pervasive. Resistance was pervasive, it was everywhere, all the time, and it was right there in the newspaper next to ads for corn and candles.”

Beyond the researchers who will learn more about slavery in this country, the team believes Freedom on the Move represents a tremendous resource for younger people. “It’s important for many of the students, especially in K through 12, to learn about slavery through resistance,” Holden said.

Jones welcomed the idea that in the current political environment using runaway slave ads as a teaching tool might meet with pushback.

“Let them push. This is part of the resistance,” she said. “Come on and push, help promote this project. I dare you to push.”

Thomas D. Clark: The gift that keeps on giving to Kentucky

There’s another story about historians, librarians and archives that has to be told to explain how the University of Kentucky’s involvement in Freedom on the Move could even happen.?

Without saved newspapers there would be nothing for the students to find, nothing for the digital readers to scan and record.?

That story goes back to the 1940s when Kentucky historian Thomas Clark began traveling around the state with a clunky thing that looked like a suitcase but opened up to display a camera with lights on either side. Working with librarians, he visited local newspapers and set up shop to photograph their archives, creating microfilm for the UK archive.?

Although the quality was not so great, with the images fading out toward the sides because the lights didn’t really reach the edges, that early and admirable effort set the scene for UK’s newspaper collection.

Eventually, the National Endowment for the Humanities spearheaded an effort to inventory newspaper holdings across the country, called the United States Newspaper Program, which operated for almost 30 years, beginning in 1981. Instead of traveling the state with a suitcase setup, newspaper archives came to UK. Kopana Terry at UK Special Collections said they reached out to longstanding Kentucky newspapers to get their historic records. “We brought them in, we microfilmed them, we sent them back out,” she said.

By this century, the effort had shifted to digitizing newspapers and UK was one of the first six institutions to be awarded a grant under the National Digital Newspaper Program, and the only one to do all the work in-house.?

That allowed UK to help refine the standards for digitizing newspapers, Terry said, and create a training program, called meta/morphosis, that is still used around the country and the world to teach people how to transfer from film to digital storage.

When librarians and archivists do the work of saving records they don’t know, can’t know all the uses they will serve. It’s unlikely that Clark envisioned Freedom on the Move when he was driving around with his suitcase setup. But, 70 years later his work is helping unearth the lives of people whose names were never even put in a census.

Newspapers are often called the first draft of history but Reinette Jones, Terry’s colleague at Special Collections, thinks they are more than that: “For many people it’s the only draft.”

This story has been updated to correct a misattribution.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Janis Ian grew up in New Jersey, a long way from the Kentucky knobs where an abolitionist minister founded Berea College in 1855. (Photo by Melissa Falen, courtesy of Janis Ian)

BEREA — On one of their visits, Janis Ian took Berea College President Lyle Roelofs to her studio. There he saw a photo of “a very young” Ian sitting at a grand piano. “Looking over her shoulder at the music she had written and was playing from,” he realized, was Leonard Bernstein, the legendary songwriter and longtime conductor of the New York Philharmonic.

Roelofs was visiting Ian to assure her that Berea would be a good home for her archives, which chronicle more than five decades of her work and life as a singer, songwriter, activist and winner of two Grammy Awards.

?The material in the collection, Roelofs said, “will just totally blow you away.”

For Ian, it’s a “win-win” because her vast personal collection has found a place where it will be not only safe and cared for but appreciated and used.?

As she and her wife, Pat Snyder, started looking for a home for the collection, Ian said they spoke with many major institutions and some “fairly substantial amounts of money” were thrown around.?

But many had so much in their collections that Ian’s things would spend most of their time in storage. For example, the Smithsonian Institution said it would be at least a decade before any of Ian’s material could be exhibited. Ian appreciated the frankness but also “realized that all of the major institutions would face the same problem.”

And then there was also the quirkiness of the collection, she said. “Who wants the archives of a songwriter, it’s not like that’s an important thing, right?”?

Ian’s friendships and correspondence embrace a wide range of people — Dolly Parton, Stella Adler, Willie Nelson, Mel Torme, Chick Corea, Lily Tomlin. There’s a book of poetry, her mother’s plays, a Grammy not only for best female pop performance (“At Seventeen” in 1975) but for best spoken word (“Society’s Child: My Autobiography” in? 2012), there’s her father’s — later her — guitar and the sheets where she composed her songs.

“Most archivists have been trained to deal in paper” Ian said, “and if it’s a Hollywood star like Katherine Hepburn, costumes, but not an artist like me.”

Ian grew up in New Jersey, a long way from the Kentucky knobs where an abolitionist minister founded Berea College in 1855. Her career took her to Los Angeles and around the world as a performer before she settled in Nashville.?

Berea never hit her radar until she and Snyder created the Pearl Foundation around 2000 to honor Ian’s mother, who had always dreamed of going to college but wasn’t able to until her successful daughter sent her. Through the foundation they wanted to help other people realize their dream of an education.?

She said her friend, songwriter Billy Edd Wheeler, told her “’look, if you’re going to be giving money away in scholarships you ought to be giving it to Berea,”’ where he had graduated in 1955. Plus, Snyder had a former student who had gone there and was “just raving about how great it was.”??

“We visited Berea once and we were as impressed as we expected to be,” she said, so they established an endowment to provide scholarships there but left it to the school to administer, remaining very hands-off.

Years later as they worked their way through the major institutions looking for a home for her archives they found, “there was always some reason that it wasn’t right.” And then they began to consider Berea again.?

For a small school Berea has a pretty significant archive that now includes the collections of author and activist bell hooks and Appalachian folk singer Jean Ritchie, “who I admire greatly,” Ian said.

Plus, there was Berea’s mission. It was the first integrated, co-educational college in the South and hasn’t charged tuition since 1892. “I really like the dichotomy,” Ian said. “Berea is not a Jewish school, not a particularly gay school, not a lot of the things that I am … and yet, it is.”

Like many Berea students, Ian said, “I started out on a farm. My earliest memories are of singing to the chickens from the back of a flatbed truck.” And her family worked hard to create a place for themselves in this world, like those of many Berea students. “My grandparents were immigrants, I always felt out of place, I’m self-educated, my dad was the first person in either family to graduate from college.” So, for all the differences, “there’s a lot of commonality.”

And then there was the fact that Berea invests in its students. Ian said Snyder summed it up: “All of these schools have $15 million stadiums and then there’s the school that has the $15 million students, which do you want to be aligned with?” In the end, “it was pretty much a no-brainer.”

Ian had lunch with Teresa Kash Davis, a Berea grad herself who is now the school’s vice president for alumni and philanthropy. After lunch, Ian recalled, she said, “so, why don’t I just leave Berea my archives, let’s just do that.” Davis “just kind of looked at me with her mouth hanging open and said ‘well, we can’t pay you.’” And that was fine.?

Roelofs and others made trips to Florida — where Ian and Snyder now live — to assure them the collection would get the attention it deserves. Over the course of 18 months they worked out details about how the material would be transferred, Berea’s financial commitment to the care and display of the collection and other arrangements, including Ian’s commitment to

helping raise money to support Berea’s work with the collection. “Janis is a very thoughtful person who makes sure she gets all the details right,” he said.

He sees that attention to detail in her work. The archives will offer Berea students who aspire to careers in music to see the “real discipline of songwriting,” Roelofs said. Every word in her songs, he said, has been “intentionally and carefully chosen.” It was an education for him. “I’m not a songwriter, I’m a theoretical physicist,” Roelofs said, but going through some of Ian’s papers has “deepened my appreciation of songwriting and the seriousness of that as an artistic pursuit.”?

For archivist Peter Morphew the lode of songbooks, diaries, family documents and personal memorabilia that Janis Ian has donated to Berea College can be summed up in one phrase: “It’s her life.”

It is Morphew’s job to examine, record and catalog every item in the 167 boxes that have already arrived at Berea. They include her letters and diaries, the sheets on which she wrote her songs with extensive notations (“Her handwriting is so beautiful. I am so thankful,” Morphew said) as well as memorabilia like hats and boots she wore on stage, photographs, drawings, comic books, posters, and the guitar she’s played since she was a child.

The collection also includes records of the inner workings of a career as a performer — travel documents, business records, contracts, correspondence with producers and managers, promoters and fans.

And it includes the files Ian obtained that the FBI kept on her parents, the children of Eastern European Jewish immigrants who were active in liberal causes.

“It took me 13 years and my mother died before she could see hers. It took the intervention of several lawyers but we did finally get what they say are the complete files,” she said. “It’s kind of hard to look at them through all that black Magic Marker,” used to obscure the identities of informants although, “we knew who most of the informers were, it’s a small world.”

Through decades of activism herself Ian has learned some lessons. In the ’60s, “my generation gravely underestimated the lengths to which people would go to stay in power. We didn’t understand that for a lot of people, power was more important than their families, than their grandchildren, than their dignity.”?

Still, she said, there’s been enormous progress. “As a gay person I can no longer be institutionalized for being gay, not legally, anyway. As a Jew I can’t be denied the right to hold office or to join a club. … And we don’t assume that just because you win, you get to enslave the other country, and that was the norm until very, very recently. So I have to believe that we have moved forward.”

But there are still fights to fight. “It’s discouraging when you see certain people who have a clear lack of respect for women and yet they’re still in power. It’s discouraging when you see women supporting those men, it’s very discouraging.”

Ian said she recently received a lifetime award from the Folk Alliance and used some of the two minutes allotted for her speech to tell her peers it’s still important to use art to speak up. “Be brave,” she said, “and if you can’t be brave, because we all get scared, pretend to be brave because if you pretend long enough you’ll end up being brave.”

A guitar too good to forget

There are many stories in the papers and objects Janis Ian has given to Berea College but none can match the odyssey of her 1937 Martin D-18 serial #67053.

Ian’s father bought the guitar for $25 in 1948 from the widow of a farmer who’d had it in the attic for years. Ian, born three years later, grew up with it, wrote her first songs on it, and learned from it. In a column about their relationship, ?she wrote: “The guitar you grow up with, the guitar you learn to play on, is a special thing. It doesn’t matter much whether it’s expensive, pretty, even playable — it trains you.”?

When she was 16, her father gave it to her. She and the guitar had earned each other: “By then we’d met Leonard Bernstein, recorded 2 albums, been on The Tonight Show and done concerts from coast to coast. We’d lived through Society’s Child together, getting spit on and booed off the stage by crowds chanting ‘Nigger lover!’”

The Martin D-18 had her (Ian had assigned it a feminine identity along the way) own following, she wrote. “Artists like Jimi Hendrix would greet me and say “How’s The Guitar doing, man? What a sweetheart!’…. It was an extraordinary instrument, a 1937 D-18 that somehow, through a combination of wood, break-in, temperature, humidity, and just plain love, wound up being the best acoustic guitar any of them had ever seen.”

And then it was stolen.?

One day Ian returned to her apartment in Los Angeles, where she’d moved in 1972, to find both the Martin and another guitar gone. She reported the theft to the police, called every pawn shop in L.A., offered a reward and eventually recovered the second guitar, a Gallagher, but the Martin was lost to her.

“Nothing in my life — not breakups, not the death of beloved friends and family, not the loss of every dime I had in 1986 — nothing affected me more deeply,” Ian wrote. She never forgot the guitar and never gave up hope of seeing her again. Each album she released included this notice: “Missing since 1972, Martin D-18 serial #67053. Reward for return; no questions asked.”?

The decades went by and she didn’t return. Then, 26 years after the Martin was stolen, Janis Ian opened up her email one day to see “RE: Your D-18.”?

It was from the owner of a guitar shop in Tiburon, California who had a client who said he had Ian’s guitar. Did she want his number?

She did and she called. The man had bought the guitar in 1972 for $650. It had also been stolen from him, in 1976, but recovered. He dealt regularly in instruments, he told her, but held on to her guitar because “it’s the best D-18 I’ve ever heard.” He’d seen an article about her in Vintage Guitar Magazine in which she mentioned she was still looking for her guitar. “It took me 15 seconds to realize that was my Martin you were looking for,” he told her.

They reached an agreement on a trade for another vintage Martin she owned and the guitar her father had bought in 1948 and given to her in 1967 finally came home. She wondered if it would be the beautiful instrument she remembered or had she “spent the last 26 years mourning nothing more than an imaginary ideal.”

But when she hit a chord “it rang forever. I pressed my ear against her side to hear the aftertones, the subtones, all the little nuances I remembered. Everything was there. Everything was stunning. Everything was beautiful.”

A volunteer battles Lonicera maackii or bush honeysuckle at Floracliff Nature Sanctuary in southern Fayette County. (Photo courtesy of Floracliff Nature Sanctuary)

From late fall to early spring, volunteers fan out across Kentucky woodlands to battle an aggressive invader they know they can’t defeat but hope to hold at bay: Lonicera maackii aka Amur honeysuckle aka?bush honeysuckle.

They pull it, dig it, spray it and cut it (then spray again) in an effort to protect ecosystems that have nurtured plants, insects and animals for millenia.

The Lantern could find no estimates of how many tens of thousands of acres of Kentucky woodlands — not to mention pastures and highway rights of way — are in peril because of bush honeysuckle.

?A?small study in 2011 gives some idea of the magnitude of the challenge. At Locust Grove National Historic Landmark in Jefferson County, students surveyed at 60 points in 27.5 forested acres, finding about 31,000 honeysuckle plants.

“The days of being able to not do anything are past us,” said Ellen Crocker, who teaches at the University of Kentucky’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources.?

A benign-seeming honeysuckle can start in a fence row or roadside then move on to “wreak havoc” in natural areas, she said. Once established it can outcompete native plants and help starve native animal species of the nourishment they need to survive and thrive.?

How did this happen?

Like almost all invasive species, bush honeysuckle — the most common species in Kentucky is Amur honeysuckle or Lonicera maackii — came from somewhere else, in this case the region where China and Korea meet. Also, as often but not always happens, it was invited here, arriving as an ornamental planting in the late 19th century. And like kudzu and some other invasives, it was promoted for conservation use because, well, it’s good at covering bare ground quickly.

Too good. Once honeysuckle gains a toehold in an area, “if you don’t do anything it will be a honeysuckle field,” Crocker said.?

Bush honeysuckle, like most invasive species, has particular qualities that allow it to “out-compete” native species. It can thrive in many soils and produces a vast number of seeds — as many as a million on a mature, 20-foot tall plant per season — which birds eat (more on that later) and then distribute through their droppings.?

Plus, it is allelopathic, meaning the roots emit a chemical that can hinder growth in other, native plants. (Some native species, like the black walnut, also use this characteristic to their advantage.)

?And, it leafs out earlier in the spring and stays green later in the fall than most native species, meaning it claims an early share of sun and water that plants need to emerge.

This last characteristic, though, is one that foresters, natural land managers and homeowners can use to their advantage in fighting bush honeysuckle. As the only green plant in the landscape early and late, honeysuckle is easy to spot. Small plants can easily be pulled up, especially if the soil is damp, while larger ones might require a tool to get the roots out of the soil.?

Large plants can be cut down and then the stump treated with herbicide to prevent re-sprouting. For huge infestations, herbicide sprays can be effective when honeysuckle is the only green thing around and the poison is less likely to damage other, dormant plants.

This all sounds time-consuming and expensive, and it is. That’s why natural areas often rely heavily on volunteers to manage invasive species.?

At Floracliff Nature Sanctuary in southeastern Fayette County “volunteers come out once a week almost every week of the year working on invasive species,” said Josie Miller, the stewardship director there.?

Annually, volunteers put in about 3,000 hours at Floracliff. They do other things, like guide hikes and work on trails, but a large portion of that time is spent on fighting invasive species. “It would be a huge barrier if we were doing this with paid staff,” Miller said.

Given that it’s impossible to remove all the honeysuckle and other invasive species and keep them out, land managers like Miller have to make choices. At Floracliff the choice is to focus on the areas that have the most native species to help them survive and thrive. That’s typically the ravines, which were never farmed and were lightly disturbed for logging, if at all. In those areas native trees can drop seeds and some of them will sprout to become replacement trees, if they aren’t crowded out by honeysuckle.

Promoting a diverse forest of native species isn’t just an academic or aesthetic preference. All species use sun, soil and water to grow and produce food that other species consume, and so on through the food chain.?

Honeysuckle berries “are like junk food,” Miller explained, high in carbs but low in the fats — provided by native species like viburnum and dogwood — that birds need to survive the winter. Plus, they “can cause diarrhea in birds.”?

But it goes beyond that. “Insects convert plants to food for birds,” Miller explained. Honeysuckle “is not much of a host plant to caterpillars and insects” whereas an oak tree hosts 400 to 500 different varieties of caterpillars, providing lots of protein for birds in the spring when they need it.?

Vigilance advised

So, when an invasive species like honeysuckle gains hold of an area it begins a downward cascade that affects the entire ecosystem and can potentially disrupt it for decades.

Research at Northern Kentucky University has recently found that bush honeysuckle can endanger stream health because its leaves decompose rapidly, sucking up oxygen in the water that aquatic species need to survive.

When the invasives are dominant “our native communities are no longer functioning well,” Miller said.

This is what Jessica Slade found in the woods at the University of Kentucky Arboretum when she became the Native Plants Collection manager and curator there last year.?

The 15 acres of woodland in a corner of the Arboretum is a remnant of forests once found throughout the Bluegrass. Some trees there are as much as 300 years old but the woods had become “pretty degraded” through the onslaught of invasive species, including honeysuckle and winter creeper, an evergreen groundcover that can climb up tree trunks and is still sold in many nurseries.?

“You could spend all of your time on” trying to eradicate them, she said. At the Arboretum, like Floracliff, volunteers “are pretty passionate about” removing the invasive species and know them very, very well.?Slade and Miller quickly ticked off a list of invasive species, some of which are still being planted along highways, around shopping malls and in private yards: Lesser Celadine, Miscanthus, Porcelain berry, Autumn Olive, privet, Johnson grass, garlic mustard, callery or Bradford pear, Tree of Heaven, Burning Bush. “They all have different strategies that make them more successful,” Slade said.

What to do? “Be vigilant,” recommended Billy Thomas, an Extension Forester with the UK Department of Forestry.?

Learn to identify the invasive species and pull them up before they get big enough to spread elsewhere. There are resources to help people who own larger tracts of land — most forest in Kentucky is in private hands — manage the expense of controlling invasive species. He said that, rather than try to eradicate them from an entire tract, “just pick an area” and work to control non-native species there.?

But, all the experts said, it’s important to recognize that it’s an ongoing thing. Invasive species spread through bird droppings, on the wind, through the water and in other ways so they will always return.?

If nothing else, Thomas said, just take it as “a great excuse to get out into your woods, scouting for invasives.”

Happy hunting.?

Joseph Monroe, holding his son Angus, raises grass-fed calves in Henry County and markets them through Our Home Place Meat. Photo courtesy of The Berry Center

NEW CASTLE?— For more than a century Henry County relied on tobacco to keep its farmers and its economy going.

For most of the second half of the 20th century a federal program?stabilized the price of tobacco, guaranteeing those farmers a steady, predictable income. That all changed in the new century after Congress ended tobacco price supports.

Just as all that change was underway, Mary Berry, the daughter of Henry County’s?renowned author, activist, farmer and environmentalist Wendell Berry, founded The?Berry Center to carry on his vision of “prosperous well-tended farms serving and supporting healthy local communities.”

Thinking about how to help farmers prosper, they began with the mantra, “start with what?you have.” With tobacco gone, what Henry County had was cattle and pasture.

No state east of the Mississippi River produces more cattle than Kentucky.

So the Berry Center began to think about ways small farmers could make more, and more?predictable, money from their cattle operations and landed on the idea of producing veal.

Rose veal is so natural. You don’t feed mama cows grain, they just live on the farm and eat grass,” and the calves aren’t given antibiotics, steroids or hormones.

– Bob Perry, chef and teacher

The economics made sense. Typically, weaned calves would be sent off in a tractor-trailer to a feedlot in the Midwest, fattened up and then sold into the industrial meat?complex. Cutting out all the middlemen and harvesting them at weaning for a premium?product could mean more money going directly to the farmer.

And that’s how Our Home Place Meat came to be in 2017. A pilot program created and?supported by the nonprofit Berry Center, Our Home Place took on the challenge of?persuading farmers to raise the veal, guaranteeing them a price for it, and finding markets?for it.

It was a tall order.

The program began with the principle of guaranteeing a price that took into account farmers’ expenses and added a reasonable profit. “With the market you are gambling,” explained Beth Douglas, who directs the program. “At the beginning of the year we tell the farmers how many cattle we will purchase and at what price. That allows the farmers to plan for the year.”

Plus, the farmers don’t have to invest in different equipment or new barns, they just have?to keep raising cattle and, instead of sending them off to feed lots, “we take it to?Trackside Butcher Shoppe,” in Campbellsburg (also in Henry County), Douglas said. “So?it’s literally not changing anything for the farmer. It’s taking them where they are.”

At the same time, Our Home Place began developing partnerships for marketing the?product.

Overcoming veal’s bad rep

Veal had fallen out of the favor in the United States because of inhumane methods —?confining calves in small pens to prevent muscle development, feeding them only milk or?milk solids — used to produce a very white, tender meat.

But in Europe veal is different, a?rosy-colored meat from calves raised outside, nursing and eating grass. This was the type?of veal they wanted to raise in Henry County.

Perry helped with the re-education process by preparing a multi-course meal at The Berry?Center in 2017 using Rose Veal, inviting chefs to taste the product. He cooked sliders,?ribeyes, strips and filets, even veal blanc which he described as “the national French?hangover food” to demonstrate the flavor and versatility of Rose Veal.

But even if chefs wanted it they had to be able to get it. That’s where What Chefs Want!?(formerly Creation Gardens), a Louisville-based wholesaler came into the venture.

John Thomas, a vice-president there, said it is a partnership, not a typical?customer-vendor relationship. His team works with the farmers, Douglas and the people?at Trackside Butcher Shoppe, discussing pricing, production and quality.

“Everybody’s really on the same page and pulling in the same direction,” Thomas said.

That gives What Chefs Want! what it needs to promote Rose Veal to restaurateurs who want to source more of their food locally and support family farmers.

“There’s plenty of beef out there to buy, we didn’t need another beef supplier. We needed a relationship that has a purpose.”

And, he adds, “we’re very, very happy with the product.”

At Red Hog Artisan Meat in Louisville most of the meat comes from whole animals that?are processed in-house by a team of five butchers. But Aaron Sortman, the executive?butcher there, jumped at the chance to get involved when he learned what the Berry?Center was doing “to help out these smaller farms.” He’d always admired Wendell?Berry’s work (“I think he’s the coolest”) and is constantly on the lookout for “local farms?that ethically raise their animals.”

Although Red Hog butchers most of its own meat, they need to fill in the gaps for many?popular items like tenderloins, New York strip steaks and ribeyes, and Our Home Place?has “become our main supplemental supplier.” Sortman buys both Rose Veal and?Berry Beef, meat from older cattle that are finished on grain but on the farm in pastures?not in feedlots.

‘Better product from a taste standpoint’

As with Thomas at What Chefs Want!, Sortman said there’s a personal relationship that?he’d never get with a commodity producer. He met several of the farmers at a dinner?sponsored by Our Home Place and has sent some of his butchers to workshops to learn?more about the product.

As far as he’s concerned, it’s a safer product (less chance of bacterial contamination from?large farms and factory feedlots) and “an alternative to the supermarket food chain.”

Plus, Sortman said, “it’s a better product from a taste standpoint.”

Most new ventures fail because they must make money from day one, explained Douglas,?but the Berry Center’s support has “given us time to build the program and figure out?what works and what doesn’t work.”

Last year the program handled about 100 head and returned $245,000 to the Henry?County economy through direct payments to farmers and to Trackside for processing the?meat. This year Douglas figures that the combination of Rose Veal and Berry Beef will reach about 270 head.

Those aren’t big figures in the sea of the Kentucky agriculture economy but they make a?difference to local farmers, said John Logan Brent, the retiring Henry County judge?executive, a member of The Berry Center board and a farmer who sells to the program —?about 20 head of veal and 10 of beef this year. He figures the contract with Our Home?Place typically adds from $200 to $300 a head to the commodity price. For small?operations that extra income is “something they can count on, (it) certainly makes a?difference at the end of the year.”

Brent sees a future when this pilot program can grow up and become a full-fledged?agricultural cooperative that can pay its own administrative costs but believes it will?have to achieve a scale of about 1,000 head processed annually to get there.

Our Home Place targets young farmers, Brent said, many of whom “desperately want to?be involved in agriculture,” whether they are trying to make a family farm work or are new?to the business. An added benefit of this program is that it gives them a product they can?be proud of. “Who thanks you for your animals at a sale barn?”

]]>