19:22

News Story

10,000 Kentuckians marched to demand racial equality. My grandmother was one of them.

Freedom March 60th anniversary to be commemorated Tuesday in Frankfort

I never got a chance to ask my grandmother about what March 5, 1964 was like for her. What she heard from speakers on the steps of the Kentucky Capitol. If she saw Martin Luther King Jr. or Jackie Robinson. What she felt standing with thousands of others from across Kentucky.

She didn’t speak much about that day when I was growing up and? visiting her Ohio home outside Cincinnati. I had never seen the photo until I found it online in 2021, and by that point Alzheimer’s disease had eroded her memories. Virginia Niemeyer died last year at 88.

But I do know she walked out the door of her Lakeside Park, Kentucky, home to board a chartered bus at 8 a.m., one of at least 300 people who traveled from Boone, Campbell and Kenton counties to hear King urge state leaders to pass a civil rights law. My grandmother Virginia was just one of 10,000 who gathered from across Kentucky that day for what became known as the Freedom March on Frankfort.?

I know she boarded that bus, paying a $3 round-trip fare, because the Cincinnati Enquirer published a picture of her the day after the march. She sat in an aisle seat, her gloved hand holding a protest sign. The story in my family was that my grandfather didn’t find out she had gone to Frankfort until she appeared in the paper the next day.

We often hear about the powerful words of the Rev. King, rightfully so. But there were plenty of Kentuckians who had been fighting for civil rights in their communities and organizing to make sure the March on Frankfort happened. Lacking? my grandmother’s account, I wanted a glimpse of that day through the eyes of others who were there and who made the day possible.?

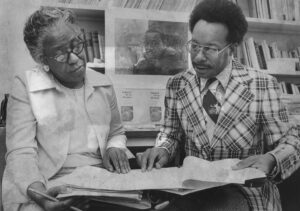

Pictured on that bus with my grandmother, standing in the middle aisle, was the Rev. Edgar Mack, the executive secretary of? the Northern Kentucky branch of the NAACP and the pastor of St. Paul A.M.E. Church in Newport in 1964. Mack, who grew up in Shelbyville the son of a sharecropper, helped make sure Northern Kentucky was represented that day.?

“My dad was a true believer,” Rodney Mack, the son of Edgar, told me in a recent interview. “He believed in people, he believed in the movement, he believed that this was right, and he just wasn’t going to be quiet about it.”

Civil rights activists in Northern Kentucky had been working before the march to confront segregation and other racist laws and norms in Covington. Black women including Alice Shimfessel and Bertha Moore were integral to the protests and efforts desegregating public accommodations in Northern Kentucky even before a state civil rights law was passed, according to the Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky.

In the weeks leading up to the March on Frankfort, Rev. Edgar Mack was an ever-present name in newspapers as he spread the word to Northern Kentuckians about the march. According to newspaper articles, faith leaders met at a Covington YMCA a week before to discuss the march, with a rally organized at a local church “to generate enthusiasm” the weekend before.?

“The march shall be dignified, peaceful and prayerful,” Rev. Mack told the Kentucky Post and Times-Star in February 1964. “It will demonstrate our concern that the state Legislature pass the urgently needed civil rights bill for Kentucky.”?

The march achieved all of that, according to the accounts of people who were there, although it would be two years before a civil rights bill became state law. Sharyn Mitchell, who was a teenager from Berea when she joined the march, said she had “never seen so many Black people in my whole life.”

“Because from Capital Avenue, from the bridge, straight up to the Capitol, was wall-to-wall. I’m talking about up on the porches and then in the yards — wall-to-wall Black people,” Mitchell told historian Le Datta Denise Grimes, who was conducting an oral history project on the march that’s archived at the University of Kentucky.?

Freedom March on Frankfort gallery (Click on photos)

Freedom March, from left to right, Rev. Olof Anderson, Syod Executive of the Presbyterian Church, Louisville, 13-year-old Sherman McAlpin, Louisville, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Rev. Wyatt Walker, executive-secretary of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Dr. D.E. King, pastor of Zion Baptist Church, Louisville, and Frank Stanley Jr., chief editor of The Louisville Defender, March 5, 1964. ( Public Information Collection, Archives and Records Management Division, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives)

In the weeks after the march, 32 hunger strikers spent 104 hours in the Kentucky Capitol House chamber to try to convince legislators to pass the Civil Rights bill. March 16-20, 1964 (Public Information Collection, Archives and Records Management Division, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives)

Mitchell also remembered singing on the bus from Berea to Frankfort and at the state Capitol, a “groundswell of ‘We Shall Overcome.’”?

Sheila Burton, who was a high school student in Frankfort in 1964, remembered Rev. Edgar Mack as one of the civil rights leaders active in Frankfort in the 1960s. Mack had previously served as the president of the Frankfort NAACP before becoming a pastor in Newport.?

Burton had left her high school during lunch break to see the speakers, she told Grimes for the oral history project, inching her way up through the crowd.?

“I just remember being in the midst of the crowd and feeling like, you know, ‘I’m there. I was there.’ That I can say I was there,” Burton said in 2021. “I just wanted to say I was there.”

Jessica Knox, the daughter of Northern Kentucky civil rights leader Fermon Knox, who worked alongside Mack, remembered her father putting in weeks of organizing and work. He traveled to Lexington, Louisville and other parts of the state encouraging people to join the march.??

On March 5, white women came out of their homes on Main Street in Frankfort to offer marchers cups of water; another neighbor offered marchers the use of a bathroom, Knox told Grimes as a part of the oral history project,

“They were so sweet. And it was something we were not expecting at all,” Knox said. “[I]t made me realize that there are such beautiful people in this world.”

Inclusion of people — no matter who they were —? was central for Edgar Mack, according to his son Rodney. “He would find like-minded people — and he didn’t care where they came from,” Rodney Mack told me.?

While the large majority of the crowd were Black Kentuckians, according to newspaper accounts, allies also showed up in solidarity, including my grandmother. Virginia was a nurse at the former Booth Hospital in Covington, where Rodney Mack’s mother and Edgar Mack’s wife Lillie Mae Mack was also a nurse. It’s unclear if Lillie and Virginia had worked together at the time, as my grandmother left her job when she began to raise my father and aunt at home in the 1960s.?

While my grandparents, father and aunt moved to Ohio the same month as the march, in Kentucky the work of civil rights and racial equality continued. In 1966, Kentucky Gov. Edward Breathitt signed into law the first state civil rights legislation south of the Mason-Dixon line. Nonetheless, Rodney Mack said his father still had to file lawsuits to make sure he? and his siblings were afforded equal rights under that law.?

Rodney Mack said his father would refer to the March on Frankfort in church services as a “critical stepping stone” on the way to future challenges and progress. Rev. Edgar Mack moved on to be employed as a social worker traveling throughout Eastern Kentucky and eventually become a professor of social work at the University of Kentucky. He later moved to Nashville to take a position with the A.M.E. Church, and he died in Tennessee in 1991.?

“I don’t think he thought that it was ever over,” Rodney Mack told me. “There was always another ‘first’ that needed to happen to break ground for more than inclusion.”?

Rodney went to the March on Frankfort as an 8-year-old with his sisters, his mother driving a car because the chartered buses were full.?

When I asked him what his father would think of today’s political climate, he asked me to put myself in my grandmother’s shoes.

“Would you take your kids? Or go yourself on something like that these days? I don’t know that you would,” Rodney Mack said, saying that the fear of violence and other backlash is real.

“In some ways I’d like to be able to talk to my dad, tell him what’s going on,” Mack said. “I know, he’d just be shaking his head.”

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.

Liam Niemeyer

Liam covers government and policy in Kentucky and its impacts throughout the Commonwealth for the Kentucky Lantern. He most recently spent four years reporting award-winning stories for WKMS Public Radio in Murray.

Kentucky Lantern is part of States Newsroom, the nation’s largest state-focused nonprofit news organization.