5:50

News Story

Kentucky’s population shifted older in a decade. Here’s how and why it matters.

Homeownership down too, while gaps by race widen

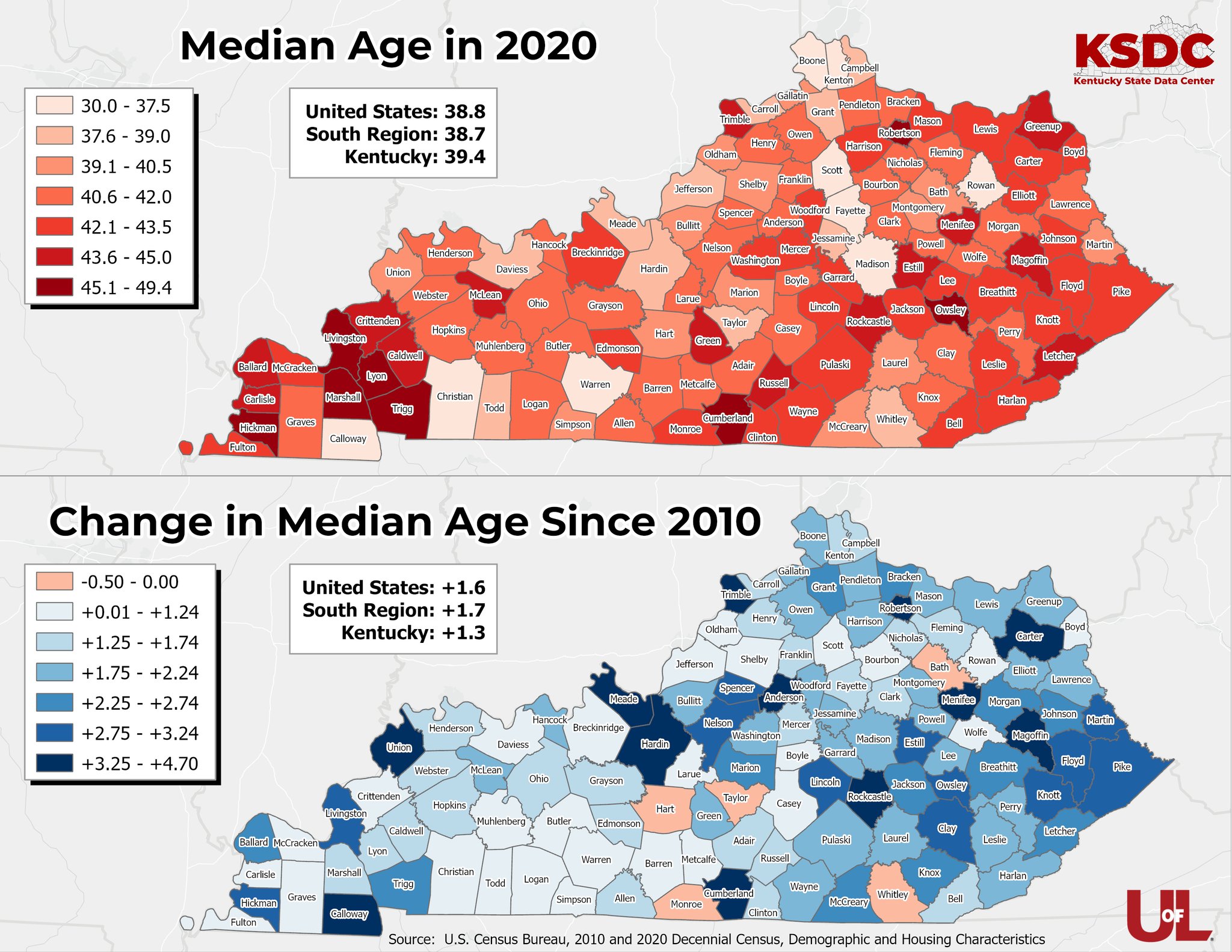

Kentucky’s population is shifting older, new data shows, with the oldest counties in the western part of the state.?

Counties with colleges and military clusters are home to the younger populations, according to analyses of new Census data by the Kentucky State Data Center (KSDC).

Eastern Kentucky is aging faster than the rest of the state, according to KSDC, which could be because of young people moving away.?

Between 2010 and 2020, the median Kentuckian age increased from 38.1 to 39.4. The population ages 65 and older also increased from 13.3% to 17%.?

An aging population — and fewer babies

“It’s not unexpected that the population is aging like this,” said Matthew H. Ruther, the KSDC director and a University of Louisville professor.?

However, the increase from 13% to 17% is “a really big jump,” he said. “And it’s not done yet. We’re going to still be seeing this going into the future.”?

In fact, Ruther estimates the 65 and older population will hit 20%.??

“The peak of the baby boom was in 1957,” he explained. “Those people are now 66. And so you’re … still going to be seeing this older population get larger, both in absolute terms and as a percent of the population.”?

With that increase, the state will need to consider the medical needs of the older population and the demands that will be placed on the health care system. The National Library of Medicine in 2008 reported that chronic conditions are more prevalent in older communities, producing greater utilization of health care services.?

The National Council on Aging said in March that about 95% of older adults have at least one chronic condition, such as diabetes and heart disease. Almost 80% have two or more chronic conditions, according to the Center on Aging.?

Yet large areas of Kentucky suffer from a lack of primary care providers.? The Kentucky Primary Care Association said in 2022 that 94% of the state’s 120 counties don’t have enough primary care providers.?

“People are already having trouble getting to doctors or hospitals because of supply issues,” Ruther said. “If nothing changed, then this is going to become more problematic in the future.”?

And while the older age group widens, some younger groups are smaller. That means fewer people are preparing to enter the workforce than are getting ready to leave it.?

We see fewer young people, in part, because people are delaying starting a family, Ruther said.?

Deaths exceeded births in 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, when there were nearly 4,000 more deaths than births in Kentucky. In 2021, deaths exceeded births by 8,089, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The trend is continuing. Preliminary data shows that in 2022 Kentucky deaths (57,269) exceeded births (52,458) by about 4,800.

The CDC said that in 2021, the mean age of American mothers at the time of their first birth was 27.3 years. That’s up from 27.1 in 2020.?

“People wait longer to have children,” Ruther said. “And then when people wait, they tend not to achieve their intended fertility.”?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says that “peak reproductive years” are between the late teens and late 20s.?

“By age 30, fertility (the ability to get pregnant) starts to decline,” ACOG says. “This decline happens faster once you reach your mid-30s. By 45, fertility has declined so much that getting pregnant naturally is unlikely.”?

These birth declines are “also not unexpected,” Ruther said. “But there are definitely going to be some ramifications for school systems across the state,” such as lower enrollments.?

Homeownership disparities — by race

Meanwhile, the percent of Kentuckians who own homes declined from 2010 to 2029.

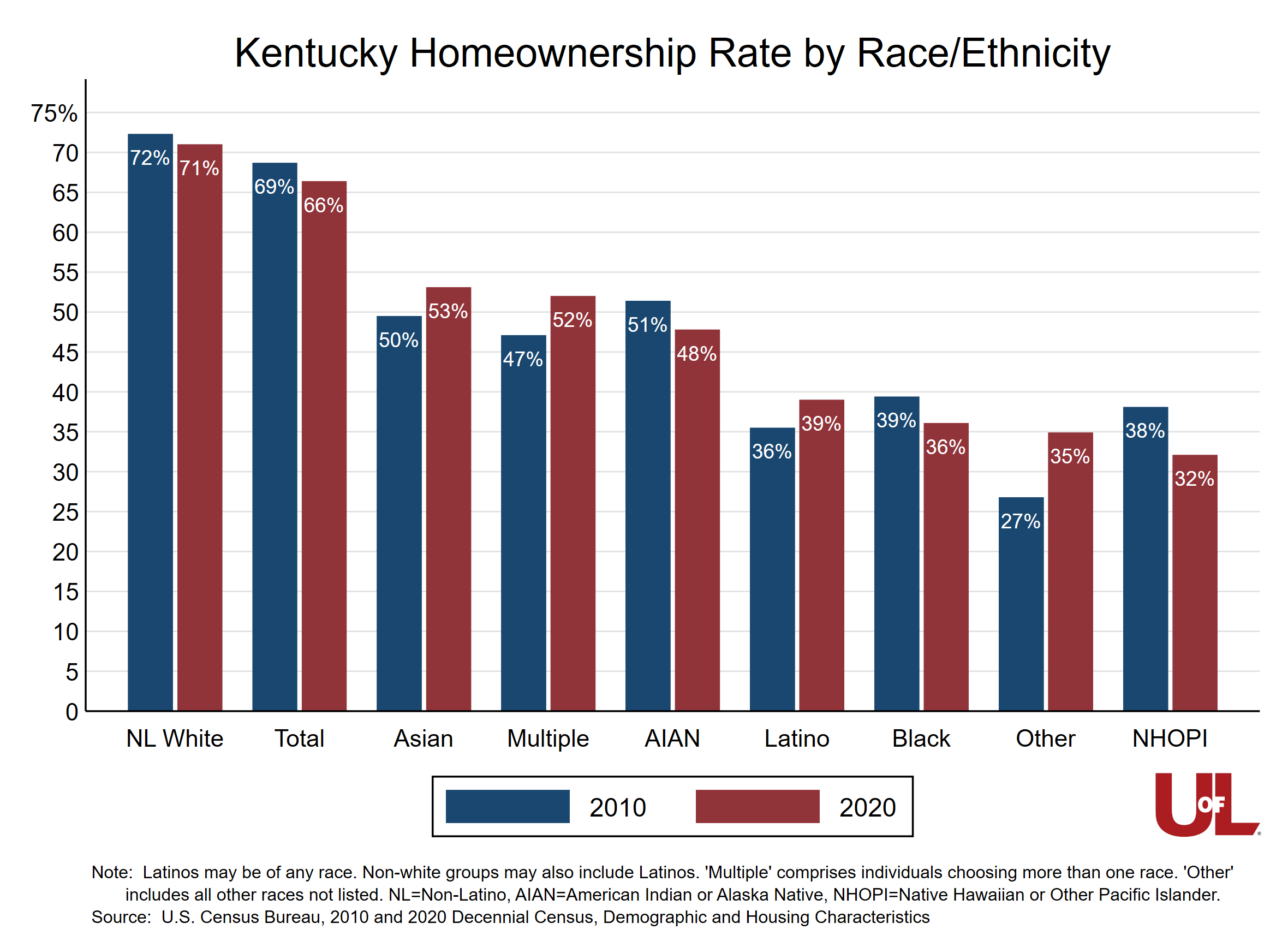

Between 2010 and 2020, homeownership in Kentucky declined overall from 69% to 66%. Factors may include the price of buying a house rising faster than wages and not enough access to credit, according to the KSDC.?

Beyond the general decline, there exist disparities between white and Black homeowners, Ruther said.?

Homeownership for white Kentuckians dropped from 72% to 71% over the decade, while for Black Kentuckians it fell from 39% to 36%.?

“Homeownership isn’t the end-all be-all of life, right?” Ruther said. “Some people don’t want to own a home. There’s … nothing necessarily wrong with that. But it is the primary way that people — that households — build wealth.”?

“Wealth-building opportunities are limited when you are renting,” he added. “So that’s … going to reverberate into the future.”?

A change in single households?

Kentucky is also seeing an increase in single-person households.?

“When we think of single-person households, most people tend to think of young people living carefree on their own,” Ruther said. “But a lot of the single-person households are actually … older individuals who are widowed or never married.”?

Especially in the western and eastern parts of the state, single-person households tend to be older people, Ruther said. Single-person households in urban areas like Lexington or Louisville are younger people, often college students living in apartments.?

“It’s sort of new that people are living by themselves,” Ruther said. “I don’t think that the number of single-person households outnumbers the number of two-parent family households, but it’s probably very close at this point.”?

COVID-19, floods and tornadoes

This data only covers up to 2020, so much isn’t represented, such as the full effect of COVID-19, as well as the housing and migration issues brought on by the deadly tornadoes in West Kentucky and the back-to-back floods in the East.?

The demographic fallout over these events, Ruther said, should show up in the next few data releases.?

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.

Sarah Ladd

Sarah Ladd is a Louisville-based journalist from West Kentucky who's covered everything from crime to higher education. She spent nearly two years on the metro breaking news desk at The Courier Journal. In 2020, she started reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic and has covered health ever since. As the Kentucky Lantern's health reporter, she focuses on mental health, LGBTQ+ issues, children's welfare, COVID-19 and more.

Kentucky Lantern is part of States Newsroom, the nation’s largest state-focused nonprofit news organization.