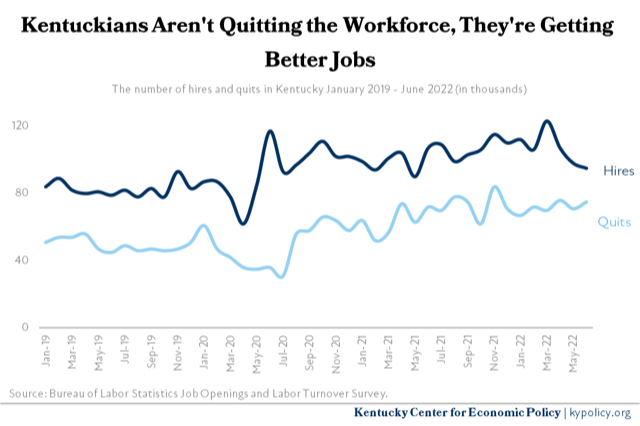

Since the pandemic recovery began in May 2020, there have been 40,000 more hires than quits every month on average in Kentucky. Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

Why must someone laid off from a job be further penalized by the state? To be denied long-established unemployment benefits? To be pressured to take an available job rather than find one that advanced a career?

Yet Kentucky lawmakers decided the state must become a harsh taskmaster, snapping a whip to get people back into the workforce quickly, as if they are simply widgets to fill any hole.

Even in a year of high inflation and a possible recession. Even knowing that rural areas offer limited job opportunities. And outright ignoring that those who qualify for unemployment are workers — not those who choose to live on government aid.

The current policy, pegged to a three-month unemployment rate, has cut the duration of benefits from 26 weeks to 12 weeks. Job seekers must accept “suitable” jobs within 30 miles of home — even if the pay is low and it doesn’t fit work experience.

Gov. Andy Beshear rightly labeled as “cruel” these changes pushed by conservative think tanks and businesses that pay the benefits. Kentucky is one of six states curtailing a program created during the 1930s Great Depression.

Barriers to benefits only force people onto government rolls and longer periods of joblessness, according to the nonpartisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Unemployment — at its lowest level in more than 50 years — is not holding back job growth. “Recent research illustrates that slashing unemployment benefits will not significantly boost employment, despite rhetoric to the contrary,” the center said.

Such shortsightedness reflects a growing disrespect for the working class, which only erodes citizen support of government. Hostility is apparent in authoritarian philosophies pushed by the wealthy, failed trickle-down economics embraced by politicians, and a Christian nationalism labeling others evil.

Kentucky lawmakers have elevated corporate interests over workers; given themselves an 8% raise while denying teachers a 5% increase during a teacher shortage; and prioritized tax cuts, rather than needed services, in spending surpluses created by federal pandemic aid.

Jonathan Miller, former Kentucky Finance and Administration secretary and author of a book on community values, put it succinctly: “It’s a scary time. People are looking for other people to blame. It’s leading to results that hurt working people, people who have been pigeonholed and denigrated.”

Business leaders and some lawmakers insist unemployment cutbacks are needed because Kentucky has half the workers needed for open positions. The Kentucky Chamber of Commerce, for example, is wisely working to help former inmates move directly into jobs.

But those currently in the workforce also face challenges: remote work, staff cutbacks, mass firings by email, and increased use of automation and artificial intelligence.

Workers are engaged in “a great reshuffling,” according to a 2022 report by the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy. The state’s older population is leaving full-time work; those in low-paying jobs are looking for better ones. Since the pandemic recovery began in May 2020, there have been 40,000 more hires than quits every month on average, the report said.

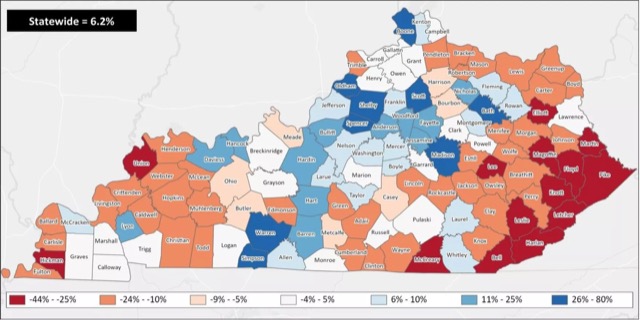

Worker shortage could also result from Kentucky’s .01 percent population growth from 2020 to 2022, based on Census data. The Kentucky State Data Center at the University of Louisville is predicting only a 6.2 percent population increase by 2050, mostly from growth in Fayette, Warren, Jefferson, Boone and Scott counties.

Not enough people are relocating here. Kentucky’s appeal is undermined by such realities as 22 percent of our children live in poverty and the state has the fifth-lowest life expectancy rate. Changes are needed to improve the quality of life. For example, raising the minimum wage would improve the lives of hundreds of thousands — mostly women with children — and put more money into the economy.

Kentucky’s minimum wage is set at the federal rate of $7.25 an hour, which has not changed for 13 years. A full-time worker earns $15,080 a year — $9,780 less than the federal poverty rate for a family of three. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that 4.4% of Kentucky workers earn minimum wage — nearly twice the national rate of 2.3 percent.

Twenty states raised wages this year either through legislatures, ballot measures or earlier planned increases. Eight states have approved plans for a $15 minimum.

Lawmakers could at least allow growing urban area to increase wages. In 2016, the Kentucky Supreme Court ruled that increases by Lexington and Louisville violated state law. Allowing exceptions in the law and monitoring the impact would be reasonable step by the legislature.

Addressing obstacles to building a robust workforce won’t be easy. But it must rise beyond faulty assumptions and quick fixes that penalize people unfortunate enough to lose a job in an uncertain economy.

“We’re a religious state,” said Miller. “And I wish we could fulfill those religious values, with compassion for those who need it the most.”