Kentucky's Constitution endorses slavery for one group of citizens: inmates. (Getty Images)

This column, ?first published by the Kentucky Lantern earlier this month, inspired Marc Murphy’s political art that we are publishing on the holiday honoring?asassinated?civil rights hero the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Kentucky resisted the end of slavery, refusing to certify the 13th Amendment at the time and only freeing people six months after June 19, 1865, the day celebrated as the Juneteenth holiday. Legislators finally ratified the amendment in 1976.

And to this day, the state Constitution endorses slavery for one group of citizens: inmates. Reads Section 25: “Slavery?and involuntary servitude in this State are forbidden, except as a punishment for crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”

Kentuckians should follow the lead of Alabama, Tennessee, Vermont and Oregon which voted Nov. 8 to remove similar language from their constitutions. The votes have not ended prison labor but have raised discussions about work mandates and low pay.

Such reassessment could benefit Kentucky, which has backtracked on once-touted criminal-justice reform. Urgently in need of workers, government and business leaders recently announced plans to move ex-inmates quickly into jobs. How people are treated while incarcerated could influence the success of those efforts.

The slavery exception was written into the U.S. Constitution as former slave states sought to retain a flow of cheap labor. New laws, called the?Black Codes, criminalized vagrancy, unpaid fees and even bad language to keep prisons and jails full of workers who could be leased out.

A congressional bill, the Abolition Amendment, aims to close the loophole. If approved, it must be ratified by three-fourths of the states. Said Oregon Sen. Jeff Merkley, a bill sponsor: “The loophole in our constitution’s ban on slavery not only allowed slavery to continue but launched an era of discrimination and mass incarceration that continues to this day.”

It angered Terrance A. Sullivan, executive director of the Kentucky Commission on Human Rights, to realize Kentucky is among the minority of states that retain the slavery exception. He is lobbying legislators for a ballot measure to change it.

“I want people to be as mad as I am that it exists,” he said in a column in the Courier-Journal. “I want people to call, text, tweet, email or whatever they prefer to their elected officials to help me make sure this time next year that this section is amended, and slavery can forever be in the past in Kentucky.”

Kentucky was once hailed for 2011 legislation aimed at reducing incarceration. Ten years later, analysis by the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy showed it had failed. If Kentucky were a country, its 30,000 inmates would rank it as the seventh highest incarceration rate in the world, the report concluded.

In that decade, lawmakers passed 59 bills that enhanced felony penalties, especially for drug offenses. They passed 10 bills that reduced criminalization. Instead of the projected $422 million savings from fewer imprisonments, the state’s corrections budget increased 72 percent. We spent more to lock people up than to engage youth, mitigate poverty and develop job skills.

Kentucky puts inmates to work within prisons and in the community. The standard pay is $1.56 for an eight-hour workday; 78 cents for those getting credit for time served, according to the Department of Corrections. Kentucky Correctional Industries operates in 15 industries – including warehousing, manufacturing, textiles, printing, and furniture making. About 600 inmates worked in 2021 in eight prisons and four farm operations.

Also, during the last fiscal year, 3,109 low-risk state inmates in county jails worked at local recycling centers and animal shelters, performed roadside cleanup, and collected garbage. Their labor, compared to paying others minimum wage, saved the counties about $34 million, according to the department’s annual report.

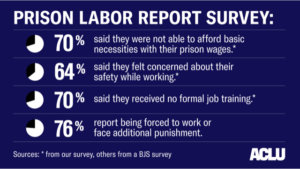

Low wages generate feelings of exploitation, according to the American Civil Liberties Union’s June report?on prison labor. Governments take up to 80 percent of wages for room and board, court costs, restitution and other fees. Also, prisons charge high costs for necessities like phone calls, hygiene products and medical care.

The ACLU argues that inmates should get state minimum wages and fewer deductions. “They should be properly trained for the work they perform,” the report concluded, “and we should be investing in programs that provide incarcerated workers with marketable skills.”

About 13,100 state inmates are released annually; most have problems finding full-time work with benefits. The majority of inmates are age 40 or younger, serving 10 years or less for property crimes.

The Beshear administration and the Kentucky Chamber of Commerce announced a Prison-to-Work Pipeline ?that would match jobs with inmates leaving all 13 prisons and 19 local jails that house state inmates. “The goal is for reentering inmates to have a job offer and be ready to start to work the day they walk out the gate,” Justice and Public Safety Secretary Kerry Harvey said during the November announcement.

Kentucky has 160,000 open jobs but fewer than 80,000 people actively pursuing careers, said chamber president and CEO Ashli Watts. “Not only are we able to connect individuals in need of employment with employers looking for candidates, but we are able to connect individuals in industries where they have prior experience and skills,” she said.

This effort holds promise, although it is also urgent that the legislature reevaluate its “tough on crime” posture that leads to building more prisons and packing inmates in county jails.

Some may dismiss concern about the slavery exception as nothing more than symbolism. But it is easier to rebuild lives – and the workforce – if the state is not also sending the message that some citizens are only worthy of indentured servitude.

]]>